During my time as CEO of the China-Australia Chamber of Commerce in Beijing from 2013 until July this year, I had a ringside seat to the rapid rise and subsequent deterioration in bilateral relations between China and Australia. The reasons for the deterioration were complex, with fault on both sides, and we must learn from them or risk history repeating.

From 2013 to 2015, barely a week went by without a senior federal minister, premier, chief minister or CEO coming through Beijing or another major city to engage with local Australian businesses while visiting a highly receptive Chinese government.

The 2014 G20 in Brisbane was a triumph. Xi Jinping became the first Chinese president to address parliament and I vividly recall the first Australia Week in China in April 2014. The positivity, dynamism and genuine goodwill regarding Australia’s special relationship with China was demonstrated by Tony Abbott’s presence and the joint efforts on behalf of both governments in the search for answers after MH370 had disappeared weeks earlier, tragically claiming the lives of 152 Chinese citizens and six Australians.

Both former prime minister Scott Morrison and current PM Anthony Albanese have made the point that it isn’t Australia that has changed, it’s China. They are right, China has changed under Xi Jinping. This was clear to anyone living in or engaging closely with China.

Australia needed to deal with China as it is, not as it wished it would be. A common mistake in international relations.

Many of the policy positions put forward that offended Xi Jinping’s China were more than reasonable in isolation. Sadly, however, the manner in which they were communicated and their cumulative effect was deeply damaging to the bilateral relationship. This could and should have been avoided.

Former foreign affairs minister Marise Payne demonstrated how not to conduct diplomacy on ABC’s Insiders program in April 2020 when, to the apparent surprise of everyone, she called for an independent investigation into the origins of Covid-19.

Unsurprisingly, no meaningful international support for this proposal was forthcoming. Other nations were busy dealing with their own problems. And to top it off, we failed to notify our Chinese friends of this proposal, one that was certain to infuriate.

When you are about to deeply offend your largest trading partner, it is polite to at least let them know in advance.

Precisely what was achieved?

Our barley growers lost their lucrative Chinese market, wine exports went from A$1.1bn to $25m and a host of other exports were negatively impacted by Australia being the least favoured nation on the planet among Chinese customs officials.

Additionally, even if there were no direct tariffs on certain goods, buyers diversified elsewhere because of the perceived elevated risk when buying Australian-made.

Of course China has not stopped buying barley, wine, beef and many other commodities that were negatively impacted. Instead it is buying them from the US, New Zealand, Canada, the EU, Latin America and other nations and regions that Australians would rightly regard as friends, and in some cases close allies.

If you need evidence, key to the US-China phase one trade deal signed in January 2020 was China committing to purchase an additional US$32bn worth of agricultural products from the US in 2020 and 2021. Beef and other commodities from our close ally the US surged, to the detriment of Australian farmers and exporters.

Could one really expect that any US president, especially one seeking re-election, would help Australia farmers when politically crucial agriculture-producing states are benefiting from our folly? As Paul Keating’s mentor Jack Lang was fond of saying: “Always back self-interest – at least you know it’s trying.”

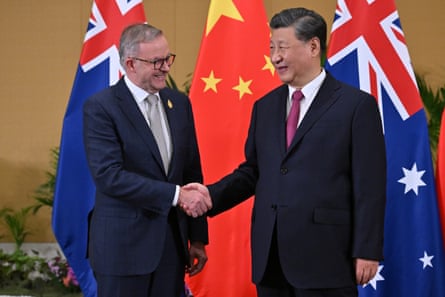

So how do we fix a problem like China? Albanese and the foreign affairs minister, Penny Wong, are making a strong start by letting others lead when criticism is warranted and by showing maximum restraint. Restraint is not a display of weakness, but maturity. From personal experience, I know how difficult that is.

Bilateral meetings have been constructive and the Coalition seem to be learning in opposition led by Simon Birmingham as shadow minister for foreign affairs.

Australia must be proactive, persistent and make clear to China that a stable, mutually beneficial relationship is in the national interest of both parties. That we will be taking a more nuanced approach and refrain from joining the pile–on with Washington at every opportunity.

China includes into its calculations Australia’s strong security alliance with the US; it always has. There is no need to talk it up every five minutes as Morrison seemed to do.

How the UK, Canada, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand communicate when in the middle of a US-China dispute is instructive.

The Penny Wong approach – cooperate where we can and disagree when we must – is far more constructive than the Morrison/Payne approach: cooperate where we must and disagree when we can.

The 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations on 21 December represents an opportunity for both sides to make meaningful progress on repairing relations. Wong heading to Beijing to seize this opportunity is the right call and will hopefully be followed by a visit from the prime minister early next year.

The trade issues can be solved as quickly as they were put in place. However, it is likely there will be steps along the road to a full normalisation of trade and investment flows.

Start with the symbolic then move to the practical.

One symbolic option could be to mark the occasion via a joint reaffirmation of the original 1972 communique. To reflect on the great achievements and commit to another 50 years of cooperation based on “the principles of mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful co-existence”.

Urge China to respond in kind with a gesture of goodwill. For example, I happen to know this lovely, talented Australian journalist who would really like to see her two kids, mum, dad and some bloke she happened to think was worth hanging around with for reasons unknown.

Lastly, keep referring to the relationship as a “comprehensive strategic partnership” because that is precisely what it should be.