Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

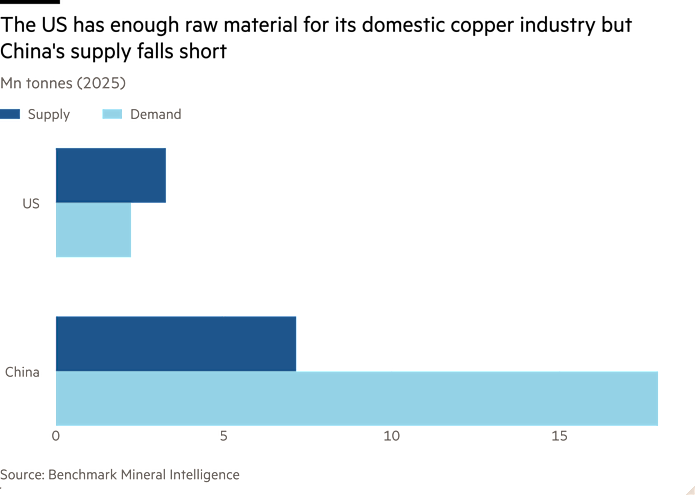

The US has access to more than enough raw copper to meet domestic demand, according to new research on the crucial metal that suggests developing processing capacity is more important than an expansion of stockpiles planned by the Trump administration.

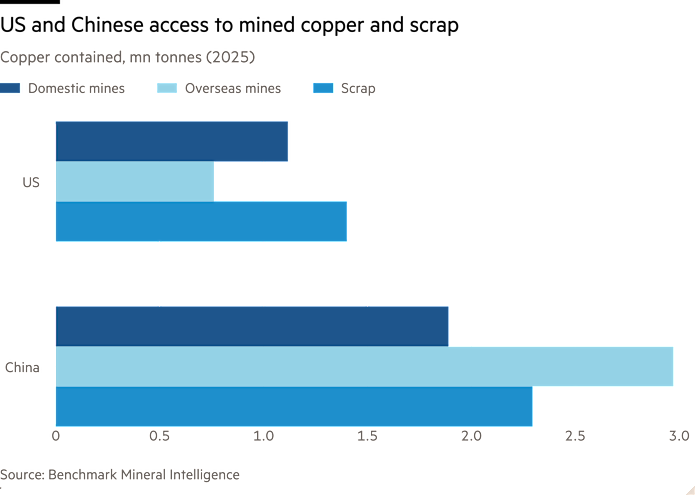

The country can meet 146 per cent of annual demand using raw copper from overseas and domestic mines and from scrap, analysis by Benchmark Mineral Intelligence found. The figure for China — the world’s largest consumer — is 40 per cent.

Copper prices have surged in recent months and the metal, vital for data centres, power grids and electronics, has become a focus for western policymakers eager to secure supplies of critical minerals and reduce reliance on China. The US has launched a $12bn minerals stockpiling effort.

“The US is producing more copper than it uses, and is far more self-reliant than China in terms of raw materials,” said Benchmark analyst Albert Mackenzie. The US problem was “downstream” due to its limited processing capacity to turn raw copper into the copper cathode used by manufacturers.

Meanwhile, “people talk about excellent self-sufficiency from China, but they are [far from] that given how much they need”, he said.

The analysis raises questions about the accelerating US push to secure mines that produce raw materials as a way to sever its reliance on other nations for minerals, and throws a spotlight on the need for processing capacity.

As well as its stockpiling effort, Washington has moved to increase US corporate ownership of mineral assets in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“Stockpiling metal ores doesn’t help if you don’t have midstream processing,” said Stephen Empedocles, chief executive of US lobbying firm Clark Street Associates, which has worked on some recent mining deals. US mining companies were eager to make that point to the Trump administration, and it had gained traction over the past year, he said.

Benchmark’s research looked at the raw material needed by the US and China for the domestic production of semi-finished products like brass, wire and rod, which have uses in sectors such as home appliances and grid infrastructure.

The London benchmark copper price has risen about 40 per cent since October to hit a record high of $14,000 earlier this year, due to supply disruptions and concerns about a looming shortage as demand grows.

The US has a sizeable domestic copper mining industry and produces significant quantities of scrap. But a lack of domestic processing means both are exported in substantial volumes, often to China, to be turned into the copper cathode used in manufacturing. Cathode is also imported into the US for use by semi-finished product manufacturers.

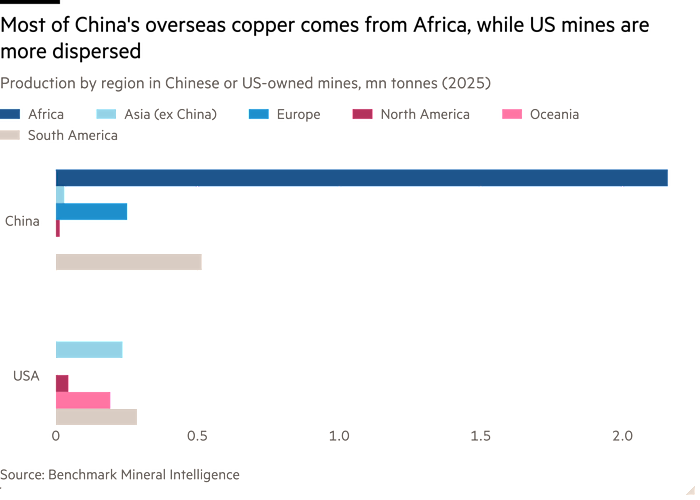

The lack of domestic processing also means that copper from US-owned mines overseas often does not go to the US, whereas much of the material from Chinese-owned assets overseas does go to China. Even excluding US overseas investments, however, the nation should be self-reliant in copper due to its domestic mine and scrap production, Benchmark found.

For the US, “the bottleneck is at the processing stage”, said Mackenzie. If the goal is self-sufficiency, “there’s no point making more raw materials if you’re not going to process them into copper domestically.”

Beijing has spent years developing a huge fleet of smelters domestically, as well as buying and building mines at home and overseas. But China is such a large copper consumer that the material from its domestic and overseas mines combined with scrap is not enough to meet its domestic needs.

China’s build-out of copper smelters, meanwhile, has put the facilities in competition with each other, driving down their profitability. That makes it difficult to justify investments in new smelters in other parts of the world, in the absence of financial support from governments, analysts say.

“There’s overcapacity” in copper smelting, which was putting “pressure” on the facilities, said Iván Arriagada, chief executive of Chilean miner Antofagasta, told the FT.