Ever since Frank Dikötter’s first book, The Discourse of Race in Modern China (1992), this prolific star of China studies has challenged conventional truths and broached taboo subjects. Earlier in his career, he often dealt in sexy topics such as race, sex and drugs — which was why, already in the 1990s, Dikötter’s histories sold like paperback novels.

In the 2000s-2010s, Dikötter widened his reach, becoming perhaps best known for his stark trilogy on Mao Zedong’s years in power: The Tragedy of Liberation (2013), Mao’s Great Famine (2010), and The Cultural Revolution (2016). Mao’s Great Famine won much acclaim but also attracted significant criticism. In that book, Dikötter painstakingly recounted the horrors of the Great Leap Forward in a way that (according to some of his detractors) was overly polemical.

Yet read as a whole, Dikötter’s body of work does read like a grave indictment of the Communist regime, which is one reason why he is not well-liked by the Chinese authorities. Once, while researching in a remote archive in Gansu province (in northwestern China) that Dikötter had also visited, I had to go out of my way to convince the archivists that, no, I had never heard of this dangerous helanren (Dutchman) who had seen and written about the regime’s secrets. Only then was I allowed to see some of the same documents.

If Dikötter has long held a leading position on the Chinese Communist Party’s blacklist, his most recent book will give the authorities no ground to demote him. Red Dawn Over China is a history of the CCP’s rise to power over decades from its obscure origins in the early 1920s to the triumphant end of the Chinese civil war in 1949. To say the least, it was a very bloody affair.

Those who have read Dikötter will immediately recognise his no-nonsense style, which intersperses dry numbers (thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of deaths) and occasional stories that shed light on how some of these people died. In this book he recounts the story of the CCP’s rise as a non-ending series of crimes, some very meticulously described. Numbers . . . numbers . . . someone gets shot. Numbers . . . numbers . . . someone gets buried alive. Numbers . . . numbers . . . someone gets their head smashed by a rock. Numbers . . . numbers . . . someone gets eaten. Voilà, behold the dawn of Communism.

Dikötter’s general argument is, as he puts it, that “Communism was never popular in China.” It was imposed on the Chinese through systemic, unrelenting violence.

But why did Mao and his comrades succeed? Why couldn’t they be stopped in their tracks, rolled back and finally defeated? Dikötter offers a nuanced answer that highlights several important factors.

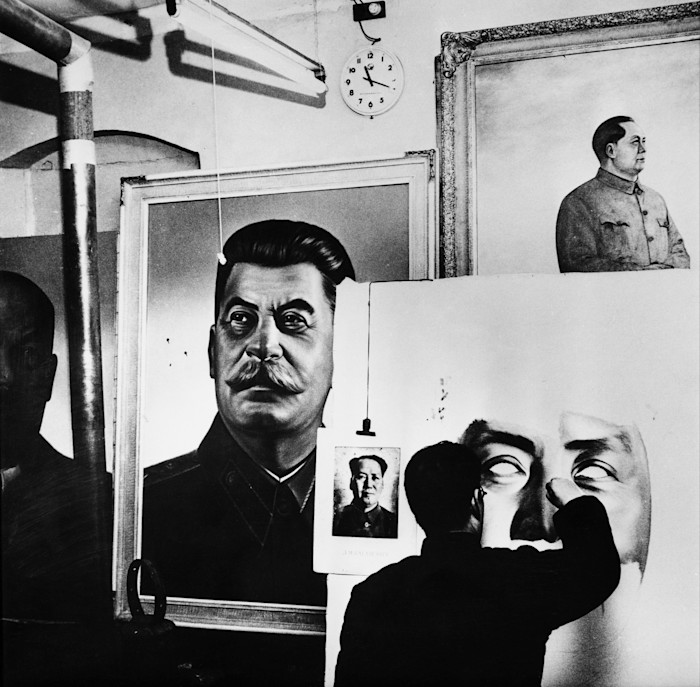

First, the Communists could spin a good story. They were very successful at pulling the wool over the eyes of foreign visitors, such as American journalist Edgar Snow, whose Mao biography Red Star Over China (1937), depicted the Communist leader as a wise poet-philosopher intent on rescuing China from poverty and humiliation.

These foreigners would then advertise the CCP’s benign policies to the wider world, undercutting support for nationalist government leader Chiang Kai-shek, who was at pains to prove that the “Communist bandits” (as he liked to call them) were not at all well-meaning democrats and patriots but ruthless executioners of the Kremlin’s will.

What the foreigners missed out on were the realities of the CCP’s rule: brutal repressions and over-taxation of peasants, opium cultivation and even outright banditry: these kinds of unsavory details were airbrushed out of the official history of the Communists’ march to power.

Second, Dikötter argues, the CCP more often than not enjoyed Joseph Stalin’s support. Moscow had an extensive network of agents in China, who worked diligently towards the overthrow of China’s legitimate government while clandestinely supporting the CCP. Stalin’s role, Dikötter shows, was especially salient in the late 1940s, when Chiang’s forces battled the Communists for the control of Manchuria. He makes it clear that were it not for Stalin’s material help, it is unlikely that the Communists would have won.

Dikötter also blames the US for not helping Chiang. In fact, he shows that the Truman administration, guided by ill-conceived notions about the Communists’ good intentions, actively obstructed his efforts to deal with his foes, with disastrous results.

Third, the country had been devastated by years of war and civil strife. “China came out of the [second world] war with a collapsed economy, tens of millions of displaced people, severe shortages of foodstuffs, its factories and transportation destroyed and entire cities reduced to rubble,” Dikötter writes. Someone had to take responsibility for the chaos — and it wasn’t the Communists. In short, Chiang Kai-shek was unlucky.

Although Dikötter does not give Chiang a complete pass, the old Generalissimo certainly comes out of this book looking relatively good. Yes, he was occasionally brutal, quite possibly corrupt and even potentially an aspiring fascist, but no worse and often much better than the unscrupulous and treacherous Communists.

Dikötter succeeds at bringing these different strands together in a highly readable narrative that challenges the foundational myths of the CCP. There was no heroism, no glory, no grassroots enthusiasm for the Communist cause. Just endless brutality perpetrated by a deeply illegitimate movement that never had much of a purchase among the general populace.

The book is also a valuable reminder that today’s China — the prosperous, technologically advanced superpower — is a country built on a foundation of violence. “Political power,” Mao Zedong argued, “comes out of the barrel of a gun.” A tireless chronicler of the numerous crimes and follies of Chinese Communism, Dikötter once again shows his readers who was pulling the trigger of that gun, and at what cost to the long-suffering Chinese people.

Red Dawn Over China: How Communism Conquered a Quarter of Humanity by Frank Dikötter, Bloomsbury £25/$33, 384 pages

Sergey Radchenko is the author of ‘To Run The World: The Kremlin’s Cold War Bid for Global Power’ (Cambridge)

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X