Myanmar’s military is set to cement its grip on power with what critics are calling a sham election, as the junta looks to gain a veneer of credibility after years of civil war that have ravaged the south-east Asian country.

The military, which came to power in a coup in 2021 after ousting Nobel Peace Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi’s government, is holding a three-phase election that has been widely condemned as being tilted in its favour. The final round of voting is taking place on Sunday.

With Aung San Suu Kyi and other pro-democracy leaders imprisoned, opposition parties dissolved and under what the UN has described as an atmosphere of “fear, violence and mass repression”, the election results are a foregone conclusion — a win by a junta-backed political party.

A nominally civilian government controlled by the military could boost business with China, the junta’s main backer, and some of its neighbours, though analysts warn it would do little to end the fighting or rehabilitate ties with western nations.

Beijing, which urged the military to hold the vote, has been propping up the regime with an eye to bringing stability to its 2,100km-long shared border and creating a more conducive investment environment for its companies, analysts say.

The elections are “part of a wider roadmap for yet another controlled transition, which will bring some semblance of civilian rule that is controlled by the military”, said Morgan Michaels from the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

“But not for the purpose of . . . democratising or supporting human rights, but just because it’s a more sophisticated way to exercise your power and protect your interests, to have some sort of facade,” he said.

China backs the regime because of “the absence of a credible alternative that could step in and keep the country together. There is no other option from China’s perspective”, he said. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The election, which analysts say is a procedural move to abide by the 2008 constitution drafted by the military, will pick officials for Myanmar’s parliament. An electoral college comprised of MPs from the upper and lower houses will then choose the president.

Local media and analysts suggest that General Min Aung Hlaing, already acting president, will take over the presidency. If he does, he will have to give up his military position as per the constitution — but he is likely to pick someone loyal to him to ensure his political security.

The Union Solidarity and Development Party, a political party aligned with the military, leads at the end of the second phase of voting, media in Myanmar has reported, citing a tally from the election commission.

Major political parties have not been allowed to participate. The UN also said many in Myanmar are being coerced into casting votes; the junta said the turnout in the first phase is just 52 per cent. A new “election protection law” is being used by the regime to detain those opposing the election.

“By all measures, this is not a free, fair nor legitimate election. It is a theatrical performance that has exerted enormous pressure on the people of Myanmar to participate in what has been designed to dupe the international community,” Tom Andrews, the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, said this month.

Myanmar last held a general election in 2020, when Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party won a second consecutive landslide victory.

But the military ousted the NLD government just months after the victory and arrested Aung San Suu Kyi, claiming that the election had been rigged and bringing an end to a fragile truce between the two sides.

The coup met widespread resistance in Myanmar, leaving the deeply unpopular military to fight armed ethnic groups and other opposition groups, and a civil disobedience movement. Thousands have been killed in the conflict.

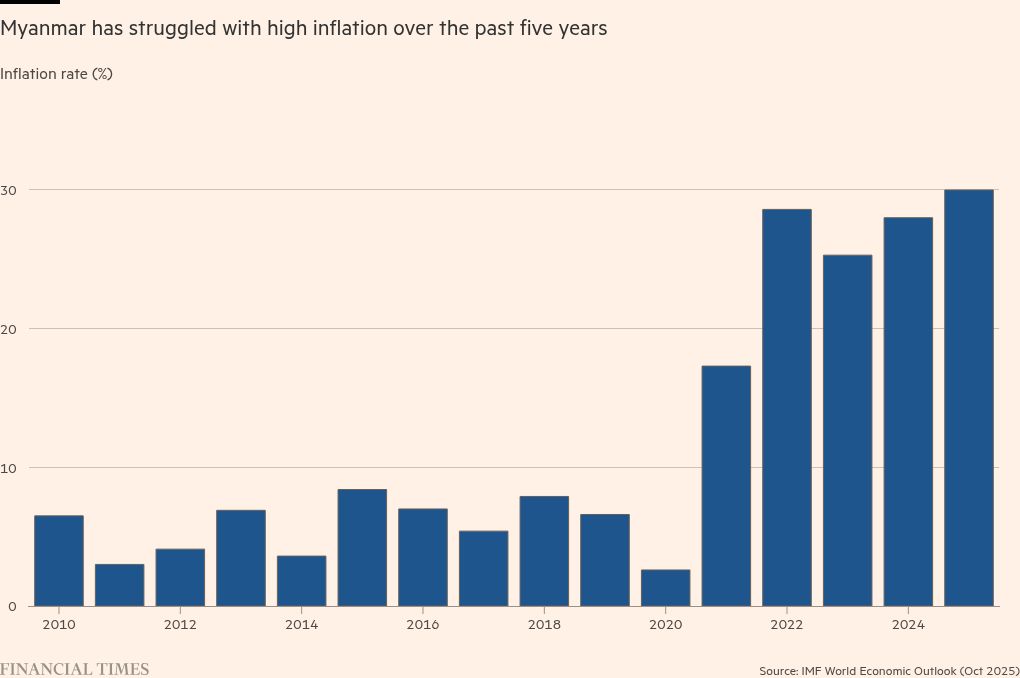

The economy is in shambles, with inflation reaching nearly 30 per cent last year. The coup prompted sanctions from the US, UK and others. Many foreign companies suspended investments or left.

Over the past year, the military has slowly clawed back territory and secured its position — with a helping hand from China, which had initially backed the rebels with arms. “China switching its position has really been quite significant,” said Richard Horsey, a senior adviser on Myanmar at the International Crisis Group.

“China believes that Myanmar will be a mess for a very, very long time to come, and that China can’t do very much to change that reality. But they believe that a nominally civilian government operating under the constitution will be more predictable and definitely preferable to the alternative, which would be a power vacuum,” Horsey said.

China has several Belt and Road infrastructure projects under way in Myanmar, including rail links and a deep-sea port, and many of those are facing disruptions or delays due to the civil war. Beijing’s support for the junta has “left them with enormous leverage in the country”, Horsey said.

While fighting between the regime and opposition forces will continue, analysts say western nations are still unlikely to engage with a new Myanmar government post elections in a meaningful way, but India and other neighbouring countries in south-east Asia could look to forge closer ties.

“I do think that they might have an improvement in their diplomatic situation,” said Horsey.

Post election, the military could do more to persuade some of the rebel groups to negotiate a peace agreement to bring about stability in border areas. Sai Kyi Zin Soe, a Myanmar expert at the University of Sydney, expects “managed instability” where the conflict continues “without any major form of disturbances that could spill over into Asean or the rest of the neighbouring countries”, he said.