At a recent high-level government conference in Beijing, senior officials basked in China’s success the past year in its trade war with Donald Trump, boasting that the country’s system of state-directed planning was superior to unfettered US-style capitalism.

“Our five-year planning system ensures policy consistency and continuity — something western politicians can never achieve given their constant changes of government,” one senior cadre told the gathering of about 200 people in a central Beijing hotel.

For Beijing, the tariff war is the clearest evidence yet that President Xi Jinping’s strategy of investing heavily in high-tech production and industrial self-reliance is paying off, despite persistent deflation at home and growing complaints from abroad about soaring Chinese trade surpluses.

Trump’s attempt to unilaterally impose tariffs on Chinese goods last year ended with him being forced to agree to a one-year trade truce with Xi at a summit in South Korea during October.

The stand-off, during which China threatened to block US access to the rare earth metals vital to many advanced manufacturing processes, demonstrated for the first time Beijing’s ability to stop even Washington from decisively closing its markets against Chinese-made products.

Analysts say it will embolden China to push ahead with its export-led growth model and compete with the US for 21st century technological and economic supremacy. Beijing’s new 15th five-year plan for 2026-2030, due for release in March, envisages China not only dominating legacy industries such as steel making or toy manufacturing but also future technologies, such as robotics and artificial intelligence.

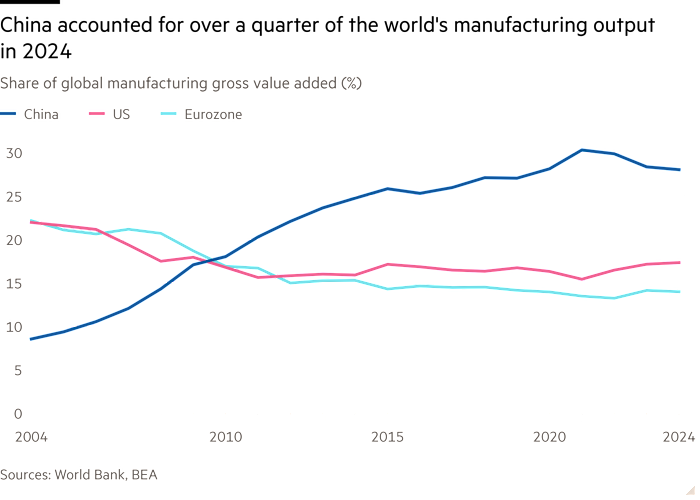

“This is a zero-sum game,” says Joerg Wuttke, a partner at consultancy DGA Group and former European Union Chamber of Commerce in China president. Based on the five-year plan goals, he predicts China could raise its global share of manufacturing from about 30 per cent to 40 per cent.

“They’re telling other countries, don’t mess with us, don’t compete with us, you can’t beat us,” he says.

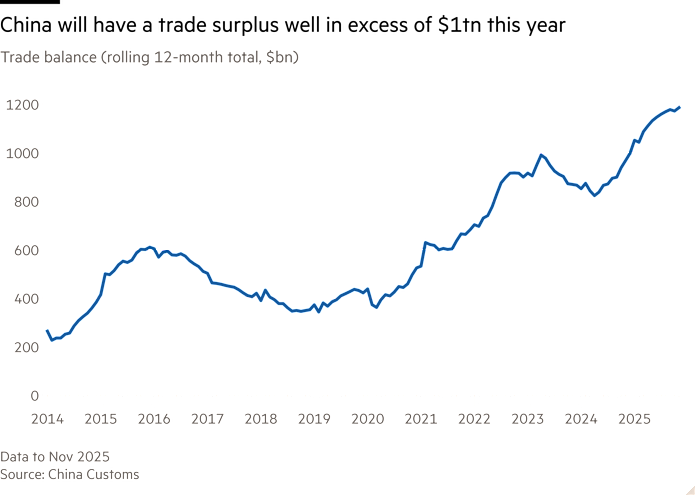

But even as China touts its domination of global manufacturing — trade figures released in December show it is set for its first surplus in goods of more than $1tn in 2025 — vulnerabilities are building in its domestic economy.

A prolonged property market slowdown has undermined local government finances, household sentiment and domestic demand, leading to deflation and falling wages. Policymakers are trying to balance keeping the country’s export machine running while issuing ever more debt to prop up the weakening domestic economy.

“In the past few years, it’s been the property sector dragging down the economy,” says Hui Shan, chief China economist at Goldman Sachs. “At this juncture, I think the economy is now dragging down property.”

The IMF’s managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, said in Beijing in December that China needs “more forceful measures to be implemented with greater urgency”, urging it to fix its “imbalances” in its economy. Such a large country cannot survive on exports alone, she added.

“Boosting consumption would unlock . . . a more durable source of growth.”

At the Communist party’s Central Economic Work Conference in December, the meeting that sets priorities for the following year, Xi and other senior leaders celebrated China’s “significant enhancement of its hard power” over the past five years, according to state media.

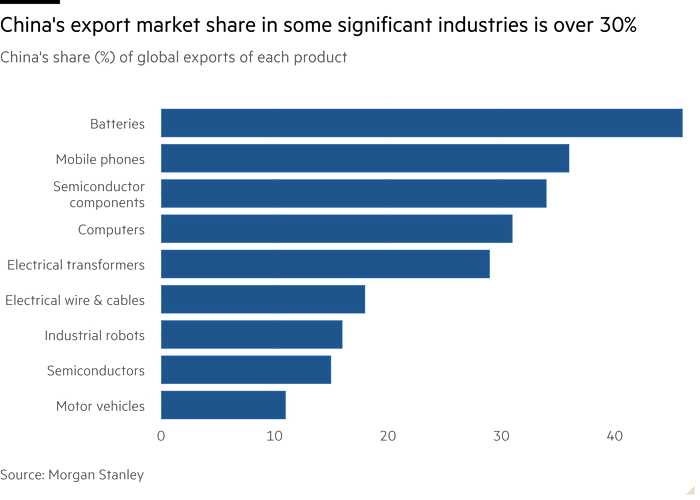

Three years after China’s economy emerged from its strict Covid controls, its global export market share has risen to 15 per cent, up from about 13 per cent in 2017, and is set to rise to 16.5 per cent by 2030, according to a study led by Chetan Ahya, chief Asia economist at Morgan Stanley. China’s share of global manufacturing value added has risen to 28 per cent.

Its trade goods surplus with the US had fallen to $239bn as of September 2025 on a 12-month trailing basis from a peak of $418bn in December 2018, according to US Census Bureau data — though much of the difference is thought to have been products redirected to the US through other countries, such as Vietnam and Mexico.

Ahya attributes part of China’s latest export success to its state-led model, which pushes investment into emerging sectors such as green energy, “even if ahead of [its] time”. China backs its bets with direct state investment in infrastructure and manufacturing, state bank lending, tax incentives and subsidies.

Other economists say the whole society is geared towards production — from the financial and education systems down to rules governing residency that create a huge pool of cheap migrant labour.

China’s strategy is to reduce its own dependence on other countries while increasing their reliance on its supply chains, analysts say. The next five-year plan should call for “substantial improvements in scientific and technological self-reliance”, according to recommendations from the Communist party’s Central Committee.

The aim of the leadership is to build “an economic fortress”, says one government adviser in Beijing, achieving self-reliance in everything from food to tech but keeping trade open for Chinese exports and to absorb foreign technology. It also plans to fortify its export machine by setting up factories in other countries, allowing it to circumvent tariffs and further embedding Chinese companies into global supply chains, and trading in intermediate goods.

“In countries such as Vietnam and across south-east Asia, many primary goods are exported from China as intermediate products, processed locally, and then re-exported under foreign brands — forming a new and increasingly important trade pattern,” said the senior government official at the conference in Beijing.

In the meantime, China would welcome foreign investment into its domestic market, the official said, provided it fostered “advanced manufacturing, modern services, high-tech industries and sectors related to energy conservation and carbon reduction”.

The days of US, European and Japanese manufacturers using China as a cheap assembly line are ending. Many such companies report a growing sense that they are unwelcome in China unless they bring superior or new technology.

A recent report from the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, “Dealing With Supply Chain Dependencies”, stated that “European companies in some strategic sectors are being pushed out, due to regulatory barriers or formidable competition that has benefited from China’s industrial policies.”

During a recent visit to Beijing, one senior European businessman says he was shocked by the reception he received at one of the ministries. Previously welcomed as a valued foreign investor, he said a senior figure at the ministry treated him like a diplomatic adversary and accused Europe of being an unreliable partner.

Others told him the Europeans should stop fixating on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and human rights. “We like Donald Trump,” another official told him. “Why? Because he doesn’t talk about Ukraine and human rights. We can make deals with him.”

Europe is China’s biggest export market after south-east Asia, but Beijing’s success in the trade war with Trump has made it more dismissive of all-comers, the person says.

“China is single-handedly focused on the United States,” the person says. “They think that if they can handle Trump, they can handle Europe easily.” He adds: “The Chinese believe that ‘we can always deal with Europe on our terms. And if it’s not on our terms, we don’t talk to them’.”

Yet for Europe and China’s other large trading partners, the country’s increasing trade imbalances are becoming, in the words of French President Emmanuel Macron, “unbearable”.

In an article in the FT last month, Macron called on China to “address its internal imbalances” or “Europe will have no choice but to adopt more protectionist measures”. Its goods surplus with the EU last year was €305.8bn, compared with €297bn in 2023 and a record €397bn in 2022.

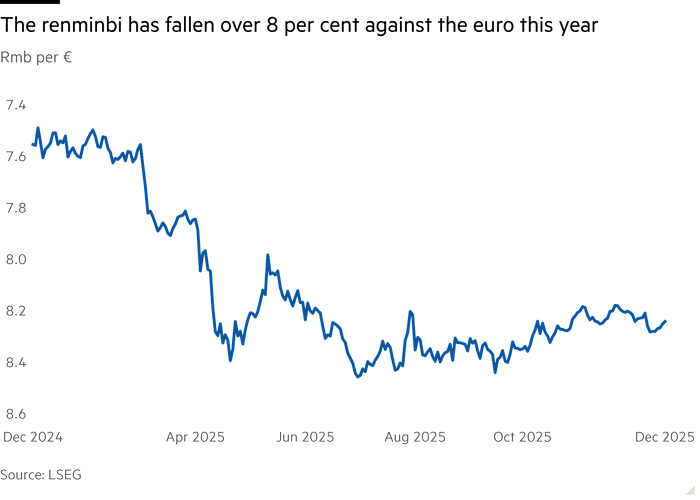

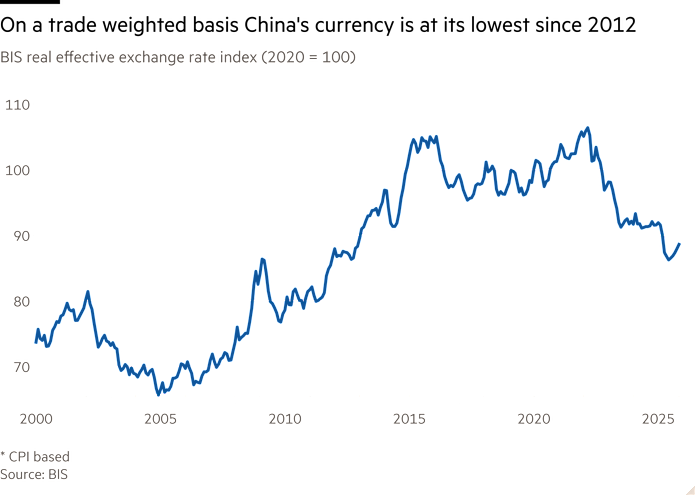

Aside from China’s industrial policies and barriers to entry, a further problem for its trading partners is its currency. The renminbi depreciated by about 8 per cent against the euro during 2025 in nominal terms, and economists estimate that the real effective exchange rate — a weighted average against a broader basket of currencies — has fallen 18 per cent from its peak in March 2022.

This real depreciation is being driven by China’s persistent deflationary pressures. Producer prices have declined every month for more than three years as supply outstrips domestic demand in almost all sectors.

The decline in prices also masks an increase in the volume of China’s exports, which has increased its global market share. “In real terms, the increase in that gap between exports and imports has been larger than in nominal terms,” says Louis Kuijs, chief economist of Asia Pacific at S&P Global Ratings, who estimates that China’s goods export volumes have risen 43 per cent since early 2020 but imports of goods have risen just 15 per cent.

China’s real exchange rate is likely to continue falling over the next two to three years, given Beijing’s limited efforts to combat domestic deflation, according to New York-based Rhodium Group.

“A weak renminbi, persistent deflation and excess capacity in China will . . . steadily erode the bite of conventional trade defence tools,” Rhodium said in a December report on the outlook for the renminbi. “That leaves European policymakers with hard choices: either accept ever-growing exports from China . . . or move towards structural action that restricts trade.”

But for China’s trading partners, using tariffs or other steps to counter its surpluses is bound to meet with stiff resistance — as Trump discovered.

“Other countries will find it increasingly difficult to impose tariffs on China because . . . the supply chain leverage that China has is indeed quite powerful,” says Goldman’s Shan.

China’s control of rare earths — it accounts for 90 per cent of global refining capacity — is mirrored across several other industries, such as batteries for electric vehicles and drones and the refining of the lithium and cobalt that goes into them, says Eddie Fishman, author of Chokepoints.

“We saw earlier this year, even if big US tariffs might be able to inflict pain on China, you can’t do it without causing a recession at home,” Fishman says.

One of China’s most striking supply chain chokeholds from a western perspective, he says, are active pharmaceutical ingredients used to make medicines. In some, he estimates that China has 80 per cent market share.

As China moves up the value chain, dominating the technologies of tomorrow such as electric vehicles, the US and other countries are becoming more vulnerable, he adds.

Even in semiconductors, while the US retains a technological edge, China’s strong position in legacy chips was shown during the recent dispute at Nexperia. When the Dutch government seized temporary control of the Netherlands-based but Chinese-owned company, Beijing responded by blocking Nexperia’s exports.

The US has its own leverage, such as its control of the global financial system through the dollar, but Donald Trump’s threats to the institutional independence of the Federal Reserve and China’s own efforts to internationalise its payments system and diversify its reserves risk eroding that.

“I think if China is allowed to persist with this economic model . . . and the west doesn’t respond with anything besides hoping that market forces sort it out, then yes, China is going to seize more chokepoints over time,” says Fishman.

China’s trading partners among emerging economies are especially vulnerable to this kind of coercion, economists say. Developing countries need Chinese inputs for their own manufacturing sectors, but are at risk of losing their industry because of cheap imports.

“Chinese mercantilism is at least as big a threat, if not much bigger, to the prospects of emerging countries as American tariffs are,” says George Magnus, research associate at Oxford university’s China Centre and former chief economist of UBS.

A thousand kilometres from Beijing, in China’s ancient capital Xi’an, Chen does not share the confidence of the party’s economic cadres.

“It was better in previous years,” says the food stall owner, who declined to give his full name, as he looks out at the throngs of tourists passing through the vast Grand Tang Dynasty Everbright City shopping district. “Sales began to decline [in 2024] and have not been good [in 2025].”

The buildings here are modelled on those of the dynasty that ruled China from the 7th to the 10th century, and many tourists rent period costumes to pose for photos. But there are few other signs they are spending money.

Since last year, President Xi has increasingly emphasised the importance of domestic demand for the economy, with the party’s magazine Qiushi releasing a collection of his past speeches on the subject in December.

The party has announced birth subsidies, lifted restrictions on real estate prices and, in a bid to tackle deflation, launched a campaign against “involution”, seeking to stop companies engaging in destructive price competition.

But the party’s piecemeal moves have failed to decisively lift sentiment or reflate the economy. Retail sales expanded 1.3 per cent in November against a year earlier, the slowest pace of growth since December 2022, when China lifted its Covid restrictions. Property prices and investment have plunged. While a large part of the investment fall could be due to statistical issues, analysts believe at least some of it is real.

The faltering domestic economy, weakened by a property slump that started in 2021 when Beijing sought to deleverage the sector, is the alter ego of China’s export boom. Deflation makes China’s goods more competitive on international markets, but at home it erodes corporate profitability and increases debt relative to profit or revenues. Private sector economists have warned for years about the limits of China’s export and investment-led growth model, but now even some government advisers are chiming in.

At the conference in Beijing, a government adviser from a prominent state think-tank pointed out that China’s GDP deflator, the widest measure of prices in the economy, had been negative for a record 10 consecutive quarters, surpassing the seven-quarter record set during the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s.

“Persistent price declines create a disconnect between the data and how the economy feels, since they affect both household incomes and corporate profits,” the adviser said. “Falling prices not only distort perceptions but also dampen expectations, making it harder to boost consumption or drive investment.”

To boost domestic demand, the adviser argued, China should increase the share of fiscal spending devoted to public services such as education, childcare, healthcare and social security — measures that would indirectly lift household purchasing power. The greater potential, he added, lies in services rather than goods.

Goldman’s Shan says tackling the root macroeconomic causes of the domestic slowdown, such as the property slump, would be the best way of reflating the economy.

For now, however, there is no end in sight for Xi’s supply-side driven economic path. A large-scale domestic stimulus targeting household incomes would mean directing funds away from the investment and high-tech manufacturing-led model, which was still favoured by policymakers.

“Policymakers think of it [the supply-driven model] as a success, not a failure,” says Shan. “And with the rare earth leverage helping China to manage trade tensions, it’s going to extend the runway for China’s exports too.”

With additional contributions from Cheng Leng and Wenjie Ding in Beijing