Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Mining myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

For years, the only buyers for the antimony Jabbar Khan sourced from wildcat traders in Afghanistan were secretive Chinese intermediaries, who bargained hard over the price.

Now, Khan, chief operating officer at Himalayan Earth Exploration company, is fielding calls from US buyers interested in stockpiling the silvery-white rock vital to the production of missiles, batteries and flame retardants from Pakistan and central Asia.

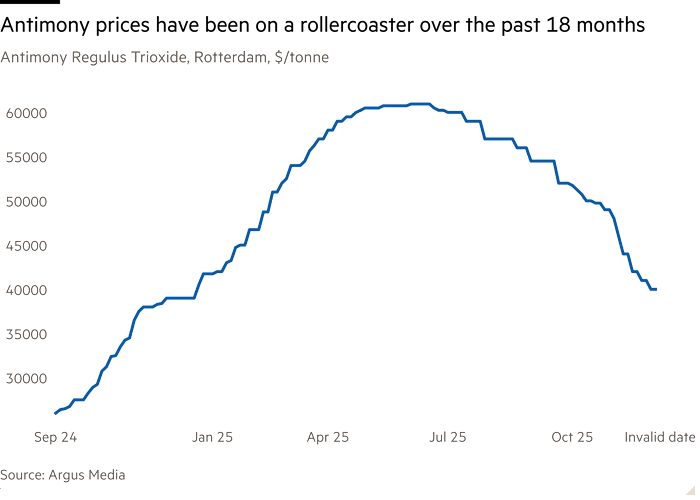

The price of antimony trioxide has shot up to around $40,000 per tonne — off its peak of more than $60,000 as some users seek alternatives but still substantially higher than $26,000 in September 2024 — as fears about China’s control of the supply chains for metals including antimony have sparked a global race to secure supplies.

Thanks to US President Donald Trump’s desire to secure critical minerals, “the conversations we had been pushing for seven years, especially around antimony, finally started gaining traction both in Pakistan and the United States”, said Liaqat Ali Sultan, the chief executive of Himalayan.

Pakistan at present produces a small amount of mined antimony — much of it on the mountainous border with Afghanistan where militants this year have killed more than 1,700 people — and holds just one per cent of the world’s reserves, according to the US Geological Survey. China has around a third of global reserves while Russia has almost a fifth.

But so eager is Pakistan to reap the rewards of the global race for critical minerals that advisers to Field Marshal Asim Munir, the country’s army chief and its de facto most powerful official, have suggested building a bespoke terminal to ferry antimony to the US.

Last month, Pakistan-based Himalayan signed a “strategic partnership” with Nova Minerals, a company dual listed in Australia and the US, to “strengthen US-Pakistan economic ties” through exploring for antimony.

Nova, which received a $43mn grant from the US defence department this year to explore for gold and antimony in Alaska, does not at present produce any antimony but said in September that it aimed to produce “military-grade antimony by 2026/27”.

Christopher Gerteisen, Nova’s chief executive, said his company will buy “over 100 tonnes” of Pakistani antimony concentrate for about $2mn early next year for testing and processing in Alaska. It may eventually set up “downstream processing” of the ore in Pakistan, he said. “The Department of War encouraged us to go out in the world and find whatever we can,” he added, using the Trump administration’s preferred name for the defence department.

Missouri-based US Strategic Metals in September agreed with Pakistan’s military and political leaders to collaborate on “critical minerals essential for the defence, aerospace and technology industries”. The company’s planned US processing plant and mine are not yet operational. It received a small sample of Pakistani antimony in October for quality testing.

Tajikistan, the second-largest antimony producer and a neighbour of Pakistan’s, is also benefiting from US attention. In a White House meeting with Trump last month, Tajik president Emomali Rahmon praised the ex-Soviet nation’s “brilliant co-operation” with the US on exporting the mineral.

Even if antimony can be mined, processing expertise remains concentrated in China. “The recent global price surge was driven not by a shortage of ore, but by limited processing capacity outside China,” said Cristina Belda, an analyst from Argus Media. The number of smelters capable of processing antimony outside China “remains limited”.

Many miners complain that Pakistan remains at the lower end of the value chain, with little processing or refining capability. “Almost all of our raw antimony comes out of artisanal mines from north-west mountain regions and disappear into the hands of Chinese buyers at Karachi’s port, usually far below market rates,” said one veteran of Pakistan’s mining sector.

Another observer said there were concerns about antimony sourced in Pakistan having been mined in Afghanistan and “walked over the border”. The market for antimony was the “wild west”, said one expert.

The US government agreed this year to buy antimony from Texas-based US Antimony Corp. The processing company has added around $6mn worth of antimony to its inventory this year, a combination of metal and mined material sourced from third parties. USAC said it had not bought from China.

Antimony prices have fallen from their peak this year as new supply has come out of south-east Asia and buyers seek substitutes such as zinc borate and stannate. “The reality” was that buying was “soft right now and people are threatening substitution,” said one trader.

Still, Nova’s Gerteisen says that he and other US buyers are willing to offer prices well above those of Chinese competitors in a region that Beijing considers its backyard for the metal. “Pakistan is virgin country for mineral exploration.”