At an industrial park in Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, a billionaire is embarking on the next phase of China’s green revolution.

Zhang Lei built Envision into one of the largest wind turbine manufacturers in the world. Now the entrepreneur is using wind energy to produce so-called green ammonia, selling it for use in fertilisers and chemicals and as a fuel for shipping.

“This is more than a technological milestone,” said Zhang earlier this year. “Scalable, green alternatives are now real and operational.”

While clean fuel technologies are still evolving, experts say companies such as Envision show how China is using its abundant and low-cost renewable energy and biofuels to help decarbonise more of its vast industrial sector.

Though the clean fuels are significantly more expensive than fossil fuel alternatives, the Chinese companies are laying the groundwork to dominate global clean-technology supply chains.

“There is this expectation the scale will allow it to get cheaper — just as solar panels did from 2010 to now,” said David Fishman, a Shanghai-based energy analyst at The Lantau Group, a consultancy.

Ammonia is one of world’s largest industrially produced chemicals with the bulk of production being used as fertiliser and the rest as feedstock for plastics, textiles and cleaning products and in explosives for mining.

Green ammonia, which is made with renewable energy instead of natural gas or coal, is an energy-dense liquid that can be stored and transported easily.

Global demand for the chemical, currently about 185mn tonnes, could grow if it is used as clean fuel for shipping and power generation, though significant hurdles remain before mass adoption.

Shanghai-based Envision has ploughed about Rmb8bn ($1.1bn) into the Chifeng plant. It has an initial annual capacity of 320,000 tonnes and has signed up customers in Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Europe, according to the company. It plans to boost production to 5mn tonnes over the next decade.

Despite the low cost of solar and wind energy in China, the high cost of electrolysers, as well as the lack of storage and distribution networks, has slowed mass commercialisation hopes.

There are still challenges from using unreliable renewable power sources at a large scale, said Frank Yu, who leads Envision’s zero carbon gas and hydrogen energy efforts.

“The process is still evolving,” Yu told the Financial Times. “I believe that from now until 2035 there will still be a lot of improvement on the technology side.”

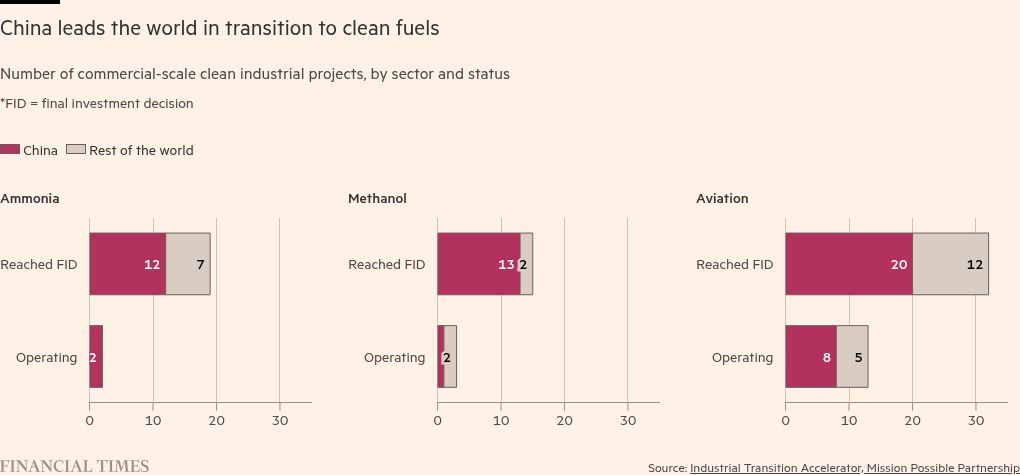

The Chifeng plant is one of 54 commercial-scale clean industrial projects either in operation or financed in China — three times as many as in the US, according to data from Mission Possible Partnership, an international non-profit focused on carbon-intensive sectors.

Many of China’s biggest renewable energy manufacturers, including solar group Longi and wind turbine makers Goldwind and Mingyang, are in the early stages of developing clean fuel and chemical operations. These projects mostly span ammonia, methanol and aviation fuels.

Another example of China’s progress can be seen in the overhaul of a methanol plant in inner Mongolia near Jungar Banner.

The 500,000 square-metre site is operated by Towngas, a Hong Kong-listed utility which delivers gas to more than 300 Chinese cities. Its biggest shareholder is the late tycoon Lee Shau-kee’s Henderson Land Development.

When it started operations in 2011, the project relied on cheap, locally mined coal to produce methanol but since 2021 Towngas started to use scrap tyres as a feedstock.

In an interview at the plant, Towngas green fuels and chemicals executive Tony Lin said that by 2026, half the site’s 300,000 tonnes of annual output will be produced using small pellets made of desert willow.

The remaining 150,000 tonnes will be converted to use the biofuel feedstock by 2028. The desert willow will be harvested from the region’s Kubuqi and Ulan Buh deserts, where it has been planted to slow desertification but needs to be cut back to control excessive drawdown on groundwater.

Methanol is a building block chemical for scores of products, including plastics, synthetic fabrics and fibres, pharmaceuticals and agrichemicals. The fuel is viewed as one way shipping companies can lesson their dependence on heavy fuel oil and marine diesel.

However, the short-term outlook for methanol’s use in international shipping is uncertain. In October, the US and Saudi Arabia derailed the adoption of the International Maritime Organization’s “net zero framework”, which would have set emissions reductions targets and imposed penalties.

Despite the IMO delay, Lin said transitioning methanol production from “grey” to “green” fuels over the coming years was the only option to ensure long-term financial sustainability, as Beijing works to be carbon neutral by 2060.

“We need to turn it green otherwise we won’t survive,” he said.

This year, 12 of the 19 global clean industrial projects that have reached final investment decisions, the last stage to determine whether or not the project will go ahead, are in China.

Faustine Delasalle, executive director of Industrial Transition Accelerator, a non-profit co-funded by the United Arab Emirates government and Bloomberg Philanthropies, said that Chinese developers have a bold vision for the future based on the conviction that green molecules and fuels are the “new oil”.

Delasalle said: “China is definitely leading on the commercialisation, at scale, of the next wave of clean technologies with a big share of the pipeline of projects but most importantly a growing share of a number of projects that have reached final investment decisions.”

The Lantau Group’s Fishman said clean industry projects in China also typically benefit from a “suite” of state policy support, including low interest loans, cheap land and research and development subsidies.

The Chinese Communist party has listed hydrogen among the “emerging and future industries” it wants to accelerate in its next five-year plan. But it has so far stopped short of deeper, nationwide subsidies previously rolled out for other technologies such as electric vehicles and batteries.

Alongside an investment to make machinery used for green hydrogen production in Spain, Envision’s Yu said the company is also exploring green ammonia production in Latin America, Africa and the Middle East.

The biggest headwind for the business, Yu said, stems from uncertainty over decarbonisation policies in many western countries. “Without strong policy for CO₂ emission reduction, how can green fuel compete with fossil fuels?”