No place reinvents itself like Hong Kong, the dynamic city on the harbour. You quickly get used to contrasts – traditional bamboo scaffolding and gleaming buildings, the modern skyline and historic boats. We return for the romantic classics, beloved bars and stately hotels, as well as the exhilarating pleasure of catching up with what’s new. It’s a city that asks you to quicken your pace to keep up with what’s always evolving.

Everything comes together in Hong Kong – boats, humidity, alleys, capital. The harbour at the foot of the steep green hills is so dramatic, it makes the city feel like a theatre: intimate, intense, a thrilling balancing act. The first time I came here, more than 25 years ago, I dutifully visited tailors who made shirts in a couple of days and good suits in a week or two that, alas, no longer fit. These days the arcades have fewer old‑line tailors and more (far more) luxury brands, but that’s the way the world goes.

James Harvey-Kelly – who took the photographs for this story – spent many years of his childhood in Hong Kong. As we explored the city together, he noted the changes. He pointed to a building we could barely make out behind numerous newer skyscrapers. “That building was the tallest in the city when I lived here,” he said, somewhat wistfully. “It was a big deal when it opened.” Now it looked almost quaint.

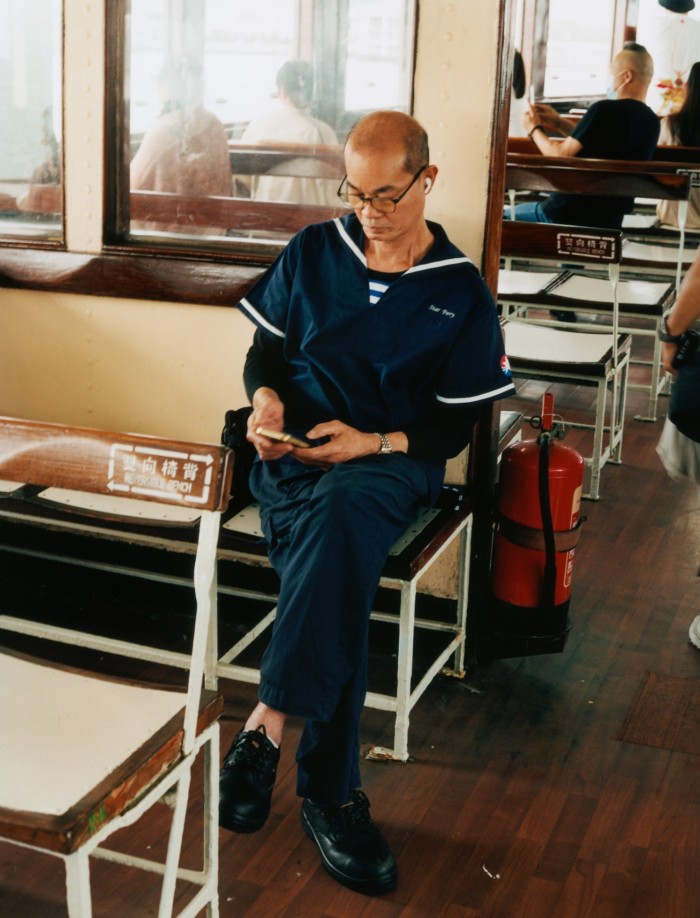

But we didn’t have time to get too sentimental, with our itinerary: dim sum, bars, antique shopping, street life, new architecture, old temples, great hotels and some horseracing. I don’t feel like I’m truly in Hong Kong until I’ve been on the junk, the improbable and convivial boat that crosses the harbour just as it did back in the 1800s. (You can skip the line and enter by tapping the useful Octopus card, which works on most public transport.)

In Man Mo Temple, which dates to 1847, we walked below spirals of incense hanging from the ceiling. The temple brings good luck and was popular, apparently, with scholars who wanted to pass their exams. It wasn’t clear if it would bring us gambling luck at the races. Nearby, along bustling Hollywood Road, are good coffee shops; you’re always happy to head inside for a little air-conditioning. “Humidity is part of life in Hong Kong,” says James. “Everybody’s hot. It’s the great equaliser.” There are also vintage shops and antique stores of every variety; I’m always looking for one that’s full, friendly and fairly priced. We did well at Eastern Dreams, which had a nice selection of lacquer boxes, teak cabinets, porcelain bowls and plenty of other things sadly too large to transport.

A more modern setting is Tai Kwun. Located in a former police station, it includes a heritage and arts centre designed by Herzog and de Meuron, with well-programmed temporary exhibitions, a smart bookstore and café. It is part of a larger cultural momentum. “The art scene has come a long way, with a very dynamic gallery scene and institutions such as M+ and Tai Kwun,” says Alan Lo, a Hong Kong-born and raised collector. “The major auction houses have also invested heavily in new headquarters, which shows a serious commitment to Hong Kong as the hub for the Asian art market.”

Bryceland’s, an outpost of the excellent Tokyo label that specialises in well-made military chinos and Oxford shirts, is in a handsome space in the same building as popular Luk Yu Tea House. Hong Kong tailoring is not about affordable knockoffs. “The culture of the city was always to dress up, and that remains the norm,” says Mark Cho, co-founder of The Armoury. One reason for that? People still go to an office. “Work from home is virtually non-existent,” he adds, but notes that that’s what gives the city its unique energy: “People work and play in public.”

The Armoury, with its celebrated label and elegant Italian suits for big spenders, now shares a floor in the Pedder Building with the handsome Lok Man Rare Books, in the event you’ve got enough room in your bag for an old first-edition. The polar opposite of any international luxury conglomerate is the highly personal design and home goods store Hak Dei, in an unpretentious space in Kowloon. You can find a well-chosen selection of tea cups, bamboo trays, ashtrays and kettles. Owner Chau Chi Pang is usually working behind the counter, and he clearly has a nostalgic appreciation of a better way of doing things. It’s the kind of place where they wrap things in brown paper.

Shopping in Hong Kong can be diverting, but meals are serious. And our dining agenda was suitably rigorous. I could eat dim sum for any meal, and in between meals if given the chance. (When I was cloistered at a fasting clinic in Spain I spent my days staring at photographs of dumplings.) Dim sum always feels joyful to me, large tables of families enjoying long meals as empty bamboo baskets stack up in front of them. We didn’t mess around; the first stop was Man Wah, at the top of the Mandarin Oriental hotel, where we ordered comprehensively: a shrimp har gau with wild mushrooms was so good we had another. Yes, you can have tea with dim sum and probably should, but a good glass of white wine did the trick for me.

For something more avant-garde, there is Roganic, an outpost of the minor empire overseen by British chef and farm-to-table pioneer Simon Rogan. You enter a shopping mall – never very appetising, but very Asian – where behind a modest door is an expansive space with recycled marble floors and reclaimed wooden pillars theatrically twisting towards the ceiling. This is the backdrop for inventive, highly composed dishes prepared in an immense open kitchen and finished at the table. If you like ambitious cooking and natural wine then this is a lovely place for lunch as sunshine fills the room.

Lindsay Jang, an owner of Hong Kong stalwart yakitori joint Yardbird (and also of the new, highly anticipated Always Joy), says: “A lot of legacy businesses are downsizing or closing, but Hong Kong has always had so much international influence that the sheer action of change, demolition and rebuilding is a core characteristic of it.” Always Joy is a long, dimly lit room in the space that previously housed Ronin, Jang and partners’ combination omakase-whisky and seafood bar; it has counter seats overlooking a kitchen where young chefs are hard at work. The Japanese bar food, from sashimi to tempura to dishes prepared over an open fire, is inviting and easy-going.

For a change of pace – lively, bright and a downright good time – we went to the horse races at the Happy Valley Racecourse near Causeway Bay. This is not some pastoral setting in a park; it’s right in the city. In another typically Hong Kong contrast, the stadium is surrounded by apartments that tower over the green grass of the turf track. (For more prestigious races you can head further out to Sha Tin, which usually takes place on weekends and is more of an undertaking.)

At the races, you’ll cross paths with the city’s residents who are committed to the action and handicapping their favourites. There are restaurants and clubs you can pay to get into if you want to be above the fray; I prefer to circulate closer to the track, where you can stroll around with a beer and watch the horses come into the paddock. While waiting for each race to begin you can enjoy (or avoid) live music performed on small stages. The whole production is so festive that you don’t mind not choosing a winner, and we certainly didn’t end up in the money.

Back in town, start your evening on the right foot with a cocktail at the excellent The Chinnery in the Mandarin Oriental Hotel. There are wood-panelled walls, discreet booths and paintings of old Englishmen, if you like that sort of thing. A more airy option is the outdoor terrace at Duddell’s, which also has a well-loved dining room and upstairs café. This is a good place for an easy-going drink, popular with art-world denizens from nearby galleries.

The dining scene in Hong Kong does not stay still. Geoffrey Wu, a dining consultant, says “Hong Kong is always very international”, but that restaurants are evolving to meet modern tastes. “More bars are introducing zero ABV drinks as younger generations are drinking less,” he says. These bars are ambitious and becoming dining destinations themselves. “Bars are serving food in ways the classic places did not.” That was our experience at The Diplomat, a venue buzzing with young people who have more energy than I do. But they politely brought us their burger (small and justifiably famous), which James rated highly (I concurred).

We had a clear idea about our last dinner. No experimentation, no small plates, no tweezers: we wanted Peking duck in a traditional setting. “It’s my death row meal,” James declared. I wouldn’t argue. At Spring Moon, the Michelin-starred restaurant in the Peninsula, we had a supreme bird, gorgeously crisp skin, expertly carved by our table. You know the rest: wrapped in a warmed pancake, served with hoisin sauce and cucumbers, a perfect equation. The room is stately and handsome, with tables far apart. We ate in silence for a moment, then James spoke for us both: “Damn, that’s good.” A reminder that you don’t need to chase novelty when you’ve found the perfect recipe.

David Coggins was a guest of the Peninsula Hong Kong; deluxe rooms from HK$4,600 (about £477)