Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

The writer is a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy and the author of ‘Chokepoints’

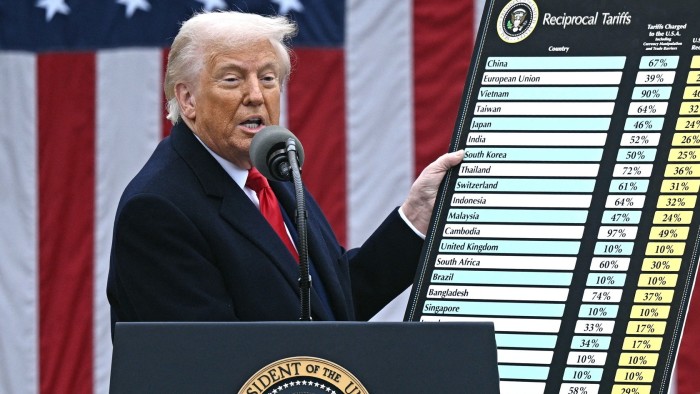

This past summer, Donald Trump’s faith in tariffs appeared vindicated. He sealed lopsided trade deals with the EU, Japan and South Korea, while imposing most of his promised “liberation day” levies without provoking a market meltdown. His trade representative, Jamieson Greer, declared “a new global trading order” in which America uses tariffs to bend the rest of the world to its will.

Trump’s confidence rests on a simple conviction: access to the US market is so vital that other countries will do anything to preserve it. As his press secretary summarised: “Every country wants what we have: the American consumer.” But that confidence is misplaced. Tariffs are a far weaker weapon than the president believes. They are a poor substitute for the modern economic pressure tactics that the US pioneered and China increasingly embraces.

Those “wins” with Europe, Japan and South Korea also tell a misleading story. These are close security allies that depend on Washington’s protection. Their concessions reflected strategic dependence, not economic capitulation. Brussels swallowed an unequal pact to preserve American backing for Ukraine, not because tariffs had forced its hand.

Countries outside the US security umbrella have proved far less pliant. Take India, which has been subject to a 50 per cent duty since August. The Trump administration insists these “secondary tariffs” are intended to compel India to stop buying Russian oil. But the policy is backfiring. Indian refiners are importing more Russian crude, openly defying Washington.

Why? For a start, the tariffs miss the actual decision makers. Indian refiners buy Russian oil because it’s cheap. But Trump’s duties don’t touch them. Instead, they punish unrelated exporters — from garment factories to shrimp farmers — who have nothing to do with Russian oil.

To make matters worse, tariffs turn what should be a business calculation into a political one. Had Trump threatened secondary sanctions, rather than tariffs, on buyers of Russian oil, Indian refineries would face a clear business choice: keep importing Russian crude or retain access to the US financial system. Tariffs, by contrast, demand capitulation from Prime Minister Narendra Modi directly — and no Indian leader can be seen bowing publicly to Washington. Small wonder the tariffs have fuelled resentment across India, while Modi made his first trip to China in seven years to meet with Xi Jinping.

But the biggest problem with tariffs is a basic fact: access to the US market isn’t as vital as Trump imagines. Real geoeconomic leverage comes from chokepoints — parts of the global economy where one country holds a dominant position and there are few, if any, substitutes.

China’s weaponisation of rare earths is a case in point. Chinese companies control 90 per cent of refining capacity. When Beijing blocked exports of seven rare-earth elements to the US in April, it quickly upended supply chains and forced Trump to seek a truce. Earlier this month, Beijing went further, asserting sweeping control over all products containing Chinese rare earths — including semiconductors made in Taiwan and Arizona. It can take such dramatic action for a simple reason: if you can’t buy rare earths from China, you have no alternatives.

Tariffs are a tax on imports. When used as an economic weapon, they exploit America’s role as the world’s largest importer. Yet despite that distinction, the US accounts for just 13 per cent of global imports, well below its 25 per cent share of global GDP. Tariffs deprive foreign exporters of sales but also raise prices and disrupt supply chains at home. Often they hurt American companies and consumers more than their targets, who can redirect trade elsewhere. Tariffs do not exploit a chokepoint, making them a poor source of leverage.

Contrast this with US financial sanctions, which rest on a genuine chokepoint: the dollar. When Washington cuts access to the greenback — which is involved in 90 per cent of foreign exchange transactions — it can devastate a target without causing significant harm at home.

Past presidents understood this. That’s why they reached for sanctions, and not tariffs, when they wanted to apply serious economic pressure. It also explains why Trump’s repeated threats of “secondary tariffs” on buyers of Iranian, Venezuelan and Russian oil have done nothing to curb those countries’ petroleum exports, whereas secondary sanctions have been much more effective in the past.

Now, as China tightens export controls on rare earths, Trump is again threatening to retaliate with a “massive increase” in tariffs. But he is betting everything on the weakest weapon in America’s economic arsenal.