Hello and welcome to Energy Source, coming to you today from London.

Energy costs are high on the agenda in Britain as winter draws in and households start putting the heating on.

Ed Miliband, the energy secretary, on Sunday repeated his party’s election manifesto pledge to bring energy bills down by up to £300 by 2030.

That is despite widespread doubts in the energy industry about whether the pledge is achievable.

The government wants to decarbonise Britain’s electricity system by 2030, which will require massive investment in new wind and solar farms and electricity cables.

Last week, some of the UK’s leading household energy suppliers warned that the costs of investment and other government policies were likely to outweigh any decrease in wholesale prices over the next few years.

What happens in Britain is likely to be watched around the world, given it is trying to move towards renewables faster than many other countries.

For today’s newsletter, my colleague Ryohtaroh Satoh delves into a crucial part of that overhaul — energy storage.

Enjoy reading — Rachel Millard

Global energy storage is starting to grow

The need for electricity storage is becoming more acute as countries roll out more wind and solar power. Electricity prices in Spain are regularly turning negative around midday. Wind farms are having to switch off in markets ranging from Britain to China to avoid swamping the system with too much electricity.

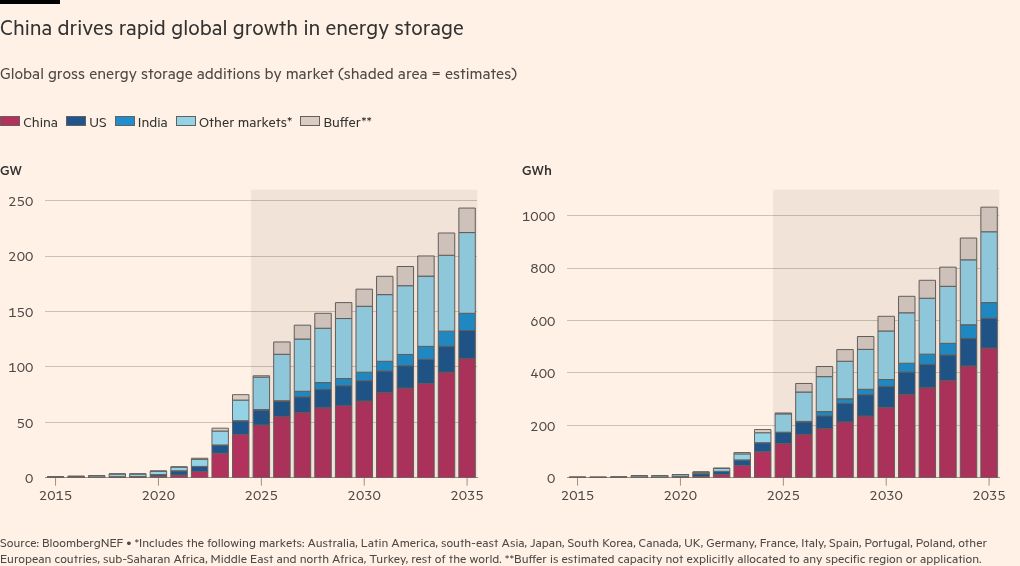

A report out this week from BloombergNEF looks at the extent to which technologies to store electricity are catching up — and China’s huge role. Overall, the picture is strong: BNEF has revised up its forecast for storage capacity in 2035 by 12 per cent.

It now expects the world to have two terawatts of installed capacity, or 7.3 terawatt hours of storage capacity, by 2035. This is roughly 12 times greater than the cumulative capacity in 2024. (To put that figure in context, the UK consumes about 320TWh of electricity a year).

As with renewables, China is leading the way: The country’s installed capacity will account for about 43 per cent of total global capacity, BNEF data shows, boosted by falling costs, political support for the technology and electricity market reforms.

This year alone, it is set to add a record 47.6 gigawatts, or 130.4 gigawatt hours, according to BNEF, 22 per cent more than it added in 2024.

“Higher expectations reflect increased confidence in robust growth across China and the US, despite recent policy shifts, as well as in emerging markets such as Australia, south-east Asia, Saudi Arabia and Africa,” the report said.

While falling costs are a significant driver of the trend, governments in India, Europe and elsewhere have also been pushing the technology forward by running auctions which support projects combining both renewable power and storage capacity, to try and develop stable electricity supplies.

The International Energy Agency says that in 2024, governments commissioned or supported 45GW of renewables through these so-called firm-capacity auctions accounting for more than 25 per cent of the total renewable power awarded globally that year.

This was a significant increase compared with the period from 2021 to 2023, in which the same type of auctions comprised only 5 to 8 per cent, according to the Paris-based intergovernmental energy advisory body.

Firm-capacity auctions have become “a key policy framework enabling developers to provide flexibility”, the IEA said in a report published this month.

Until at least 2028, BNEF expects the vast majority — 80 per cent — of electricity storage to come from batteries able to discharge at maximum output for less than six hours. Longer duration technologies should take greater market share towards the end of the decade.

But a large portion of the popular and cheap lithium iron phosphate batteries are made by Chinese companies such as CATL and BYD, raising questions for the US, which is in the midst of a trade war with the world’s second-largest economy.

President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act will require energy storage projects starting construction in 2026 and onwards to get at least 55 per cent of their components from either US suppliers or non-prohibited foreign entities — in effect preventing projects from relying on Chinese technology — while Washington has also increased tariffs on Chinese goods.

BNEF forecasts that the US will still reach 235GW, or 948GWh in 2035, seven times the cumulative installations in 2024 and making it the second-largest market for storage.

But having to source the majority of their equipment from outside China will push up costs and damage the economics of some US projects. There was “definitely” a lost potential from the trade war, said Isshu Kikuma of BNEF. It will “slow down some of the growth that we could have seen”, he added. (Ryohtaroh Satoh)

Chart by Janina Conboye

Power Points

Rare earths shares have soared as Donald Trump’s attempt to break China’s stranglehold on the supply of critical minerals electrifies the once sleepy sector.

An FT Big Read looks at the costs of Trump’s campaign to censor climate science.

Enthusiasm in the offshore wind industry has collapsed amid economic and political storms.

Energy Source is written and edited by Jamie Smyth, Martha Muir, Alexandra White, Kristina Shevory, Tom Wilson, Rachel Millard and Malcolm Moore, with support from the FT’s global team of reporters. Reach us at energy.source@ft.com and follow us on X at @FTEnergy. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Moral Money — Our unmissable newsletter on socially responsible business, sustainable finance and more. Sign up here

The Climate Graphic: Explained — Understanding the most important climate data of the week. Sign up here