In Hungary’s second-largest city Debrecen, workers are putting the finishing touches to a vast battery factory built by China’s CATL to supply BMW, Mercedes and other European car brands.

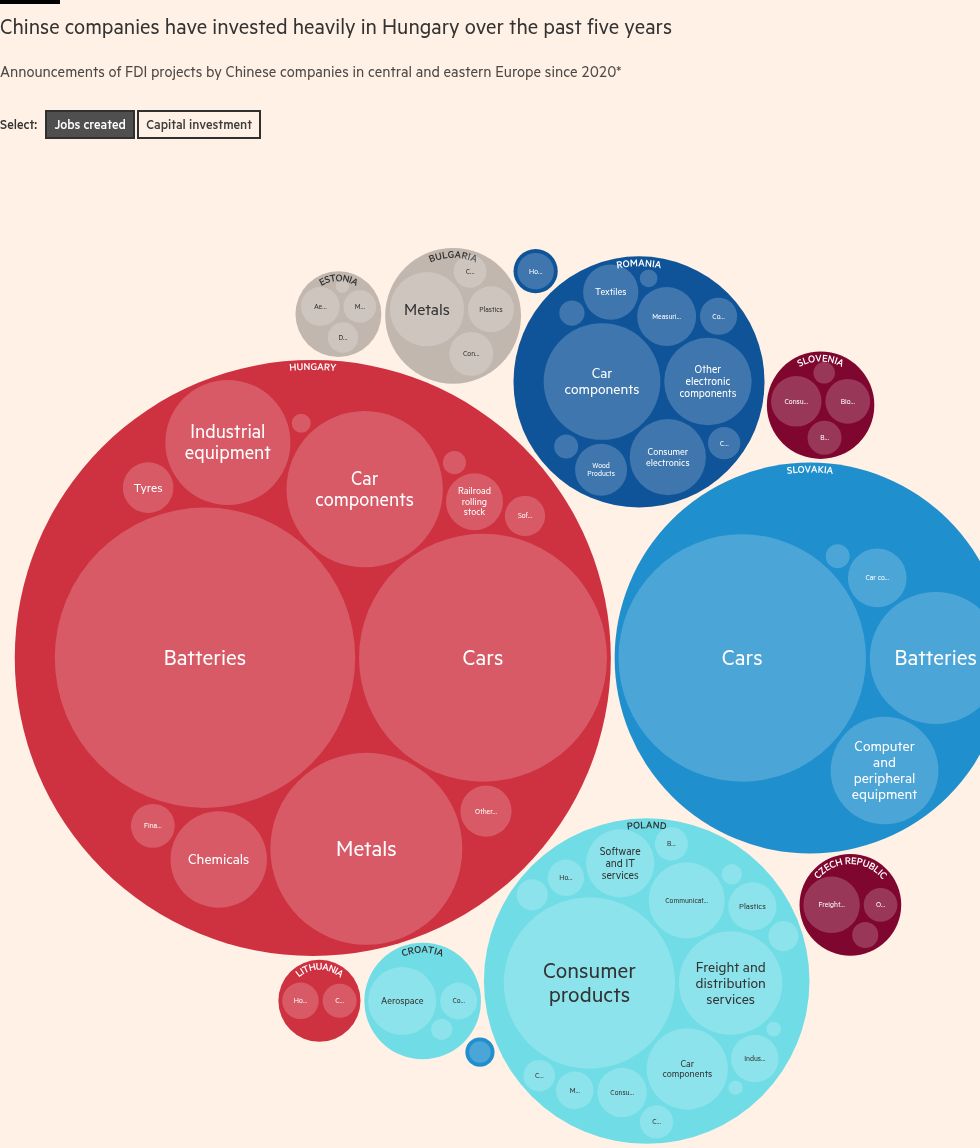

The mile-long plant is part of a wave of Chinese investment that mushroomed across central and eastern Europe immediately after the Covid-19 pandemic, focused on building battery and electric vehicle factories.

But nearly three years after CATL announced the €7.3bn “greenfield” project, weaker than expected EV demand in Europe is forcing a review of its size.

The project’s first phase has increased 20 per cent to 40 gigawatt/hour but two subsequent stages are being “rethought” subject to market demand, officials at the company say. This includes looking into producing technologies other than the lithium-ion batteries the Debrecen plant was designed for.

The move reflects wider forecasts of slowing Chinese investment in new projects in Europe.

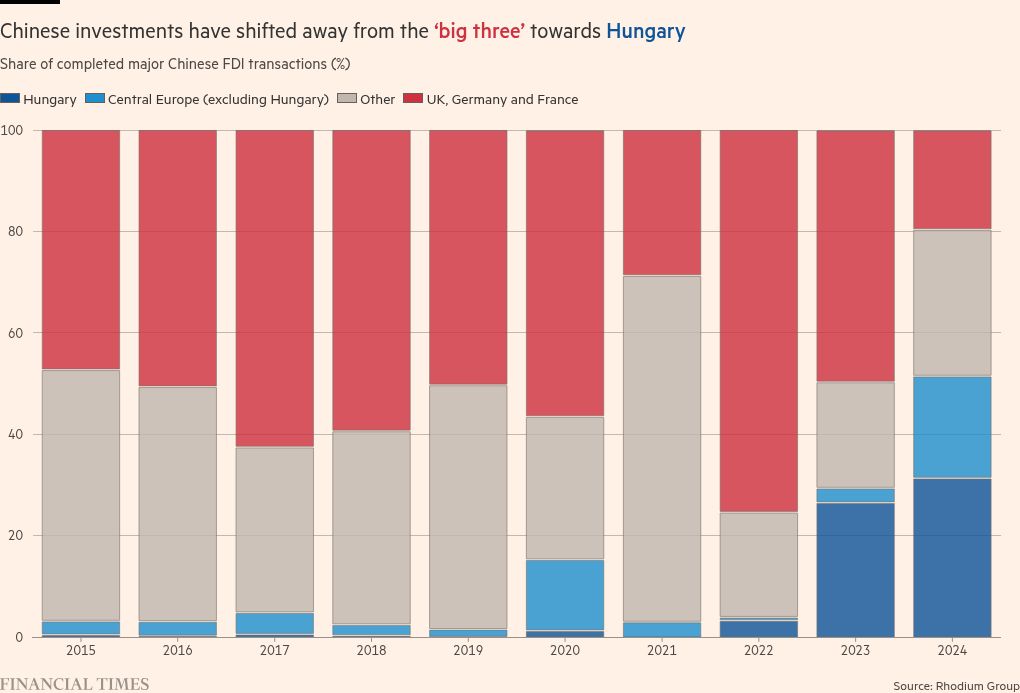

The combination of trade tensions, political strains over China’s support for Russia and Europe’s relatively soft EV market have reduced the case for Chinese investment in the EU, according to Agatha Kratz at consultancy the Rhodium Group.

In the latest sign that geopolitical competition is impacting supply chains and investment decisions, Beijing earlier this month unveiled sweeping export controls on rare earths and critical minerals.

“We’re likely to see a deceleration in the pace of new Chinese greenfield projects in the EU and Europe in general given the political tensions — at the very least 2025 is shaping up to be a ‘pause’ year for investment,” said Kratz, a China specialist.

There was already a “sharp drop” in the value of newly announced Chinese EV projects in Europe in 2024, according to a report by research provider Rhodium and German think-tank the Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics) in May.

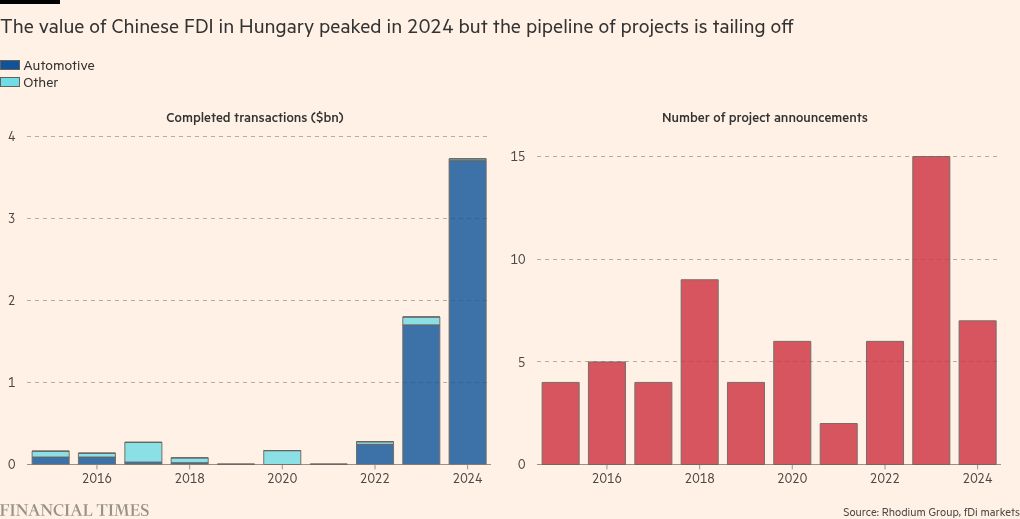

After the pandemic, Hungary was one of the main beneficiaries of Chinese auto investment in Europe, Rhodium data shows. But forward-looking figures from fDi Markets, a Financial Times database, show a drop in the overall number of projects announced in Hungary from 15 in 2023 to just seven last year.

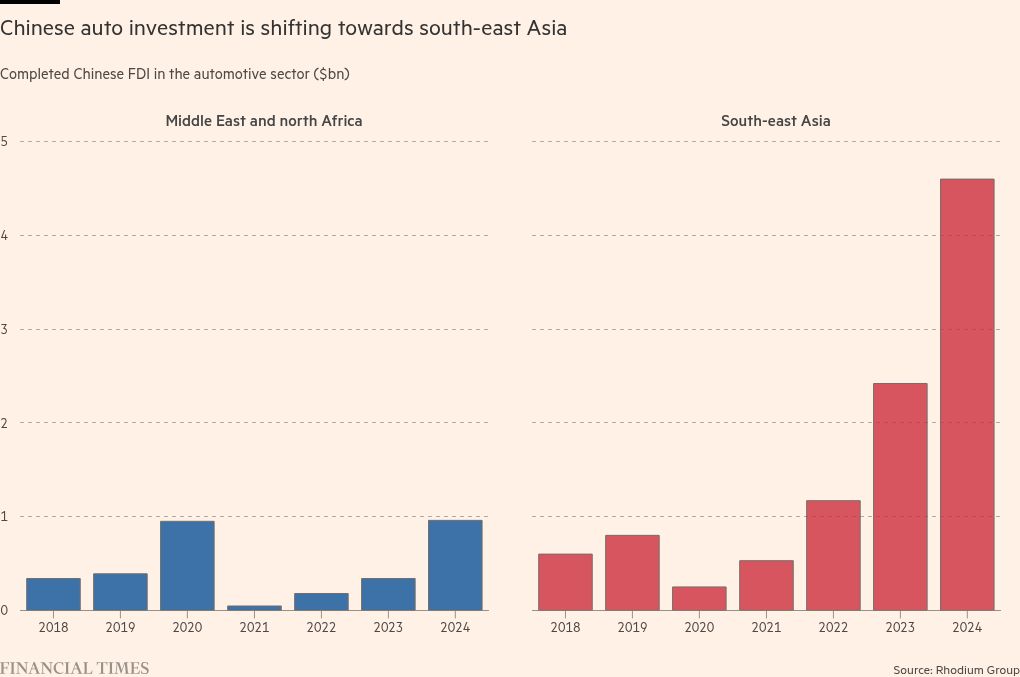

Chinese investment in the car sector has shifted towards south-east Asia to take advantage of faster-growing markets and existing manufacturing and battery plant infrastructure.

There is little sign of Chinese companies investing in other sectors in the EU to compensate, said Andreas Mischer at Merics.

“In 2024, the only significant sector outside automotive for greenfield [projects], was information and communications technology, but that was less than €500mn, only a tenth of the greenfield investment we saw in automotive, so we don’t expect it to be a viable replacement,” he said.

A stand off with Beijing over European demands for Chinese technology transfers as the price of investment is dulling prospects for another upward surge.

Official advice to a meeting of French and German ministers in July argued that in crucial sectors such as batteries — where Europe has struggled to create domestic champions — investment from China ought to be “coupled with technology transfer”.

But CATL’s move to send thousands of workers to build and fit out a €4bn plant in Spain in a joint venture with Stellantis has already raised questions about Chinese companies’ willingness to share industrial knowledge.

“I don’t expect much knowledge sharing or tech transfer to take place,” said Matthias Schmidt, an independent car analyst at Schmidt Automotive Research, noting the irony that western car companies were forced into technology transfer agreements when investing in China in recent decades.

“EU manufacturers in China were forced into local JVs which gave them the skills to produce vehicles. Now the sous chef has opened their own restaurant down the road,” he said.

In a further deterrent, the European Commission has warned it will step up its screening of Chinese investments into Europe, using the foreign subsidy regulation (FSR) that allows Brussels to block companies it believes are unfairly supported by foreign governments.

At the same time, the commission last year imposed tariffs of up to 35 per cent on some Chinese EVs imported to the EU, citing the “unfair subsidisation” of Chinese firms that posed a threat of “economic injury” to domestic carmakers.

Chinese EV makers could get around these by investing in more production facilities within the EU. However, the levies, which do not cover increasingly popular plug-in hybrid EVs, are unlikely to be high enough to drive a big shift, according to Kratz — especially given other risks such as the FSR.

China’s leader Xi Jinping’s support for Russian President Vladimir Putin has also created a more hostile political environment in the EU towards Chinese investment, even if Hungary continues to maintain close relations with Beijing.

Michał Baranowski, Poland’s deputy minister for development and technology, said Poland and other EU member states were now “more clear-eyed” about investments from China and demanding a more equal relationship with Beijing.

“A balanced relationship is about seeing investments from China in terms of technology and knowledge transfer, the kind that China benefited from in the past when it was the Europeans who were investing,” he said.

Grzegorz Kołodko, a former Polish finance minister, added the Donald Trump administration’s hostility towards Beijing would also make EU member states more cautious about accepting future investments from Chinese companies.

US Treasury secretary Scott Bessent has warned that if Beijing introduces its export controls on rare earths, the US and the rest of the world will “have to decouple” from China.

The US president “doesn’t need to say anything, people here just know it [future investments from China] won’t be welcomed by the Americans”, said Kołodko, who authored a book on China’s global expansion.

None of this means that China’s influence will not still be visible in Europe, given the volume of investment announced after the pandemic.

With a sizeable proportion of the workforce for the Debrecen plant coming from China, foreigners are becoming normal in a city that was long almost exclusively Hungarian.

“This industrialisation began with local and regional impact,” said Debrecen’s mayor László Papp. “But by now Debrecen has become a global player in the process.”

Additional reporting Edward White in Shanghai and Alex Irwin-Hunt in London