Hundreds of China’s top political cadres will next week lock themselves away in a Beijing hotel for four days to map out the country’s next five-year plan — the blueprint for everything from the economy and trade to society and culture.

Framed in party speak, China’s five-year plans — the next will be its 15th since 1953 and will run from 2026-2030 — can seem arcane to the outside world.

Often seen as a relic of the command economy, five-year plans were quietly abandoned by Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union and most western democracies prefer to let the economy run according to market forces.

But, analysts say, these plans serve as an important instrument for Beijing to signal its future priorities and stamp its authority on China’s sprawling one-party state.

“This is state capitalism and it relies on industrial policy, so a five-year plan is still useful,” said Larry Hu, chief China economist at Macquarie.

According to Chinese propaganda, the country’s economic success hinges on these plans, which are overseen by President Xi Jinping and a source of legitimacy for the party.

The plans are “a key governance approach of our party . . . contributing to China’s unprecedented miracles of rapid economic growth and long-term social stability”, the Communist party’s magazine, Qiushi quoted Xi as saying last month.

Five-year plans demonstrate “the political advantage of socialism with Chinese characteristics”, Chinese scholar Yang Xuedong wrote in the party’s Global Times nationalist mouthpiece on Sunday.

The next plan, which will officially be released in March, could hardly come at a more volatile moment.

Beijing is trumpeting its achievements in technology and green tech but faces challenges from the US on trade as well as an ageing population and a long property slump that is hurting domestic demand and fuelling deflation.

Despite the difficulty of preparing for such times, economists say the five-year planning process still makes sense for China’s state-run economy.

For the first five-year plan, Mao Zedong took his inspiration from Moscow and, since then, cadres have hashed out ideas in the 61-year-old Jingxi hotel — its boxlike structure reminiscent of Soviet times.

While the first plans were very “quantitative”, laying out specific production targets for heavy industry and agriculture, they became more flexible in the 1980s as China entered its “reform and opening” period of rapid development following the death of Mao.

In 2006, the word “plan”, or jihua, was dropped from the official title and replaced with guihua, which implies something broader and less prescriptive.

“The objectives in the five-year plans are not intended to govern the day-to-day operation of the government agencies. But they still give some sort of guidance to policymakers and government agencies and they also create a sort of narrative around which people can organise their debates,” said Lu Feng, director of the China Macroeconomic Research Center at Peking University.

For China’s private sector, the plans signal where the government will direct state spending or intervention. From a political perspective, the planning process is also important, analysts say.

“The CCP’s five-year plans are much more than simple plans . . . they are bold statements about the nature of political power and its relationship to society,” David Bandurski, director of the China Media Project, wrote in an article on the 14th five-year plan.

Still, the plans have their critics. “In this day and age, probably Beijing has a fairly good handle over macro and micro policy across the chain of command, and so the five-year plan may have an important signal effect, but, in practice, it’s not really needed,” said Frederic Neumann, HSBC chief Asia economist.

Some argue they lead to goal-oriented economic planning that disregards market principles. Targets for annual economic growth, dropped in the 14th plan, can incentivise cadres in local government to sometimes blindly invest to meet the goals.

But Macquarie’s Hu said China can be flexible in its implementation, for example during Covid-19.

“They want to be strategic but, at the same time, they’re going to be tactical as well,” he said. “With the five-year plan guidance is one thing. What’s going to happen in the next five years is another thing. It’s hard to forecast.”

Seven decades of state planning

The Great Leap Forward (1958-1962)

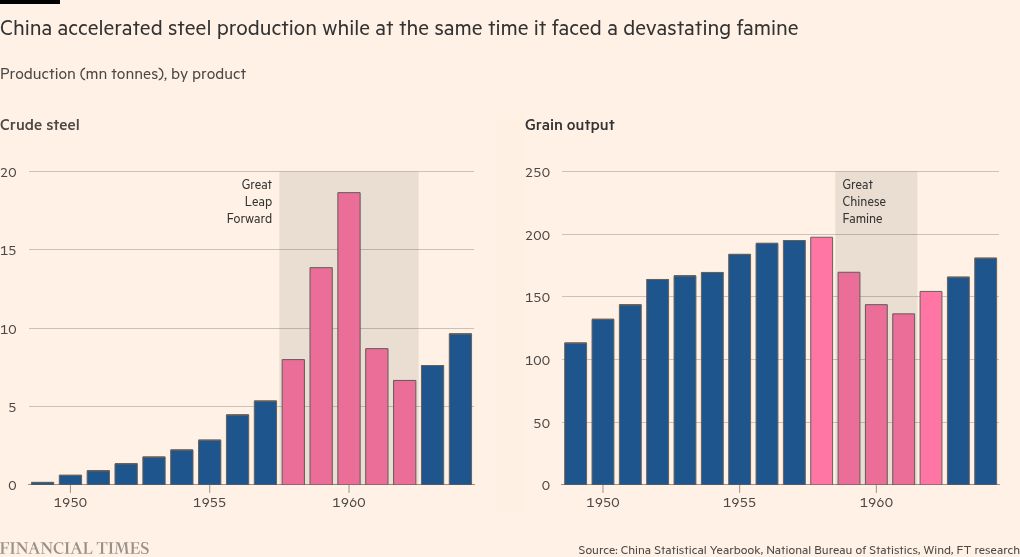

Perhaps China’s most notorious five-year plan was the second (1958-1962), which featured the Great Leap Forward — Mao’s attempt to catapult China into an industrial era using the peasantry as a labour force.

After the relative success of China’s first five-year plan (1953-1957), which increased industrialisation through Soviet-style investment in state-owned factories producing goods such as tractors, machinery and fertilisers, Mao pushed ahead with the collectivisation of farmland.

Officials set overambitious production targets for farming communes to produce not only agricultural goods but also steel. The result was thousands of backyard furnaces inefficiently producing substandard iron and diverting rural workforces from their harvests.

As zealous local officials inflated their grain production figures, the state took a greater share as taxation, leaving the population to starve. Tens of millions of people are estimated to have died in the world’s biggest recorded famine.

Economic transition (1991-2005)

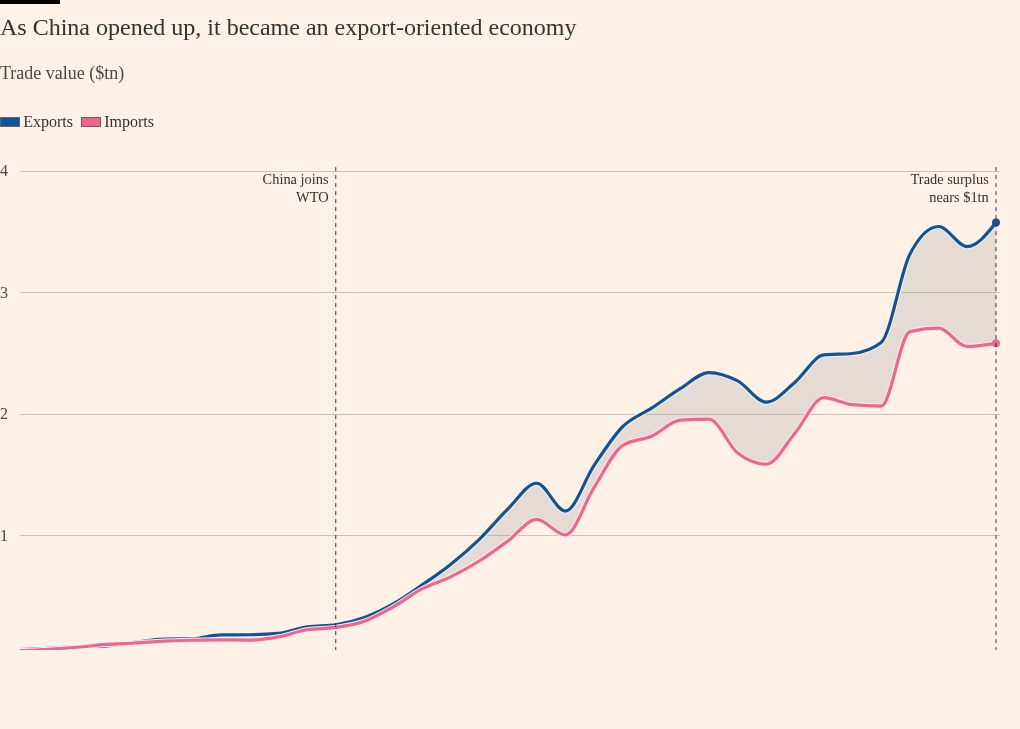

The period spanning the eighth to 10th five-year plans between 1991 and 2005 was one of the most transformative for China’s economy. These plans were led by two economic reformers, the late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and former premier Zhu Rongji.

Partway through the eighth five-year plan (1991-1995), Deng undertook his “Southern Tour” to the prosperous coastal provinces. This reinforced the importance of his market-oriented “reform and opening up” policies following the uncertainty generated by the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. He favoured “allowing some people and regions to get rich first” and opened China further to foreign investment and trade.

During the ninth (1996-2000) and 10th (2001-2005) five-year plans, Zhu transformed the country’s monolithic state-owned enterprises, taking the politically tough step of mass lay-offs and negotiating China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, ushering in its export boom.

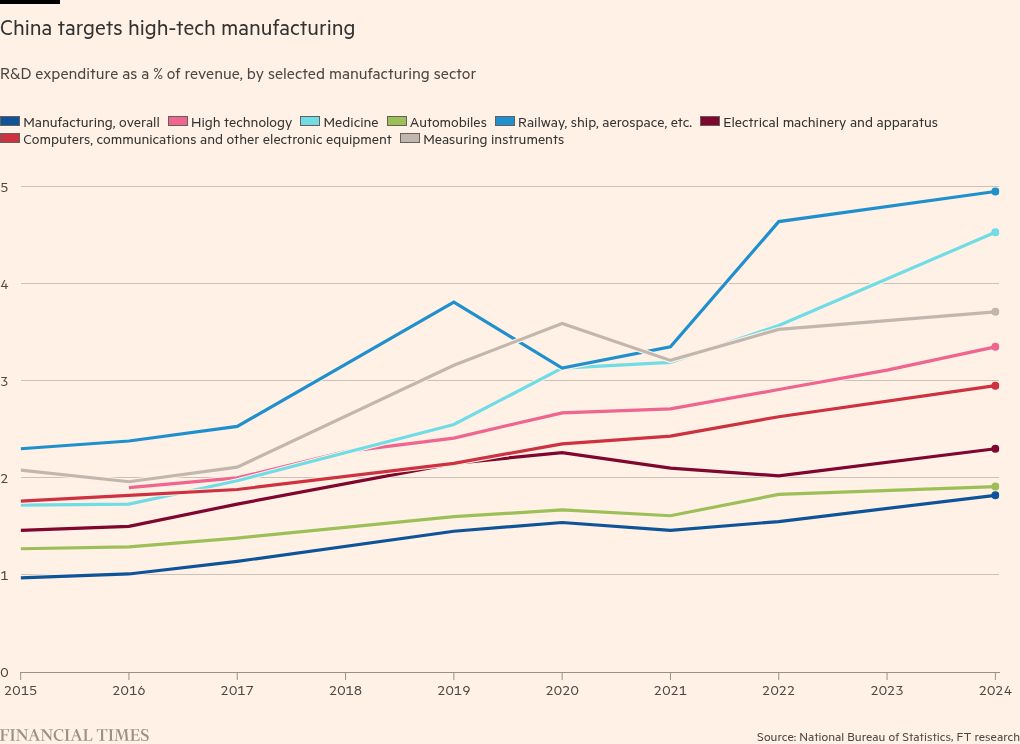

Made in China (2016-2020)

During the 13th five-year plan, Beijing emphasised its “strategy for invigorating China through science and education”, which it had been developing since the ninth plan. This culminated in a subsequent Made in China 2025 scheme.

The Made in China 2025 scheme put the country squarely in competition with advanced economies by setting global market share targets in sectors ranging from telecoms equipment (40 per cent by 2025) to planes (40 per cent by 2025) backed by generous subsidies.

Condemned by western companies and governments as mercantilist, China eventually achieved many of the goals it set for itself.

But the ambition apparent in the Made in China 2025 scheme was one of the triggers of US President Donald Trump’s first trade war.

Productive forces (2021—2030)

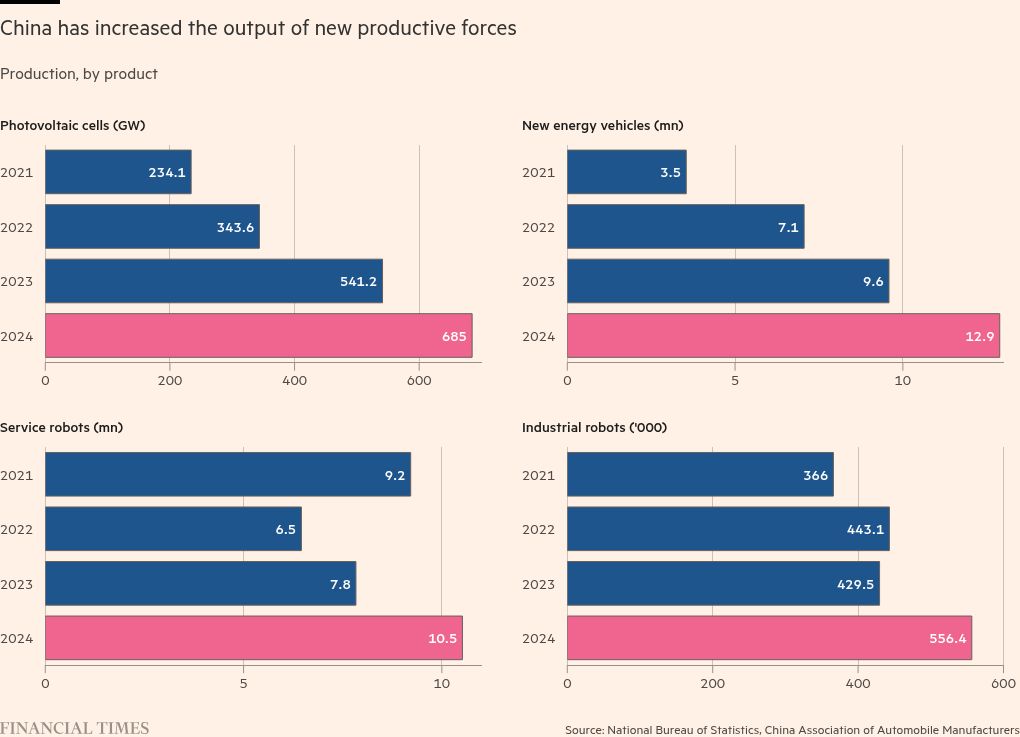

During the 14th five-year plan that finishes this year, China has faced numerous crises ranging from the trade war to the pandemic and a real estate crash.

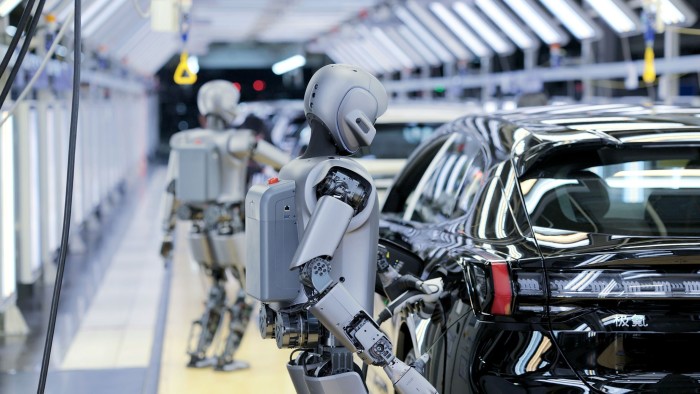

Even in the face of these crises, Beijing has — in line with the plan — emphasised investment in everything from electric vehicles to chips and robots.

While the 14th plan referenced the need to spur domestic demand, a constant refrain in previous plans, the party in practice prefers to support production.

With a declining population, it may in its forthcoming plan finally be forced to spend more on people’s welfare.

“China’s economy recently has been characterised by a pattern of strong supply versus weak demand,” said Peking University’s Lu.

He said if the next plan addressed this issue by, for example, setting a quantitative target to increase the proportion of consumption in GDP, “I think it will be very desirable”.