This article is an on-site version of our Inside Politics newsletter. Subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. If you’re not a subscriber, you can still receive the newsletter free for 30 days

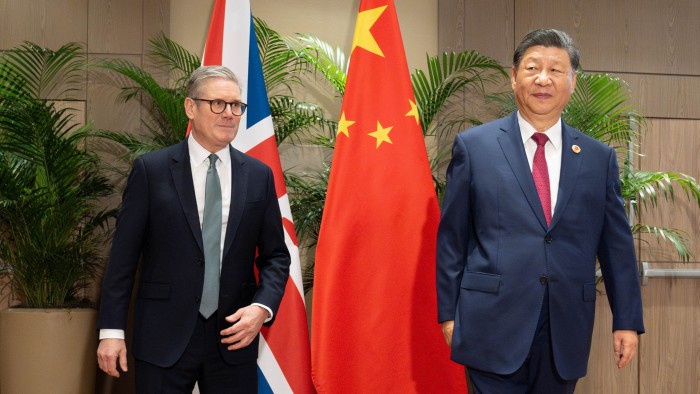

Good morning. One of the few areas of genuine policy continuity between Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer’s governments is in foreign policy in general, and China policy in particular. Sunak wanted to reset the UK-China relationship, but his ability to do so was limited by events and the hawkish turn of his own party.

Starmer’s party is not particularly hawkish, nor is it going to become so any time soon. But events still pose considerable obstacles to his aims, just as they did for Sunak. Indeed, this latest row — over a collapsed alleged China spying case — posed trouble for Sunak when the story first broke back in 2023. Below are some thoughts on what has and hasn’t changed since then.

Inside Politics is edited by Harvey Nriapia today. Follow Stephen on Bluesky and X. Read the previous edition of the newsletter here. Please send gossip, thoughts and feedback to insidepolitics@ft.com

Great walls

“Why did the Labour government decline to provide a witness statement saying that China was a threat to national security at the time of alleged spying offences between 2021 and 2023?” is a question with two really simple answers.

First, the Labour government is trying to repair and strengthen the UK-China relationship, which became much more confrontational and less close from 2016 to 2022. Arranging to meet Xi Jinping with one hand and signing off witness statements saying he is a national security threat with the other would complicate that objective.

Second, Labour would struggle to provide a witness statement saying that the three Conservative governments that ran the country from 2021 to 2023 saw China as a national security threat, because for at least one-third of that time they didn’t. Liz Truss’s 49-day government absolutely did. But the position under Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak’s governments was more equivocal, in large part because of Sunak himself.

Sunak’s attempts as chancellor to arrest and reverse the Tory party’s hawkish turn on China was one reason why in his first, unsuccessful tilt at the premiership in 2022, he only ever got the support of a little over one-third of his colleagues. As prime minister, he exerted considerable time and political capital to repair the UK-China relationship, and had modest success in doing so. But he was thwarted, both by the increasingly Sinosceptic parliamentary Conservative party and by events (as I wrote in this newsletter at the time).

Starmer’s life in parliament is easier because there isn’t a large or particularly committed caucus of China hawks on his backbenches. The Parliamentary Labour party has never been particularly well-endowed with would-be experts on geopolitics. For Labour MPs, being interested in foreign policy usually means one or all of the following: “I am an Atlanticist”, “I, or my constituents, have strong feelings about Israel-Palestine”, “I really like Europe”, or “I worked in international development before I was an MP”. That is still true of the 2024 intake, with some exceptions.

But the political challenge outside the party is greater, because the Conservatives and their supporters in the British press have grown more Sinosceptic in opposition.

Back in the summer of 2022, it was an open secret that Kemi Badenoch’s preference between Sunak and Truss was Sunak, and in the autumn of 2022 she was a decisive and early backer of Sunak over Johnson. It was no secret that Sunak was a China dove! It was only in February of this year that Badenoch was describing herself as a hard-headed “conservative realist”. Now, we have Conservative frontbenchers calling for the government to block planning permission for China’s new super-embassy in London.

That is a constraint that is here to stay, I think. Whoever is in opposition, particularly when they feel very far from power, will be more hawkish on China than they could ever realistically be while being the prime minister of a mid-sized open economy like the UK.

In reality, of course the British government is not going to block the construction of a new embassy, and of course the British government is going to seek foreign direct investment from China. But this government, like Sunak’s, is not going to be able to repair the relationship as much as it would like. Again, this is in part down to events, but also because of the Sinosceptic turn of many in Westminster (even if this time the Sinoscepticism the government must contend with largely comes from outside its party).

Now try this

This week, I mostly listened to the KPop Demon Hunters soundtrack while writing my column.