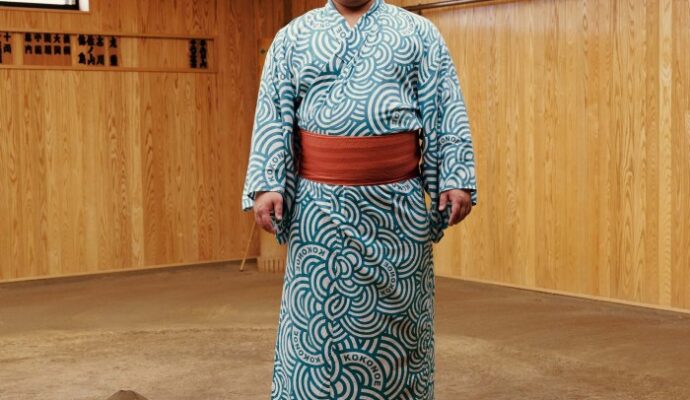

At 6ft 2in, former bodybuilding champion Jiao Qinghua cuts an impressive figure as he peruses the lots on offer at the Shanghai sale of auction house Council. The midsummer sun beams through the Shanghai Grand Theatre’s translucent roof; the plush blue carpets and the 20th-century Chinese ink works on display bake in the heat.

But the avid collector of Modern, contemporary and classical art from China’s eastern Jiangsu province is downbeat. “The economy is declining and the pressure is high. A lot of bosses and entrepreneurs used to dare to buy,” Jiao says when we meet in his hotel by the Shanghai People’s Park the day before the auction. “Now they don’t dare to buy because they have no confidence.”

Jiao is a veteran of the coal industry who buys art with a business partner, another entrepreneur from the same province, though he declines to elaborate on their arrangement. He thinks the once-swaggering mainland Chinese art market has entered a downward spiral — and he doesn’t know when it will recover.

“Before 2015, all segments of the market — no matter if it was painting, porcelain, antiquities, Chinese furniture — they all sold well,” he says. “After 2015, it started to be quite bad, a lot of people’s purchasing power was restricted.” Though the market held up broadly until about 2018, the pandemic dealt a death blow to buyers’ confidence. Not only did sale prices decline, but the number of bogus transactions, in which buyers fail to pay for works successfully bid for at auction shot up, Jiao reckons — and data confirms.

He is touching on an issue that has plagued Chinese auction houses and perplexed western observers for years. In many sales, particularly more expensive ones, buyers fail to pay for works in a timely manner, or at all, says the China Association of Auctioneers. In the year to May 2024, as many as half the lots sold at auction for more than Rmb10mn ($1.4mn) sampled by the association were not paid for by the reporting date, the highest proportion in any year outside the Covid-19 pandemic since at least 2012.

For decades, rapidly expanding ranks of millionaires and billionaires, minted by China’s unprecedented economic boom, dominated global art markets and delivered hefty commissions and big profits for auction houses. But more muted sales prices and those buyers going Awol when the invoice arrives are indicative of a shift in the attitudes of Chinese collectors as the country grapples with the effects of an economic slowdown, greater scrutiny of lavish spending and a sweeping crackdown on corruption.

Despite a spike in sales in late 2022 and early 2023 after China’s strict pandemic controls were loosened, spending on items at auction has since faltered. In 2024, auction sales in mainland China slumped 38 per cent year on year and the country fell to third in the ranking of global art markets, according to the Art Basel/UBS Art Market Report. Sales at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips in Hong Kong fell 30 per cent.

The slowdown has left collectors, advisers and auction houses alike wondering whether the juggernaut of Chinese wealth that has propelled the market for the past two decades is slowing down — and why so many winning bidders don’t end up paying.

It was not always like this. In the mid-2010s, the new class of wealthy individuals stunned the auction world with a series of extravagant trophy purchases.

In 2013, Wang Jianlin, chair of property conglomerate Dalian Wanda Group and then China’s richest man, paid $28.2mn for Pablo Picasso’s “Claude et Paloma” at a Christie’s auction in New York. In 2015, Liu Yiqian, a former cab driver turned billionaire stock trader, spent $170.4mn on Amedeo Modigliani’s “Nu Couché”, paying for it with multiple swipes of his American Express. A year earlier, he had used his Amex to purchase a $36mn Ming dynasty porcelain tea cup. And then he drank from it.

The dominance of Chinese wealth at global auctions was a reversal, says Patti Wong, former Asia and international chair at Sotheby’s, who estimates that in the 1990s Asian buyers made up just a fraction of sales at the auction house.

“It was like nothing . . . regionally they were talking about maybe 5 per cent of the total turnover,” says Wong, who helped transform Sotheby’s Hong Kong office into one of its most important hubs over her nearly 20-year tenure as Asia chair. “And by the time coming up to Covid, [for] Sotheby’s, like a third of the business was happening in Hong Kong.”

While characters such as Liu attracted global notoriety for their purchases of Modern and Impressionist works, Chinese buyers had already started cutting their teeth buying ceramics and Chinese artworks in the early 2000s, Wong says.

By 2011, they were so active that 10 of the 15 most sought-after artists globally were of Chinese origin, with painters Zhang Daqian and Qi Baishi both surpassing Picasso’s record for the largest annual sales value, according to data from Artprice. But when China’s new tycoons turned their attentions to blue-chip western art, they felt they were “playing a catching-up game”, Wong says, sipping coffee at the Hong Kong offices of the art advisory business she now runs.

“They came in right at the top. This is a generation of buyers who had made money . . . over a very short time and were eager. So first was the national pride of buying your own national objects back. But later it was actually trophy-buying and wanting to make a mark on the international scene.”

That hunger also made them competitive. “They liked that excitement of playing in the big field: ‘Now I’m no longer trying to beat another Chinese guy, but I’m trying to get the trophy.’ They could name all those people because they know they’ve read [about] the big collections, [Microsoft co-founder] Paul Allen and so on.”

And while auction sales in Hong Kong and from Chinese buyers began to moderate after around 2015, Wong thinks that Asian buyers bid for at least half of the most expensive lots sold each year globally right up until the pandemic: “It was exponential.”

Undeterred by the suffocating heat in the Starry Sky banquet hall, the staff of Shanghai Council, in black tie and smart dresses, make quick work of their annual spring auction. Heads in the packed audience flick from left to right as they track intense bouts of bidding between in-room buyers and the Council staff manning telephones, who sit below large prints of Chinese 20th-century masterpieces.

Several items, including “Double Happiness Arrives at the Door” (1947), an ink painting of magpies perched on wintry branches by Xu Beihong, and “Subdistrict Office Canteen” (1960), a collectively-painted socialist ink-work led by Fu Baoshi and Ya Ming, sell for well above their upper estimates. “Autumn Heights of Qixia” (1992), a vermilion-infused landscape by Wei Zixi, sells for Rmb1.92mn, more than twice its upper estimate.

All in, the Chinese painting and calligraphy auction lasts more than three hours and is the most significant part of a spring sale series “filled with passion and energy”, according to a Shanghai Council statement. “Many treasures not only achieved a leap in value, but also shone with their own unique brilliance.”

But shortly after, the cracks begin to show. While many works sold for more than Council had expected, the majority of lots went for well under the value they might have fetched in years past, as several collectors and art market insiders who spoke to the Financial Times point out.

The catalogue suggests this. Next to Xu Beihong’s magpies, which sold for Rmb2.4mn, is an inset of his “Four Happinesses”, a visually similar work which sold for Rmb28.75mn in 2011. A lot of a rooster by the same artist, which sells for Rmb850,000, is featured next to another that sold for more than Rmb10mn previously.

Jiao, who strides into the auction about halfway through, says later that he bid on several works, but did not purchase any. “Many important collectors are still reluctant to sell their valuable works and there is a strong sense of market caution,” he says.

The pull of Chinese wealth remained so strong in the pandemic years that the world’s largest auction houses — Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Philips and Bonhams — all worked on plans to open bigger, and considerably swisher, headquarters in Hong Kong.

The proximity of the city, a semi-autonomous territory off the coast of south China, to the mainland makes it a convenient hub for Chinese buyers to source their next big purchase. But unlike mainland China, it has a freely convertible currency pegged to the US dollar, no capital controls and few restrictions on the import or export of cultural heritage, making it a natural spot for Chinese and international buyers to tussle over Chinese and western art alike.

The new auction house sites included Christie’s 50,000 sq ft base in the Henderson building, one of the city’s newest and most prominent developments and, Sotheby’s two-storey retail “maison” in the heart of the central business district. Both companies said the sites underlined their commitment to the greater China market.

But when the new hubs began to open, relying on Chinese buyers started to look like a badly timed bet. Asian, predominantly Chinese, buyers’ contribution to global auction sales at Christie’s had fallen to 21 per cent by the time it opened its new Hong Kong HQ, down from 39 per cent when it first announced its plan in 2021. Sotheby’s, meanwhile, had suffered lay-offs and cutbacks.

The slowdown echoed a downturn in the Chinese economy as a whole. Years of strict lockdowns and pandemic controls hammered the country’s once-breakneck growth and ruined consumer confidence. A years-long crisis in the country’s massive property sector — for decades a key driver of rising wealth — left even the wealthy questioning the sustainability of China’s economic rise.

Clare McAndrew, founder of Arts Economics, which produces the Art Basel/UBS Art Market Report, says that while there was an initial burst of “revenge spending” emanating from Chinese buyers in early 2023, as the country unwound its years of strict Covid controls, that had already begun to peter out by the second half of the year.

Last year, economic weakness continued to hamper Chinese buyers, with sales in both Hong Kong and mainland China dropping sharply, partly because few consignors were willing to sell into what they saw as a falling market. Now, uncertainty over the market’s prospects remains, says McAndrew. “All the issues that we’ve had are still around . . . Art is not immune.”

Elsewhere in the Chinese auction sector, some collectors are more upbeat. Xie Wenwei, who owns Guangzhou-based antiques dealer Man Po Chai, says now is the time to buy. Chinese antiquities have been one of the areas hardest hit by a slowdown in luxury and big-ticket spending in the country, partly because pieces within China generally cannot be bought for export, meaning the domestic market is closely tied to the vicissitudes of the Chinese economy. After the long boom, sales began to slump from 2018 and have been muted ever since.

Xie acknowledges the challenges. “The economy these past few years has been a bit on the decline . . . There are fewer buyers with less spending power,” he says, sipping tea surrounded by Ming and Qing dynasty ceramics in his office in Guangzhou.

In Hong Kong too, auction sales have been affected by tighter enforcement of capital controls. “If your money is onshore it will be very difficult . . . It will definitely affect business at Hong Kong auction houses. ‘‘Small payments” of several million renminbi will generally be OK; anything in the tens to hundreds of millions would be ‘‘very difficult’’, he added. But, he says, with the Chinese government now actively trying to promote its cultural industries, things could be about to turn around. “Speaking optimistically, the economy could recover next year,” he says. Chuckling, he adds: “Time to stock up.”

While Jiao agrees that prices have fallen enough to warrant bargains, he remains frustrated by the issue of non-payment, which he links to the overall performance of the Chinese economy. Figures from the Art Basel/UBS report show that the rate of uncompleted transactions were the inverse of sales: they shot up during the pandemic, then improved briefly in the 2022-23 post-Covid bump, before rising sharply again in the 12 months to May last year.

“There are lots of non-transacted works now,” says Jiao. “All people in the auction industry have experienced this.”

Jiao himself ran into the problem in April, when a work he sold at auction in Beijing was never paid for, so he will have to sell the work again elsewhere, likely for a much lower sum.

Auction industry experts and participants are perplexed as to why the level of unpaid works remains so high, and why auction houses within China continue to deal with clients who fail to make payments. None of the major Chinese auction houses contacted by the Financial Times for this story offered comment on the issue.

Wong, the former Sotheby’s chair, suggests that, for some in the industry, registering a few bogus sales can help to create hype for an artist. Others say that China’s legal environment makes it difficult and time-consuming to sue buyers who don’t cough up. China’s smaller auction houses, meanwhile, are reluctant to disclose when a sale falls through for fear of harming overall market sentiment.

In other cases, auction houses may agree to offer flexible or extended payment terms to help entice potential buyers, but in times of economic hardship some buyers can get cold feet, go bankrupt or do more research on the work that leads them to change their minds before completing payment.

While the issue of non-payment is not restricted to mainland China, western auction houses have much stricter requirements for new bidders and a significantly lower rate of incomplete transactions. Potential buyers who do not have a record generally have to pay a hefty deposit to bid on the most expensive lots or provide proof of adequate funds to purchase items they have registered for, according to current and former auction executives and collectors.

Nonetheless, they too can run into issues accepting bids from mainland Chinese buyers. Beijing enforces strict capital controls that limit the amount of money citizens can take out of the country to $50,000 per year. Industry figures also said getting money out of China to participate at western auctions offshore had become harder since about 2018. Workarounds such as paying for works with bank cards, so that regulators viewed transactions as discretionary spending rather than currency transfers, had been clamped down on.

“We are very strict on this: the last thing we want is that something is sold but it’s not being paid,” said a former senior auction executive in Hong Kong, who added that new bidders on big-ticket lots had to prove their funds by paying offshore deposits.

For Jiao, the driver is simpler: “A lot of people don’t pay when the economy isn’t good. They don’t want to take their money out of their pockets.” Although he sees the current climate as an opportunity to snap up bargains, he is gloomy about the long term. “We don’t know where the bottom is.”