Chinese stocks are outpacing global peers by the widest margin in eight years, in a sign that policymakers’ efforts to revive the market are bearing fruit even as many foreign investors hesitate to return.

The MSCI China index has surged 35 per cent this year, compared with a 14 per cent gain in the MSCI World index of developed market stocks, the largest margin of outperformance since 2017.

This year’s rally comes after many global fund managers last year branded China — whose stock market had been in near-constant decline since peaking in early 2021 — “uninvestable”, following a government crackdown on the private sector and a long-running real estate crisis.

However, Beijing has been pushing to improve corporate governance at state-owned enterprises and private companies, and has launched huge monetary and fiscal stimulus, including measures for financing share buybacks.

Investors say these measures — together with a drive to increase the insurance sector’s equity purchases and concerted buying by the so-called national team of state institutions — are starting to turn the stock market into a viable alternative to property.

“Part of the reason money went into real estate was the stock market was viewed a little bit like Macau,” said Brendan Ahern, chief investment officer at KraneShares, an exchange traded fund provider with products investing in China. He was referring to the tendency for locals to view the market as a casino rather than a place to allocate long-term savings.

“If you can make the stock market an appealing source of returns, it would arguably divert money from going back into real estate. That makes sense for the government,” he added.

Mark Headley, chair of Matthews Asia, an investment manager, said the government viewed the reforms as necessary to help its capital markets compete with the US.

“The Chinese government and the Chinese people have finally recognised that just owning a fifth apartment somewhere is not the perfect savings plan,” he said.

China’s stock market is small relative to its economy. The country accounted for 16.8 per cent of global GDP in 2024 but just 10.3 per cent of global stock market capitalisation, according to the World Bank. China accounts for only 3.35 per cent of MSCI’s all-country world index.

However, the number and quality of Chinese stocks have improved significantly over time, said Archie Hart, a portfolio manager at Ninety One in London. Of the more than 5,000 companies listed in mainland China, 2,504 have a market capitalisation of more than $1bn, according to data provider Wind.

“I look at it on a very long-term perspective. Thirty years ago your choices were state-owned,” Hart said. “Today you’ve got a fantastic choice of ecommerce companies, tech, manufacturing companies, consumer brands.”

Regulators have stepped up their efforts to improve stock market returns and corporate governance at China’s state-owned companies. Measures include tying managers’ key performance indicators to share price performance and return on equity.

When a stock market rout at the start of last year worsened, Beijing brought in Wu Qing, nicknamed the “broker butcher”, as head of the country’s securities regulator in a move to ease volatility and stabilise the market.

In a speech this year, he referred to foreign investors as “important participants in China’s capital market” and said he would accelerate measures to open up capital markets to the outside world.

In September last year, the China Securities Regulatory Commission encouraged listed companies “to lawfully and compliantly use M&A, equity incentives, cash dividends, investor relations management, information disclosure and share repurchases to elevate their investment value”.

“There’s a big effort by the regulators in these agencies to make the mainland Chinese companies credible companies for international investors,” said Amar Gill, secretary-general of the Asia Corporate Governance Association.

But some in the industry see resistance within parts of government to market reforms that could diminish the state’s influence over corporate decision making.

“The tension, I would say, is between the agencies, the regulators and the party,” Gill said. “The party is still wanting to have control of state-owned enterprises and to some extent private companies as well, while the regulators are looking to see how they can make these companies focus on shareholder value.”

China’s outperformance this year comes as global investors seek to diversify their portfolios, which are often highly concentrated in the US.

However, US-China tensions and macroeconomic uncertainty are deterring many from reconsidering mainland stocks, even as Hong Kong proves attractive and other Asian markets such as South Korea and Japan are widely seen as less risky.

“To attract both domestic and foreign investors is going to take two to three years of steady returns,” said Headley.

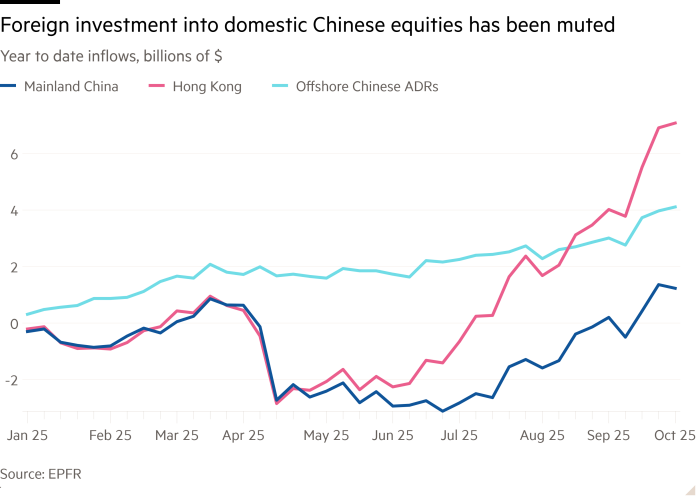

Foreign flows to China’s mainland market have been muted this year, according to EPFR data tracking ETFs and mutual funds domiciled outside China. Mainland stocks received just $1.2bn of net foreign investment this year.

Some foreign investors remain unconvinced that China’s reforms have gone far enough, with many seeing recent initiatives as signs that Beijing wants to increase its control over companies and markets.

“There is still a huge sceptical slant” in western countries towards China, said the ACGA’s Gill.

Ryan Manuel, managing director of Bilby, which analyses government policy using artificial intelligence, said there was still tension between reforming China’s capital markets and the government’s fixation on controlling strategically vital sectors.

“Industrial policy muscles are stronger than capital markets reform muscles,” said Manuel.

Nevertheless, for Chinese investors, the options are limited. “Where else are you going to put money in China with the real estate market being dead?” Manuel added.

Additional reporting by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong