Welcome to Trade Secrets. Not for the first time, writing about trade, incredible though President Donald Trump’s policies are, feels slightly beside the point with the extraordinary violations of law and human rights going on in the US. I wish I hadn’t been right when I wrote this back in February, but it looks like I was. Anyway, to keep to my lane, today I look at why the farmers’ revolt that free-traders and trading partners are hoping will restrain Trump’s tariffs didn’t happen before, and won’t happen now. Charted Waters, where I look at the data behind world trade, is on shrimp tariffs.

Get in touch. Email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

Soyanara, exports

Soyanara. Get it? Not sayonara, soyanara. Soya. Oh, please yourselves.

No one ever accused Trump of joined-up policymaking, and there’s an entertaining tangled-web subplot to the global trade drama right now. American soyabean farmers are complaining that Trump’s trade war is blocking them from Chinese markets. All the while, the US president funds their Argentine rivals to export to China instead.

This is a bit of a simplification, obviously. But the $20bn rescue credit line the US is offering to Trump’s ideological Argentine soulmate President Javier Milei — which I wrote about last week — must grate a bit. Argentine farmers are merrily filling the gap in the Chinese market opened up by China’s boycott of US farmers, which was a display of leverage ahead of the upcoming meeting between Trump and President Xi Jinping.

Soyabean growers are not the only ones. Just as during his first term, retaliation by foreign trading partners (in this case, China) against US tariffs has been broadly aimed at US agriculture.

So have farmers been betrayed by blowback from a trade war they never voted for? Is a revolt of farmers carrying pitchforks (or, these days, riding combine harvesters costing a chunky $800,000 new, plus tax) about to force Trump to drop his tariff campaign? And will farmers and farm counties turn against Trump? The answers are no, no and no — and the administration knows it.

Any farmer who genuinely didn’t see tariffs on their exports coming should probably have their eyesight checked out before operating agricultural machinery. Trump started a trade war in his first term and the retaliation from China and others hurt farmers, despite the $23bn bailout he gave them. Yet, as calculations by the news service Investigate Midwest show, farm counties, where Trump won more than 70 per cent of the vote in 2016, voted for him in even larger numbers in 2020. And despite his promising a far bigger trade war to come, those voters swung yet further towards him in 2024. Should Trump fulfil his unconstitutional wish to go for a third term, whether or not he bothers with the formality of an election, they’ll surely still be behind him.

There are two obvious reasons for this electoral fidelity. First, the past and future federal handouts to soften the tariff blow. (If there’s one thing American farmers excel at, it’s milking the federal government.) Second, culture war issues, which ensure voters in rural states support Republicans even when it’s manifestly not in their economic interest to do so.

Yet a third factor, perhaps less understood, is that many US farmers are so rich and diversified that the tariffs won’t hurt them all that much. As Monica Potts describes well in the New Republic, farmers tend to be very well-off — the clichéd small family farm scratching a living has largely disappeared — and make much of their income from non-farm activities. The tax breaks they get from farming land, their lower personal and estate (inheritance) taxes, and weaker environmental and labour protections are enough to keep them voting for Trump.

Vengeance in vain

This underlines something that I’ve been arguing for a while: the old trading partners’ retaliation manual of hitting US exports from politically sensitive states is less effective than it used to be.

For one, the usual conduit for that pressure is influential members of congress who take their complaints to the White House. But Republicans on the Hill are terrified of Trump. As it happens, Louisiana, the state of US House Speaker Mike Johnson, is a leading soyabean producer, which is why Brussels and Beijing targeted US exports of the legume for retaliatory tariffs. I think we can safely say that, even if Johnson has complained, Trump doesn’t care.

Second, it’s not clear that voters actually shift in response to trade-related losses. I’ve mentioned this before, but one of the most startling studies of Trump’s first term shows that areas where people lost income and jobs from his trade war swung towards him in the 2020 election.

US farmers genuinely believe they’re hard done by in the world trading system, their lavish subsidies not being enough to console them for their restricted foreign market access. Seeing Trump stick it to foreigners presumably pushes some of those resentment buttons, even if it affects their businesses. Sounds crazy to me, too. But the US president’s trade policy long ago unmoored itself from the firm ground of economic sense, and few of his supporters seem to have much interest in pulling it back.

Charted waters

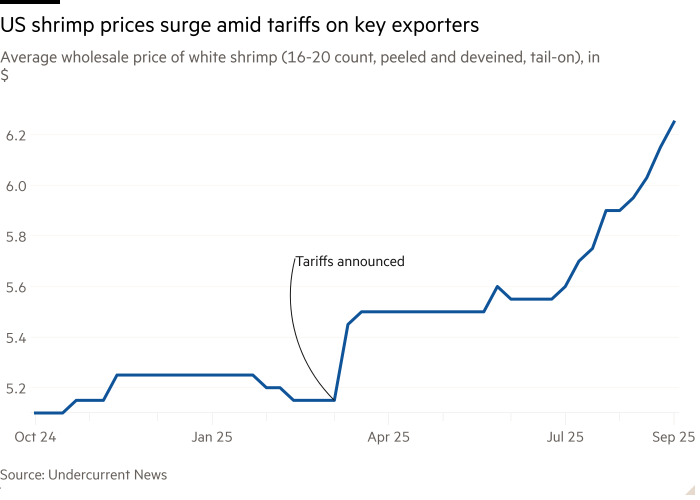

Shrimp prices have shot higher in the US, one of a number of niche exports from Asia to suffer from Trump’s trade policy. His tariffs are doing more to damage crustacean sales than did the legendary turtle-friendly fishing net requirements that touched off a big trade dispute.

Trade links

The South China Morning Post looks at the economic weapons the EU can use against China.

The US ambassador to the EU tells the Financial Times he wants Brussels either to prove its tech rules don’t discriminate against American companies or to fix them.

The Wall Street Journal looks at the difficulties Trump will have in using tariffs to try to onshore pharmaceutical production.

Think-tank Merics examines China’s export controls on rare earths and their impact on global supply chains.

A commentary for the libertarian Cato Institute says that repealing the tariffs soon to be ruled on by the US Supreme Court will not in fact destroy the federal public finances.

Trade Secrets is edited by Harvey Nriapia