One of the fun bits of my job at the FT is when I occasionally co-host our economics podcast, The Economics Show. For me, the task largely involves having a fascinating and enjoyable conversation with a very knowledgeable expert, while my brilliant colleagues work behind the scenes to make it all happen and ensure the product sounds as good as my raw material allows. Thanks to all of them.

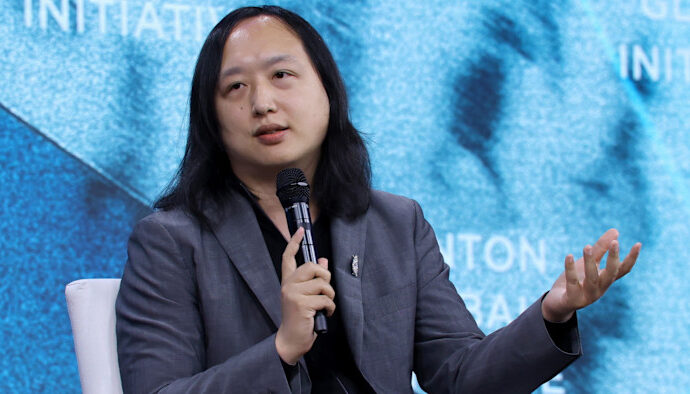

Yesterday, The Economics Show published my conversation with Michael Pettis, an expert on the Chinese economy well known to many Free Lunch readers. I encourage you to listen to it here — come for the discussion about China’s involution challenge, stay for the Chinese indie rock recommendations. If you prefer text, the transcript is available too. In today’s newsletter, I want to pick up on some of the themes we discussed and point out some of the big questions they raise for those of us who are trying to understand the Chinese economy and its role in the world.

I started by asking Pettis what he thinks outsiders tend to get wrong about China. (Actually, I started by asking him about the record label he set up, but you can listen to the interview to hear about that.) I was struck by his answer that when he moved to China more than 20 years ago, and even today,

. . . there was a sense that China was so exceptional, so unique, that there’s really nothing to learn from the experiences of other countries, and that turned out to be completely wrong. And so I think it’s important and very helpful to put China within a historical context. Other countries have had similar growth models, and many of the problems that we’ve already seen are starting to emerge here.

Pettis traced such growth models back to “the so-called American system of the 1830s” and later the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. The key feature of this model is that, rather than importing net foreign capital (by running a trade deficit) to grow, it funds investments entirely from very high levels of domestic savings, which means repressed consumption. But “repressed” here means relative to what it could be; it does not mean consumption does not grow.

From the 1990s, China excelled at this model, with incomes rising very fast but not as fast as the economy as a whole was growing, so “by definition, your savings rates are going up”. But the bigger point is that self-funded high-investment growth is far from unprecedented in history.

This raises several intriguing questions. One is how standard economic policy advice came to have, as far as I can judge, a bit of a blind spot to this development model. That advice has tended to be for poor countries to do what it takes to attract capital from abroad (including from China). And yet it is clearly possible to succeed on the back of your own savings — though China, as I mention in the interview, had the advantage of huge scale and a fast-liberalising global economy to trade with.

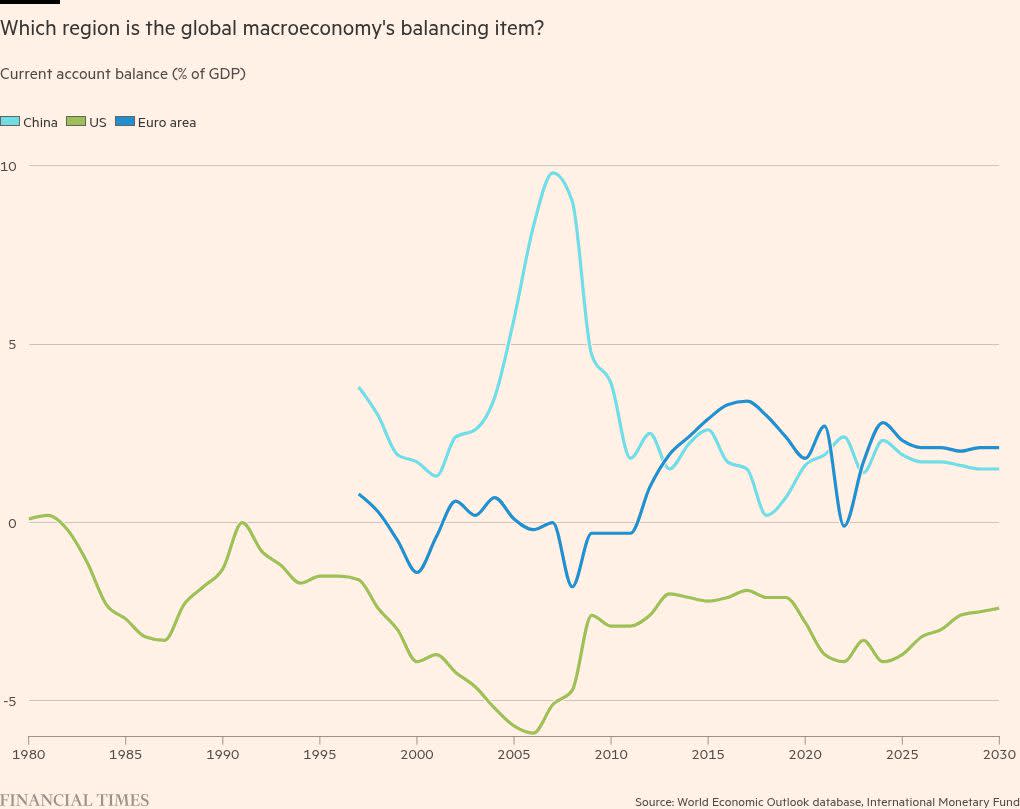

But the main upshot is that running a net surplus (with savings even higher than investment) is a very deeply rooted aspect of Chinese development. And while a shift towards faster domestic consumption growth is theoretically possible, Pettis thinks the historical record is not promising.

That leads to another question. Since Pettis often seems to say that Chinese policies have caused the decline of manufacturing in the US, I asked him: Is Donald Trump right? Pettis’s answer:

I think he is a response to a real problem . . . if the structure of my economy requires that my production grow faster than my consumption and we trade openly among each other, then you have no choice but for your consumption to grow faster than your production.

Free Lunch readers will know that I am sceptical about the “you have no choice” part of this. Although Pettis and I agreed to disagree beyond a certain point, we both accepted this paraphrase I offered of his argument:

If one part of the global economic system uses state intervention and policy tools actively, whereas another follows a laissez-faire approach to the economy, the latter is more likely to become the balancing item for the decisions made by the former than the other way around.

Then the question — and possible disagreement — centres on how much those other countries need to follow a laissez-faire approach, which is a political economy question as much as an economic policy one. Here, I think I am much more optimistic than Pettis, in particular over whether it is necessary to try to undo the large surpluses and deficits at all, which depends a lot on whether the deficit countries’ extra spending power can be turned into additional investment rather than just extra (credit-funded) consumption. Free Lunch readers will no doubt have opinions about this, which we would be keen to hear.

I have two more takeaways from this interview. One is the importance of not conflating the aggregate macroeconomic picture — overall deficits and surpluses — and what goes on in specific sectors. In the interview, we discuss how Chinese policy has targeted three big sectors in less than 20 years to drive growth: infrastructure, housing construction and now green technology such as electric vehicles. In the Chinese growth model (or the “American system” if you like), it seems hard to avoid the temptation to place the entire macroeconomic burden on very narrow sectoral shoulders. The result is “involution” — the process where so many resources are put behind one sector that it runs into inefficiencies, wasted investment, and lossmaking production. The price war on EVs is the latest instance of this, but so were the housing bubble collapse and infrastructure spree before that. (Involution is “a new word for an old problem”, says Pettis.)

There’s a lesson here for how western observers and policymakers react, I think. Don’t confuse the part for the whole: the huge growth in Chinese EV and battery production, for example, is not the same phenomenon as the overall macroeconomic balance, even though they are related. The problems should be diagnosed separately, and separate policies should be developed to address them where necessary. Too much European discourse, in particular, throws everything into a single conceptual bucket of “overcapacity”. Look for the exceptions, such as this recent policy brief from the Kiel Institute, which takes an exemplary sectoral approach.

All of which leads me to a fourth and final point. China’s savings-funded development policies have clearly produced some extraordinary sectoral production leaps. (The Kiel briefing linked to above cites industrial policy measures adding up to 2 per cent of GDP, which is multiples of what western governments spend.) This has led other countries to wonder if they need to replicate, if not the overall model, then the big push of resources in narrow directions. The US is already doing this under the aegis of Big Tech companies getting ready to invest trillions of dollars in artificial intelligence-related infrastructure. The EU, meanwhile, is struggling to fund investment needs that Mario Draghi estimates will cost similar amounts.

But what if China has taken all of this too far? Listening to Pettis, there is reason to think every sectoral wave has ultimately led to big net losses.

. . . when you start overinvesting beyond your capacity to absorb it productively, then you’re generating advances in technology, you’re generating great production, great infrastructure, whatever you like, but it’s no longer economically viable . . . if you are losing money on advanced technology, you’re contributing your advances to the world, and the world really will benefit from Chinese technology, but it’s not clear that you will benefit. And I think that’s the problem where we are in China. The technology is great. It’s just not clear, once you remove the enormous amounts of subsidies, that these are actually value-creating for the economy, right?

Big questions — for China, for western policymakers and for Free Lunch readers. I would love to hear your thoughts; email us at freelunch@ft.com.

Other readables

● Has Ursula von der Leyen lost the European public with her excessively timid approach to Donald Trump?

● US politicians are more likely to do their donors’ bidding immediately after natural disasters.

● Are US companies mainly adopting AI out of fear of missing out? FT colleagues find they can’t explain the upsides.

● The European Commission is (finally) telling Europe’s shopkeepers how they would benefit from a digital euro.

● Economic warfare: how Israel is undermining monetary circulation in the West Bank.