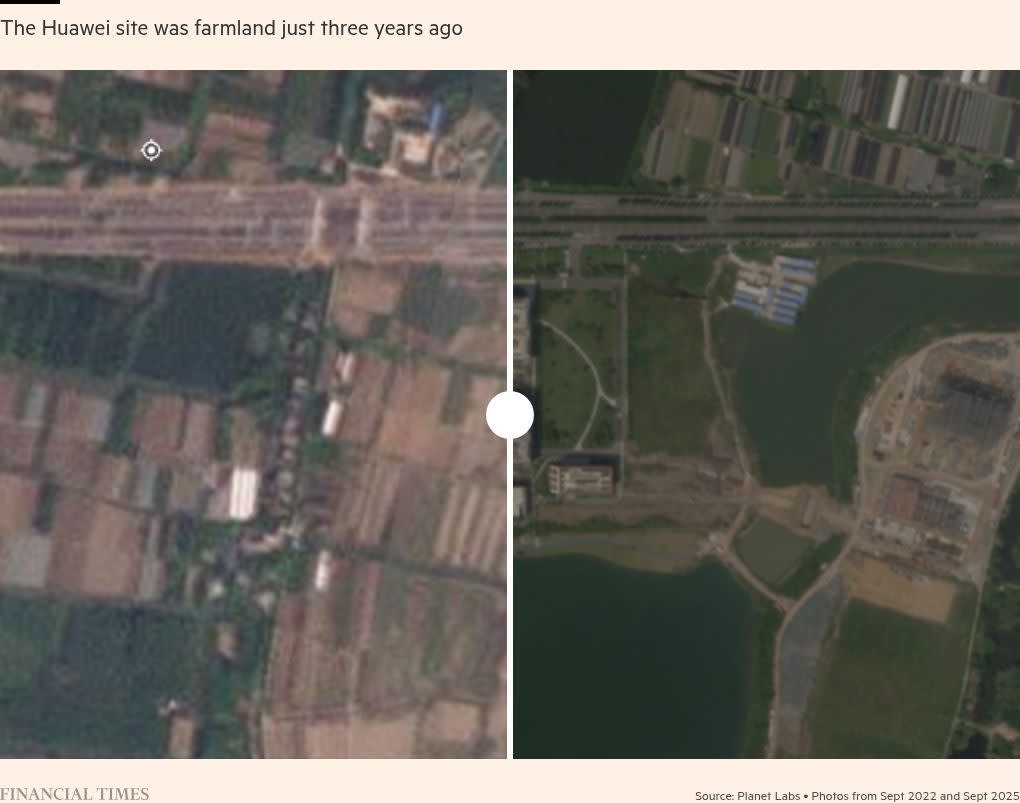

On a 760-acre island on the Yangtze River, rice fields are being turned into a series of huge server farms as part of China’s effort to consolidate its position as an artificial intelligence superpower.

The building work in the farming city of Wuhu is an effort to “build the Stargate of China”, said an executive at a supplier for one of the projects, referring to the $500bn plan by OpenAI, Oracle and SoftBank to build the world’s largest AI data centre in Texas.

The Wuhu “mega-cluster” will not match the scale of the US project. It forms only one part of Beijing’s greater oversight of the country’s fragmented data centres to make them better equipped to handle booming AI demand from consumers.

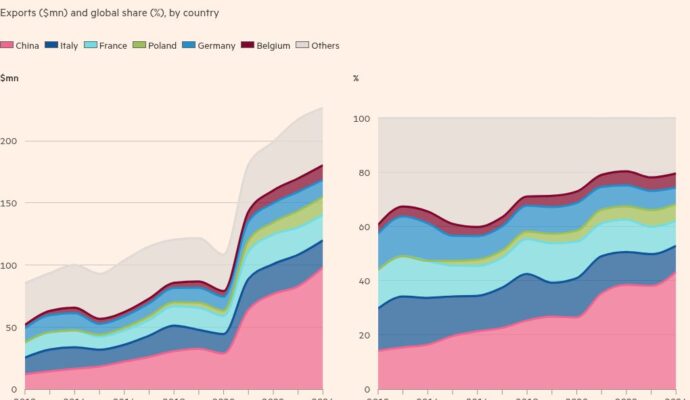

This move comes in response to the strong lead held by the US over access to AI computing capacity, with research group Epoch AI estimating America has around three-quarters of the global computing power, compared to 15 per cent in China.

In March, Beijing unveiled a plan to have existing data centres in remote regions in the west focus on training large language models.

Meanwhile, new server farms are being built in locations closer to key population centres. These will focus on “inference” — the process through which AI tools such as chatbots generate responses, with closer physical proximity to users designed to allow for faster AI applications.

“China is starting to triage scarce compute for maximum economic output,” Ryan Fedasiuk, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and former state department adviser on China. “Beijing is now planning data centre infrastructure with this in mind.”

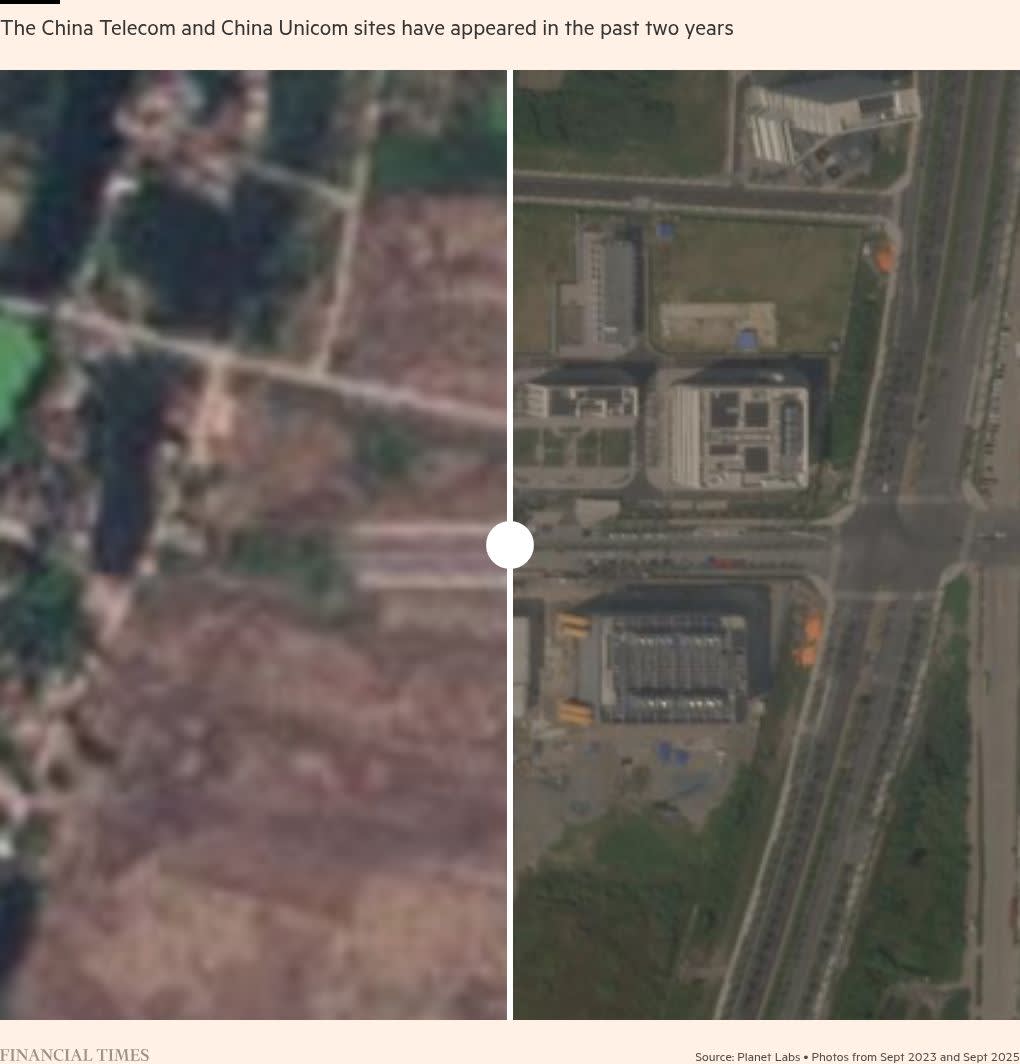

One example is Wuhu’s so-called “Data Island” — home to four new AI data centres, operated by Huawei, China Telecom, China Unicom and China Mobile.

Wuhu’s data centres will cater to the wealthy Yangtze River Delta cities of Shanghai, Hangzhou, Nanjing and Suzhou, while in the north, Ulanqab in Inner Mongolia will feed Beijing and Tianjin.

In the south, Guizhou will supply Guangzhou, and the central city of Qingyang in Gansu will serve Chengdu and Chongqing.

So far, 15 companies have built data centres across the city, according to a local government notice, totalling an investment of Rmb270bn ($37bn).

An executive at a state-owned cloud operator with a Wuhu project said the local government is offering subsidies that cover up to 30 per cent of AI chip procurement costs — more generous than in other regions.

The greater co-ordination is designed to help offset China’s disadvantages to its geopolitical rival. US export controls have also prevented Chinese groups from accessing the best processors and hardware built by Nvidia, the leading AI chipmaker.

Domestic chipmakers such as Huawei and Cambricon have struggled to fill the void in part due to limited manufacturing capacity in China. The US has also prohibited TSMC and Samsung from making advanced AI chips for Chinese clients.

By contrast, American groups such as Meta, Google, and X.ai are racing ahead to deploy tens of thousands of Nvidia’s latest chips. The US Stargate project alone is planning complexes that can house as many as 400,000 processors.

Chinese AI data centres have had to depend on less powerful processors or cobble together advanced hardware from the black market.

However, a network of intermediaries has sprung up across China to secure Nvidia GPUs that are banned for export to China, said multiple people familiar with the dealmaking structure.

One such supplier is the Wuhu-based Gate of the Era, which the FT previously reported has secured large quantities of Nvidia data centre servers that deploy its advanced Blackwell chips which are banned for export to China. The company declined to comment.

Nvidia said: “Trying to cobble together data centres from smuggled products is a non-starter, both technically and economically. Data centres are massive and complex systems, making smuggling extremely difficult and risky, and we do not provide any support or repairs for restricted products.”

China is also seeking to make better use of existing AI processors lying unused in faraway facilities in remote regions.

A boom in construction from 2022 onwards concentrated these facilities in energy-rich but distant provinces such as Gansu and Inner Mongolia.

But a lack of technical expertise and customer demand meant they were underutilised with valuable processors left idle even as demand soared elsewhere.

In many cases, procurement of these AI chips has been financed by local governments, which are unwilling to part with the assets, as they want to boost local GDP.

Instead of physically moving the servers, Edison Lee, an analyst at Jefferies, said, “A technical solution has to be found. That is connecting data centres.”

Beijing has directed the use of networking technology from China Telecom and Huawei to link disparate processors scattered across multiple sites into a centralised computing cluster.

The technology is already used by cloud service providers to connect multiple sites together to create redundancy in case one goes offline.

Chinese telecoms giants, including China Telecom and Huawei, are using the same combination of transponders, switches, routers and software solutions to move computing power from data centres in the west to the east.

However, there are issues with this approach. “Using multiple smaller and older data centres is less efficient than using one bigger and modern one,” said Edward Galvin, founder of data centre research consultancy DC Byte. “It’s about economies of scale.”

Huawei is working on a solution to solve this efficiency problem. The tech conglomerate is leveraging its dual expertise in telecoms and AI hardware to pioneer a new networking technology called UB-Mesh, which claims to double the training efficiency of LLMs across multiple computing clusters by better allocating tasks across the network.

Lee said the move to network the chips together is “an important method of consolidation in this fragmented market”.

Additional reporting by Zijing Wu in Hong Kong