Placing her teacup on the lacquered table, a chic Tokyo-ite turns towards the café’s open window to absorb the beauty of a July day in the Japanese capital. Outside, the leaves on the avenue of ginkgo trees are a rich summer green; the early afternoon sun thrums down on Ueno Park. Crowds wander towards the country’s oldest national museum.

“I so, so love this city. But, over the past few months, I have started to change the route I take when walking through my neighbourhood,” she confesses. “I use smaller streets — the ones the Chinese don’t use. There are too many Chinese around these days. I keep hearing Chinese being spoken everywhere . . . That wasn’t why I left.”

The problem was less acute 18 months ago, when the former business executive, who asks to be referred to as Cao, brought her children from China to start a new life in Tokyo. She had planned her move before China’s middle classes had begun looking at Japan with migratory eyes, before dozens of real-estate influencers on RedNote and other social media had begun fizzing about the opportunities of property ownership in Bunkyo, the Tokyo district where she now lives.

Cao reckons that, in early 2024, there were just three Chinese families, including her own, in her apartment building. Now there are 11, and her observations of furniture deliveries and the language spoken in the lifts suggest more are on the way. A new Chinese community is forming, she says, with the same jealousies and obsessions she left home to avoid. Cao is now plotting a second move to a part of the city with fewer Chinese.

Despite her misgivings about it, Cao is unavoidably a member of this burgeoning diaspora. She is Run-ri: the label given to the wave of middle-class Chinese who have moved to Japan for a lifestyle they see as impossible back home. Some Run-ri want permanent residency in Japan, and the ability to travel back to China for business. Many arrive with no intention of ever returning. Cao says she is here to assimilate, but cannot guess how many of the other Run-ri are.

It’s a phenomenon few saw coming, either in Japan or China. Back in Shanghai and other big Chinese cities, according to more than 20 Chinese residents of Tokyo interviewed by the Financial Times, dinner party conversations are dominated by the mechanics of how to get to Tokyo or Osaka — and stay there.

There is a code at these dinners, which signals a desire to turn the conversation to the topic, according to another Run-ri, Zhang Jieping, a Tokyo-based journalist and entrepreneur who has founded a Chinese bookstore in the city. The way to do it is to ask one’s fellow diners: “How long do you plan to stay?”

“That signals that you want to talk about visas,” Zhang says. “The conversation is always about emigration. Of every three-hour dinner, two will be spent talking about other countries’ visa requirements, how to get out, how to marry a local, how to get an apartment, how to get your parents over there and how to get cash out. Every dinner, every lunch,” she says. “And everyone talks about Japan.”

In these conversations, there is a tacit admission that, for all its “lost” economic decades and flagging dynamism, Japan has got a great deal right. It ranks highly on global indices of peace, economic freedom and property rights. In politics, the nation has kept its poise as others have thrown tantrums, remained supple as others stiffened. It has reliable medical provision, free speech, safe streets, incredible service and astonishingly good food.

Beyond these practicalities, there is an almost ideological element to the movement, says Zhang. “The Chinese mindset for the past 30 years has been that leaving is always better. You leave the country for the town. You leave the town for the city. You leave the city for a big city. You leave the big city for the US. Now, you leave for Tokyo.”

By making their move at this particular moment in history, the Run-ri are shaping the coming decades of Japan’s demographic, social and perhaps even political destiny. Some economists speculate that we are watching the early phases of the country’s ascent to an “immigration superpower”. They are hopeful for an injection of entrepreneurial energy that will prove invaluable in ageing, shrinking Japan.

Others sense trouble ahead, as Chinese buyers propel Tokyo property prices beyond the reach of many Japanese. The government has been pushed to tighten the requirements for the “business manager” visas on which so many Chinese secure their residencies. Some predict a full nationalist backlash, pointing to the klaxons of xenophobia audible in July’s upper-house election campaigns. Because Tokyo is not just a magnet for people wishing to leave China, but for Chinese money too. As well as those seeking a new life, there are some who simply see the city as a financial investment and plan to keep a foot in China for as long as possible.

For now, though, the Run-ri have endowed Tokyo with a status it never expected and is largely at a loss to quantify. Whether it is the intellectuals sniping at Beijing from the safety of Jimbocho coffee shops, the more cash-constrained middle classes finding apartments in areas near good local schools, the richer arrivals steadily occupying more of Tokyo’s prime waterfront, or the very wealthiest establishing roots in the swish “3A” districts of Azabu, Aoyama and Akasaka, the Japanese capital is being recast as a Chinese haven.

The word Run-ri — broadly used to cover the middle-class entrepreneurs, white-collar workers, wealthier academics, retirees and intellectuals moving to Japan for aspirational reasons — combines two Chinese characters. The run primarily means liquidity or prosperity, but its similarity in sound to the English word “run” also conveys the idea of flight. The second character, ri, is the first in the Chinese word for Japan. The term has been around for a few years. But it has jostled into the mainstream lexicon since about 2022, the peak of the Shanghai Covid-19 lockdowns and, for many cosmopolitan Chinese, a psychological tipping-point: the “life inflection point”, as many describe it.

The numbers are startling. Without ever having declared any kind of open-door policy on immigration, Japan has quietly addressed both its demographic decline and worker shortage by allowing its non-Japanese population to surge to about 3.5 million, or just under 3 per cent of the population. The number of foreign residents rose by an average of roughly 1,000 per day over the course of 2024, of which about 10 per cent were Chinese. By next year, according to some projections, the total Chinese population of Japan is likely to hit a million.

The Run-ri tend to have certain things in common: relative wealth, an obsession with education, a faith in Tokyo real estate as a store of value — and aspirations to own a seven-seater Toyota Alphard.

“Yes, I am Run-ri. I think I fit many of the descriptions,” agreed a 41-year-old IT engineer who left Shenzhen in 2022 and was dropping his son off at an after-hours tutorial school near Toyosu station when approached by the FT. The school is one of many in pockets of Tokyo where Chinese represent more than 10 per cent of the student cohort. There has also been a surge of Chinese enquiries for places in Tokyo’s international schools, to as much as 60 per cent of the total in some cases.

The engineer’s apartment is nearby in the Branz tower, a huge block of high-end flats overlooking Tokyo Bay, of which about 20 per cent are believed to have been sold to people with Chinese names, according to local estate agents. A listing for a three-bedroom flat in a nearby tower displayed in the window of a Chinese-owned estate agent in Roppongi, has an asking price of ¥350mn ($2.4mn). Other newly built developments nearby, including a vast complex built as the athletes’ village for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, have similar ratios of Chinese buyers.

“My wife and I wanted a city life, and we thought we had that in Shenzhen. But during the pandemic, and maybe before that, we saw a more scary side of China,” the engineer said. “A state that knew it could do anything it wanted, and no longer seemed interested in protecting the middle class. It was difficult to leave our home, but also easy to start a new one here.”

For many Chinese, the first proper encounter with Japan and Japanese people is as tourists. Some seven million visited Japan from mainland China last year. Often, these visits dispel negative images of Japan that have been established over decades.

Cao first came to Tokyo in 2017 on a business trip for the trading company she was working for, and she quickly fell for the city. “I had decided by the following year that I wanted to move here. I liked the calmer atmosphere. Even when places are crowded, they feel calm here.”

Cao homed in on Bunkyo ward for its reputation as the educational heart of the Japanese capital. She is a single mother of two and has stretched herself financially to make a life for her family in Tokyo, and the state-run schools and private crammers in the area have a reputation for quality. There are some local government subsidies for residents on tight budgets. Children who arrive in the local public schools in Bunkyo not speaking Japanese as their first language are offered a certain number of extra Japanese language lessons.

Meanwhile Japan’s schools are emptying. In 2016, the number of Japanese babies born fell below one million for the first time since records began in 1899. By 2024, the number was just 686,000. In rural Japan, that has meant a steady beat of school closures, but in the middle of Tokyo, it means there are places available. The effect has been striking.

Very quickly, Cao found herself pulled into an educational arms race with other Chinese parents. “The middle class? They are super, super competitive, and that is a big part of what they want here,” says Cao, opening her phone to reveal a school chat group of Chinese parents. It is a cavalcade of paranoia and passive aggression. “Should the kids go to a private or a public school? Should they do this particular exam? Is that school good? Is that teacher intelligent enough? What scores did everyone get? It’s not what I wanted,” she says.

As the Chinese community in Bunkyo has expanded, the children have begun to group together and do not speak Japanese outside school, she says. Within school, it is already becoming a distraction. “A lot of Chinese like to be in that environment, but I do not,” says Cao, who prefers not to be too explicit about where she plans to move next for fear that other Run-ri will follow.

Many thousands of Chinese leave their country every year — for the US, Canada, Australia, Europe or other parts of Asia. Historically, China has produced a large flow of emigrants with almost no assets. But, more recently, it has become a world leader in the export of high-net worth individuals (those with liquid assets over $1mn), with an estimated 12,500 departing in 2024.

Economic instability and tightening authoritarianism at home is now producing a third category of leavers: middle-class Chinese headed for what might be described as the Bolt-hole of the Rising Sun, just a three-hour flight from Shanghai.

At the same time, President Donald Trump and his Maga movement have caused many would-be Chinese emigrants to cross the US off their preferred-destination lists. And a small but growing number of Chinese, known as the Er-run (“second runners”), who moved to the US years or even decades ago are jumping ship again, to Japan.

Despite Tokyo’s vulnerability to regional tensions, trade wars and natural disasters, the city seems to suit an era of globalised uncertainty. A chronically weak yen makes everything seem cheap to those with foreign assets. And, for now at least, Japan makes it relatively easy for incomers to obtain a visa as a highly skilled professional or business owner. Setting up a company of a type that supports at least one business manager visa requires roughly $35,000 of capital and a further $5,000-$10,000 of administrative fees, according to several lawyers who described the process. Plans have been mooted by the government to significantly expand the minimum required capital

Was it any coincidence the Alibaba founder, Jack Ma, chose to move to Tokyo, of all possible cities, when he fell out of favour with Beijing in late 2021? “Of course it was not,” says one close Japanese acquaintance of the billionaire, who used to meet Ma regularly at a Chinese-owned private members’ club in the city. “What is far more fascinating is that the same calculations now make perfect sense to those with only a minuscule fraction of Ma’s fortune.”

Ma was followed to Tokyo by others from China’s business elite, a trend that only added to its aspirational allure. Occasional sightings of Chinese tech founders walking nonchalantly around Nogizaka or Ginza districts in casual clothes has become fodder for Chinese social media as well as right-of-centre Japanese media outlets harrumphing that no good will come of this migratory tsunami.

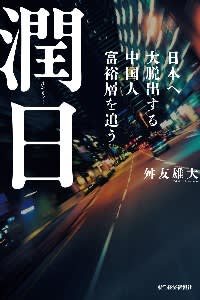

But it is the more modest incoming Chinese wealth that demands the most scrutiny, says Takehiro Masutomo, an academic and journalist whose book, Run Ri, was published in January. The book (available in Japanese only) is the first serious probe of the Run-ri phenomenon as a socio-economic force, and continues to sell strongly in Japanese bookstores. Even without Masutomo’s revelatory work, which notes the ski-resorts, forests, sake breweries, hotels, restaurants and other businesses being cornered by incoming Chinese buyers, it is becoming impossible to ignore what is happening. As Masutomo points out, the total size of the Chinese population residing in Japan was about 200,000 in 1995. It rose through the early 2000s, and settled at roughly 700,000 between 2010 and 2021. Since then, though, the numbers have soared.

The focus of Masutomo’s book, and his estimate for the size of the population he categorises as Run-ri, is about 100,000 of these immigrants. Masutomo notes distinct waves of Chinese immigration. Between the early 1980s and the early 2010s, settlers were often from Fujian and China’s north-east, and would live mostly in rural parts of Japan or the cheaper suburbs of Tokyo and Osaka. They were in the main trainees or students, had few assets, could speak Japanese and were pro-Beijing. A much larger proportion of today’s arrivals, meanwhile, come from Tier-1 Chinese cities, live in the central wards of big metropolises, have comfortably sized financial assets, are not particularly fluent in Japanese and have little affection for the Xi Jinping regime.

A Shanghai native who used to work in online media and who asked to be known as James, is one of those preparing to leave the city that made him relatively well-off. James’s wife will move to Japan on a highly skilled professional visa, and he will follow. They are just weeks away from becoming Run-ri.

After extensive research, James fixed on Urawa, a suburb in the prefecture abutting Tokyo, about 70 minutes from the heart of the city, as the place to live. The property is relatively cheap and the public education is pretty good, he says. But suffusing all these decisions is something else: “In the past, it was always about America. Nobody wants to go to the US now. Not with Trump. A lot of us have membership of the Chinese Communist party, just because that was what we needed to do to get ahead in business. So now, with that membership, you are afraid you’ll probably be denied a [US] visa.”

Tokyo feels politically safer. “I don’t know who will win between the US and China, but Japan is in the middle. Japan is a good place to set up my second life,” says James. “Japan is stable. It has rational politics. It has no Chinese nationalists. No Maga. It just has a normal society. And I think that the number of people [in Shanghai] who share this kind of thinking is on the rise. Everyone has a third term for Trump or a fourth term for Xi in their mind, and they don’t like it.”

Once the Run-ri have decided to leave China, they confront a series of further practical obstacles and financial risks. A parallel service industry of Chinese and Japanese entrepreneurs has emerged to solve these problems.

At least one private hospital in central Tokyo has renovated entire floors to cater to wealthy foreigners, with an assumption that the majority of these will be Chinese. Japan’s biggest investment banks have expanded their domestic services to target the wealthiest Run-ri. Some of Japan’s best sushi and teppanyaki chefs, said two Japanese restaurateurs who have competed to hire them for their own establishments, have vanished behind the doors of private members’ clubs built principally for Chinese clients. Ambition DX, a Tokyo-listed real-estate brokerage, explicitly advertises itself as an expert in catering to the Run-ri boom.

Alex Hayashi, the founder of Compass Capital, which was started in Tokyo in 2019 and offers consulting services to Chinese investors from an office on the edge of the Imperial Palace, suggests that few in Japan, whether in the financial services sector or the government, have understood how unlike any previous wave of immigration the current influx of Chinese is.

“Why are there so many Chinese entrepreneurs here? Because they feel they have no other options,” he said. “In the past, people trying to get out of China would head for Singapore, but it’s too small, there are not enough investment opportunities. There was a previous wave of Hongkongers wanting to move to Tokyo, but they weren’t looking for double-digit investment returns like the new generation of Chinese do.”

The most tangible impact has been on property prices in Tokyo — one issue over which populist Japanese politicians have been able to stoke public anger. The prices of higher-end apartments in the capital, and the land in central wards on which low-rise houses can be built, has risen significantly since 2022. Masutomo says the influx is incredibly jarring for local Japanese. For more than 60 years since it became a developed nation, Japan was able to think of itself as the richest and most sophisticated nation in Asia. That idea has now been challenged by wealthy colonists, and is particularly humiliating because of the weakness of the yen.

“I think this is the first time that Japan has really confronted richer and more sophisticated immigrants from Asia,” says Masutomo. “It is making Japanese people feel poor in their own country.”

A sporty man in his thirties, who asks to be known as Guo, meets me in a busy café in a backstreet of Nakano — a lively, shabby warren of often Chinese-owned restaurants and bars. Guo decided to move with his wife from Beijing to Tokyo in 2022. They were able to get working visas in about four months, he says. Many of their friends are also in Tokyo on business manager visas. To qualify for these they have either set up companies, or bought small, failing Japanese businesses on the cheap.

Guo works for one of what he reckons are about 50 Chinese-staffed real-estate agents in the rental or sales business, catering to other Chinese. Many of his current colleagues left or were cut from big Chinese tech companies such as Tencent, Baidu, Alibaba and Meituan. Some went to work for Japanese tech giants like Rakuten. Many ended up in travel companies.

“We get 200 enquiries every month, and perhaps a deal or two every week. There is an urgency in their buying, because they have seen property prices collapse in China and they see Tokyo as a place where property values will hold,” Guo says.

About half of the deals are made by Chinese who intend to live in the properties. They have specific requirements: enough floorspace to bring elderly relatives over from China to live with them in the future or entertain visitors from the homeland on shopping and sightseeing trips.

And, “very important, they want properties with a parking space big enough for an Alphard,” Guo says, referring to the imposing Toyota people carriers that have become the favourite Run-ri vehicles. A new Alphard would cost the equivalent of $130,000 in China and commands extraordinary status. In Japan, the same car costs the equivalent of $40,000. “They have seen celebrities in China being driven around in them. They want to buy all of that prestige but for a really low price in yen.”

When Guo and his wife arrived in Tokyo they faced the standard set of problems. Very rich Chinese are able to set up bank accounts or paper companies in Singapore and Hong Kong, making it easier to remit funds into Japan, or to open Japanese bank accounts. But for most Run-ri, says Guo, opening a Japanese bank account, getting savings out of China or even renting a flat is a challenge.

An extensive underground banking system has emerged to circumvent China’s restrictions on capital flows. Guo and three other people interviewed by the FT estimate that about 70 per cent of the Tokyo-based property transactions by Chinese buyers involve one of these underground banks.

It works like this. The banks convert renminbi into yen via a complex network of laundering facilities that include dollar-generating Chinese import businesses in Africa. The customer then arranges for funds to be delivered to a representative of the bank at premises in China, and sets up an appointment to receive the yen at various locations in Japanese cities. Cash is couriered in huge quantities — one agent said that a North Face waterproof rucksack is currently the favoured receptacle — with the underground bankers taking as much as a 100 basis point margin on each transaction.

A lot of time, says Guo, is spent counting out cash on tables in anonymous upstairs offices. The transfer of a million dollars’ worth of renminbi into yen, say those who have used the services, takes about a day. “It has to be very discreet. A lot of the customers are the families of Chinese government officials,” says Guo.

The “accidental” founder of several Chinese bookstores, Zhang Jieping was born in the Chinese city of Wuxi and moved to Tokyo in 2024. Her hometown, a city of almost 7.5 million people on Lake Tai, is increasingly indistinguishable from the urban immensity of Shanghai.

Zhang leads the way from a café near Koenji station through streets of grey and brown apartment buildings and offices punctuated by older buildings: a pet shop, an Italian restaurant and several hairdressers. Turning into a residential block, we stop at the door of a ground-floor apartment. A sign reads “Feidi Zhi Ye” in Chinese characters and “Nowhere Party” in Roman letters. Inside, the rooms have been converted into a small, elegantly congested bookshop selling the sort of commentary, analysis and criticism that cannot appear on the shelves in Xi’s China.

Zhang’s shop, which opened this year, is a narrow safe space within the wider haven of the city. It preserves an open area between the stacks for the kinds of lectures, seminars, book clubs and discussion groups that are kept so deliberately vestigial in China. These events, she says, are merely the physical expression of a much larger community that meets online for the sort of grand dialogue that Tokyo seems to encourage.

The Nowhere is the fourth Chinese bookstore to have opened in Tokyo in the past three years. Daxiangjie (One Way Street) and Juwairen (The Stranger) in other parts of Tokyo, are probably the best known. Zhang, who worked as a journalist for more than a decade, left mainland China and was living in Taiwan for the first year of the pandemic. She had been in Hong Kong before that, but was reluctant to step back behind the curtain of China’s new national security law, so decided to open a bookshop in Taipei.

The shop specialised in selling Hong Kong books to migrants who had moved to Taiwan. “It was for them at first, but then I realised it could be somewhere for all intellectual exiles,” says Zhang. She subsequently opened branches in Thailand’s Chiang Mai and The Hague, and is planning another in New Zealand. “A bookshop owner follows people’s demands. So one role is as a business owner, the other is as an observer of communities. It’s like a window.”

The window her Tokyo shop opened has been revealing. About 60 per cent of customers are from mainland China. Some of the books she sells are forcefully banned there, others are simply not sold. While there is interest in what she calls the “really juicy topics” — direct criticism of the Xi regime and senior party officials of a sort that sell brilliantly at the branch in Thailand — the Run-ri in Tokyo are losing interest in that subject, she says, to read around more general geopolitical topics.

Critically, she says, there has been a shift in mindset. Masutomo agrees. By mid-2024, when he had probed more deeply into the Run-ri phenomenon, he discovered something unexpected. The Chinese who attracted the attention, and opprobrium, of the Japanese media tended to be the young and the rich. But there was also a cohort of older Chinese who were moving to the suburbs of Tokyo. Among these was a growing number of Chinese intellectuals who would appear at academic events in the city.

“I realised I was looking at an intellectual flight to Tokyo. Something completely new. I don’t think they are trying to start a revolution from here, but it is interesting. The steady opening of bookshops and the concentration of Chinese intellectuals is quite unique. I don’t know other major cities where that happens apart from Tokyo.”

Masutomo argues that the simultaneous integration of Chinese wealth and Chinese intellectuals to Tokyo will be key over the coming decade. “If they combine in a meaningful way, that will become political and they might be monitored more seriously by the CCP,” he says.

One such dissident in his forties, Jia Jia feels relatively free in Tokyo. His haven, through a visiting scholarship, is the University of Tokyo. His main outlet is YouTube debates with other Chinese intellectuals in Japan, which can become both feisty and critical of Beijing. Before fleeing to Japan with his wife, Jia was detained by the Chinese authorities under suspicion of involvement in an open letter calling on Xi to resign. He was released, but still felt the scrutiny of the authorities.

“I don’t think I’m like most of the other Chinese who have come to Tokyo,” Jia says. “I was chased by the police. I am like a dissident. What has made me most happy has been coming to Tokyo. Here I sleep comfortably at night. I live without fear.” But Jia is conscious that Tokyo is changing him. He has faced criticism for not staying in China to continue the fight. The haven is softening his edges and even, he ventures, turning him a little more Japanese.

These days, he has begun to feel there is more to life than fighting the Communist party. His writing has slowed, and he has come to appreciate the peace in Tokyo. “Some Chinese seek to find China in Japan,” says Jia, “others try to change the course of China from Japan. A third group just tries to forget about China as soon as they arrive in Tokyo.”

While that assessment may perfectly capture how many Run-ri see Tokyo, there is, as yet, no such neat summary of how Tokyo views this rapidly expanding segment of its population. The newcomers are a reminder that the city’s greatest asset is its capacity for reinvention, reconstruction and reimagining. Those powers have already been tested by war, natural disasters and economic catastrophe. The odds that it can manage immigration are good.

Leo Lewis is the FT’s Tokyo bureau chief