Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

China has ordered the solar sector to rein in overcapacity and cut-throat pricing as the biggest manufacturers suffer billions of dollars in losses.

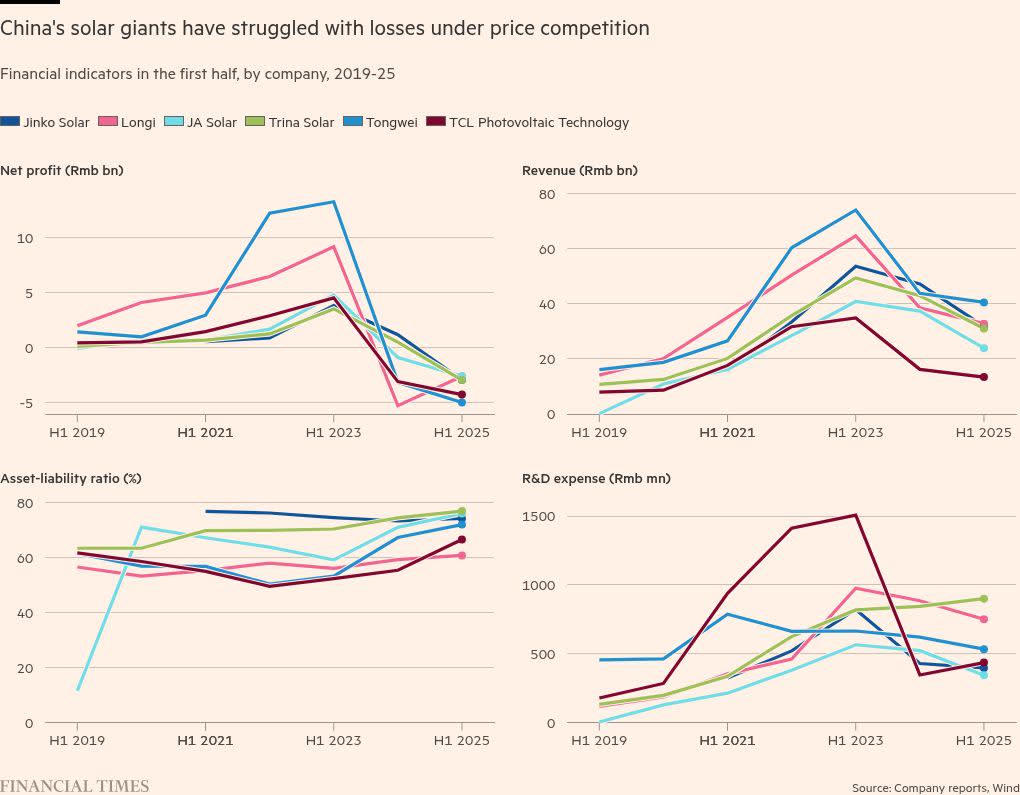

Six of the largest Chinese cell and panel makers saw their combined first-half losses double to Rmb20.2bn ($2.8bn) from a year earlier, with all but one reporting widening losses, according to financial information provider Wind. The losses compare with record profits in 2022 and 2023.

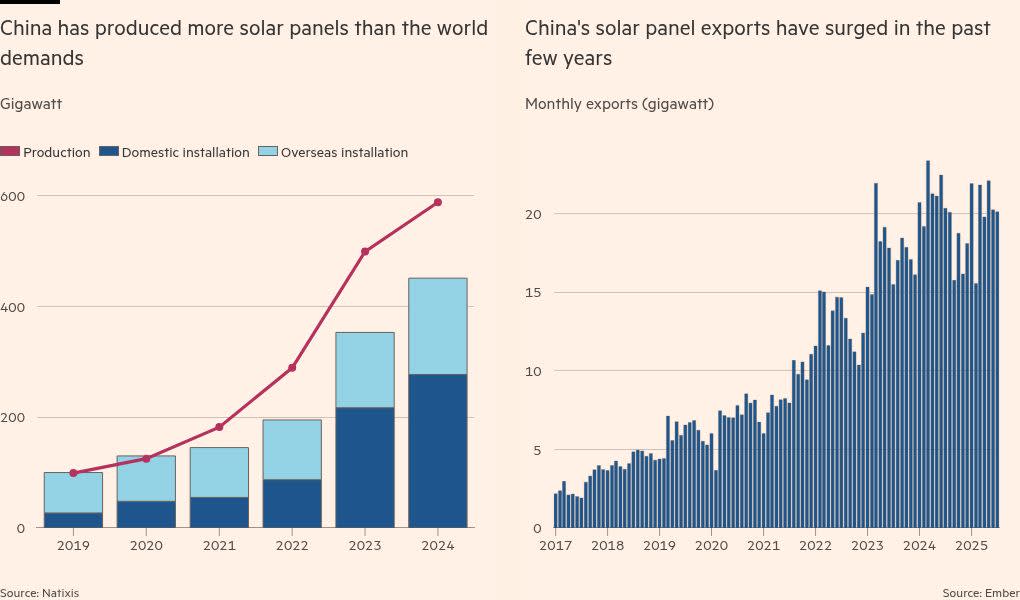

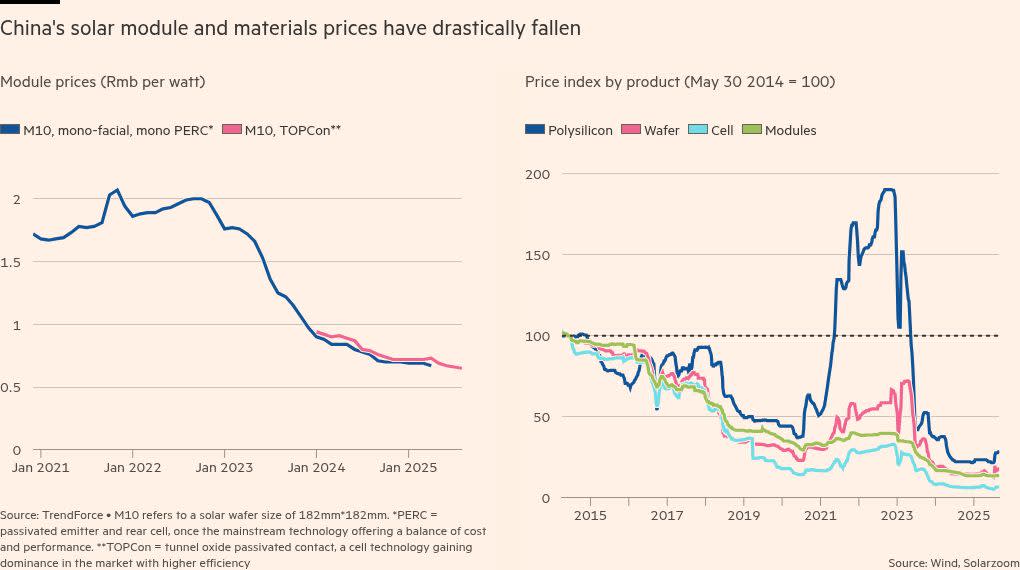

Solar is one of the industries at the heart of Beijing’s concerns about “involution”, which refers to excess production fuelling a race to the bottom in prices. It has added to China’s deflationary pressures, a key economic problem for President Xi Jinping, and stoked tensions with trading partners as companies turn to exporting their products.

“This ‘animal spirit’ made solar companies succeed in the past, and now it is the same ‘animal spirit’ — ultra competitiveness, wanting to outlast their competitors — that has led to this mismatch” between supply and demand, said Bo Zhengyuan, a partner at Beijing-based research consultancy Plenum.

In early July, executives from 14 of China’s biggest solar companies were summoned to Beijing, where newly appointed industry minister Li Lecheng said companies must “resolutely crack down” on disorderly competition and speed up the closure of underutilised factories.

But Li also noted that the sector had transformed “from weak to strong” and now boasted a “leading edge” in scale and technology, highlighting the tension between reining in the industry and encouraging innovation.

China controls about 90 per cent of the world’s solar cell manufacturing capacity and boasts the industry’s most advanced technology. The country has ambitions to replace fossil fuel imports with domestic renewable energy, but a rapid decline in earnings has highlighted failings by executives and regulators to control excessive price wars.

Factories in China produced 588 gigawatts of solar cells last year, surpassing domestic demand of 277GW and overseas demand of 174GW, according to Natixis data. The utilisation rate of Chinese solar module factories was 54 per cent, according to Goldman Sachs data.

Expectations for slower growth in some international markets have been exacerbated by weakening domestic uptake as China transitions to market-based pricing for electricity. Solar makers’ combined revenues fell more than 23 per cent year on year in the first half to Rmb173.5bn.

“The situation has worsened dramatically . . . I couldn’t believe it, how fast it has deteriorated,” said Alicia García-Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist at Natixis. “I really don’t know how these companies are going to survive.”

Policymakers and regulators are divided over how much photovoltaic capacity can be retired immediately, according to analysts and officials. Another point of contention is whether to provide state funding to a proposed industry-led vehicle that can buy and shut down excess capacity, which could put the government in the uncomfortable position of picking winners and losers.

Beijing is also pushing solar exports to developing countries as part of Xi’s flagship Belt and Road foreign policy. “This issue involves multiple policy goals and needs to be treated delicately,” said a Beijing official familiar with the discussions.

At a meeting among six government ministries, leading solar companies and industry bodies last month, officials pledged to crack down on products being sold below cost and promised stronger oversight of new project development and the exit of outdated capacity.

Plenum’s Bo said he expected regulators in the short term to increase enforcement of energy efficiency and other environmental standards, a moderate approach to start cutting capacity at older factories.

While it was clear the government was “quite unsatisfied” with how manufacturers had expanded production despite slowing demand forecasts, any structural change would be difficult to achieve given the culture of ruthless competition, he added.

Industry insiders noted that each of China’s biggest solar groups, though privately owned, had a close relationship with the respective provincial government of their headquarters, implying financial and political support through times of crisis. This could complicate central government efforts as provincial officials try to keep factories running to support local jobs and investment.

Chinese companies have sought to align themselves with Beijing’s long-term aim of technological leadership by maintaining relatively strong research and development spending, said Ken Liu, head of China renewables, utilities and energy research at UBS.

Combined research and development spending by Longi, JA Solar, Trina, Tongwei, Jinko and TCL was Rmb3.4bn in the first half of 2025, down about 8 per cent from a year earlier. As of the end of 2024, the groups collectively had nearly 17,000 R&D employees, double five years earlier.

The companies did not respond to requests for comment.

“If you look at the evolution of solar from 2020 to 2025, the technology improvement is actually quite massive, getting closer to 30 per cent conversion efficiency from 20 per cent just five years ago,” said Liu, referring to an industry metric for solar cell performance.

Ultimately, analysts said Beijing might be resigned to accepting a period of financial weakness, given expectations of solar’s central role in the energy transition in China and abroad.

“I think the leadership holds the view that the minute foreign demand recovers, [the Chinese companies] dominate,” said García-Herrero of Natixis. “There’s no sector where they dominate more than in this sector, so they just have to wait.”