During the heyday of Chinese low-cost manufacturing, the town of Houjie was renowned for both its shoemakers and the raucous nightlife laid on for the thousands of foreign and domestic buyers who visited each year.

Like other parts of Guangdong, it boomed after China became the world’s export powerhouse and the southern province became a test bed for capitalism and foreign investment as the home of the country’s first special economic zones.

But now, many of its factories are empty, and their surrounding restaurants and businesses are suffering, locals say, as trade tensions unleashed by US President Donald Trump compound the structural decline of low-end manufacturing and weak consumer sentiment.

The retreat of manufacturing to south-east Asia has left Li Jilei, a chef who moved to the factory town of Houjie more than a decade ago in search of work, isolated and alone. “Business is bad . . . a lot of factories have left,” said Li. “[But] our kids are at school here. We can’t move ourselves.”

China and the US are locked in protracted negotiations over trade. While Washington has slashed additional duties on Chinese goods to 30 per cent while talks continue, no one doubts the impact created by increased levies and heightened uncertainty. With exports totalling almost Rmb5.9tn ($821bn) last year, Guangdong is vulnerable.

“It’s going to be massive,” said Alicia García-Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist at Natixis. “The companies [in Guangdong] are at the core of the trade war.”

While factors such as a property sector slowdown and flagging domestic demand began to bite “well before” this year’s tariffs against Chinese goods, Washington’s latest trade onslaught will hammer the region’s growth prospects, she said.

“It’s not a province that is doing as wonderfully as it used to,” added Garcia-Herrero. “Something is really not working.”

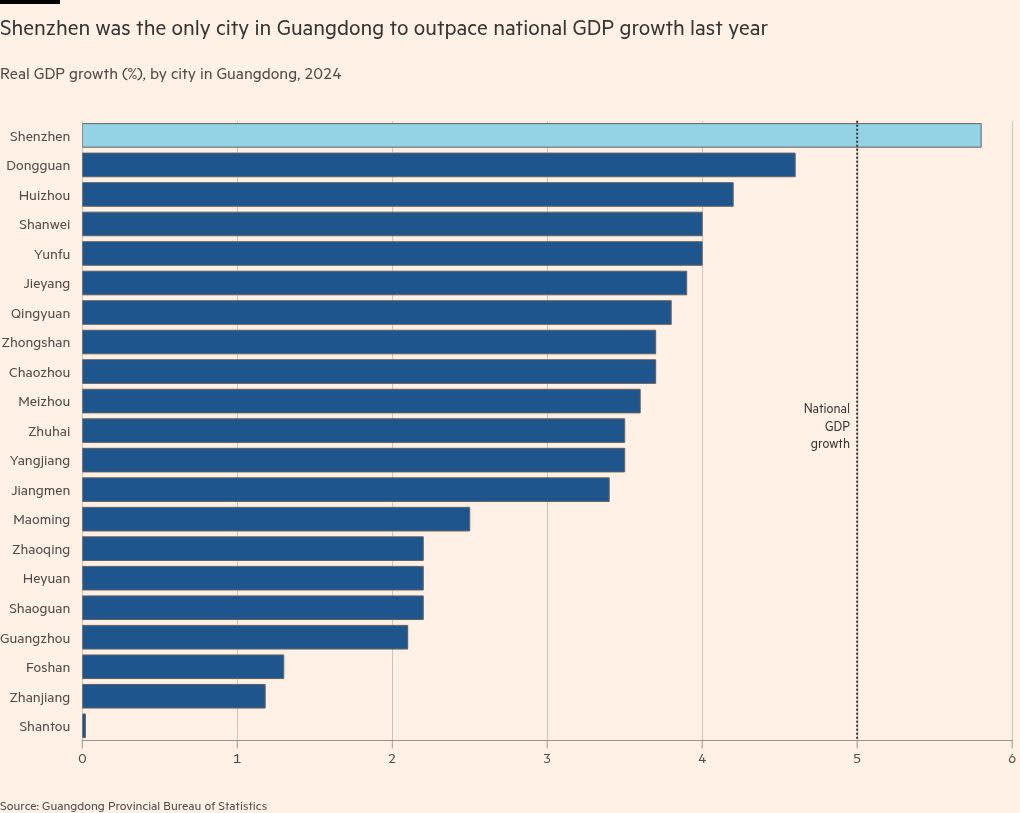

Guangdong grew just 3.5 per cent last year, missing its target for the third consecutive year and coming in well below the national rate of 5 per cent.

Shenzhen, a high-tech hub and one of China’s richest cities, was the only city in the province to achieve growth higher than the national average in 2024.

Annual growth in the provincial capital of Guangzhou was just 2.1 per cent. Neighbouring Foshan, known for its production of furniture and household appliances, grew 1.3 per cent.

The economy of Shantou, a coastal city that was one of China’s original special economic zones, expanded just 0.02 per cent.

The province’s export credentials date back to the 17th century, when it was one of the first places in China to be partially open to foreign traders. In 1957, following the first Canton Fair, it became the conduit through which much of China’s foreign trade was conducted.

GDP per capita in Guangdong increased more than 220-fold in the 40 years from 1978 to 2018. Nowadays, its economy is slightly larger than South Korea’s.

But even before Trump’s re-election, the retreat of low-cost manufacturing to cheaper hubs had dented the province’s growth momentum.

Driven higher by intense speculation during the boom years, property prices in the province have been slower to recover than in other rich regions. It is also home to several of China’s most prominent indebted developers, including Evergrande, Kaisa, Vanke and Country Garden.

Analysts say the slump has also contributed to fragile consumer and business confidence, with metrics such as retail sales significantly underperforming the national averages.

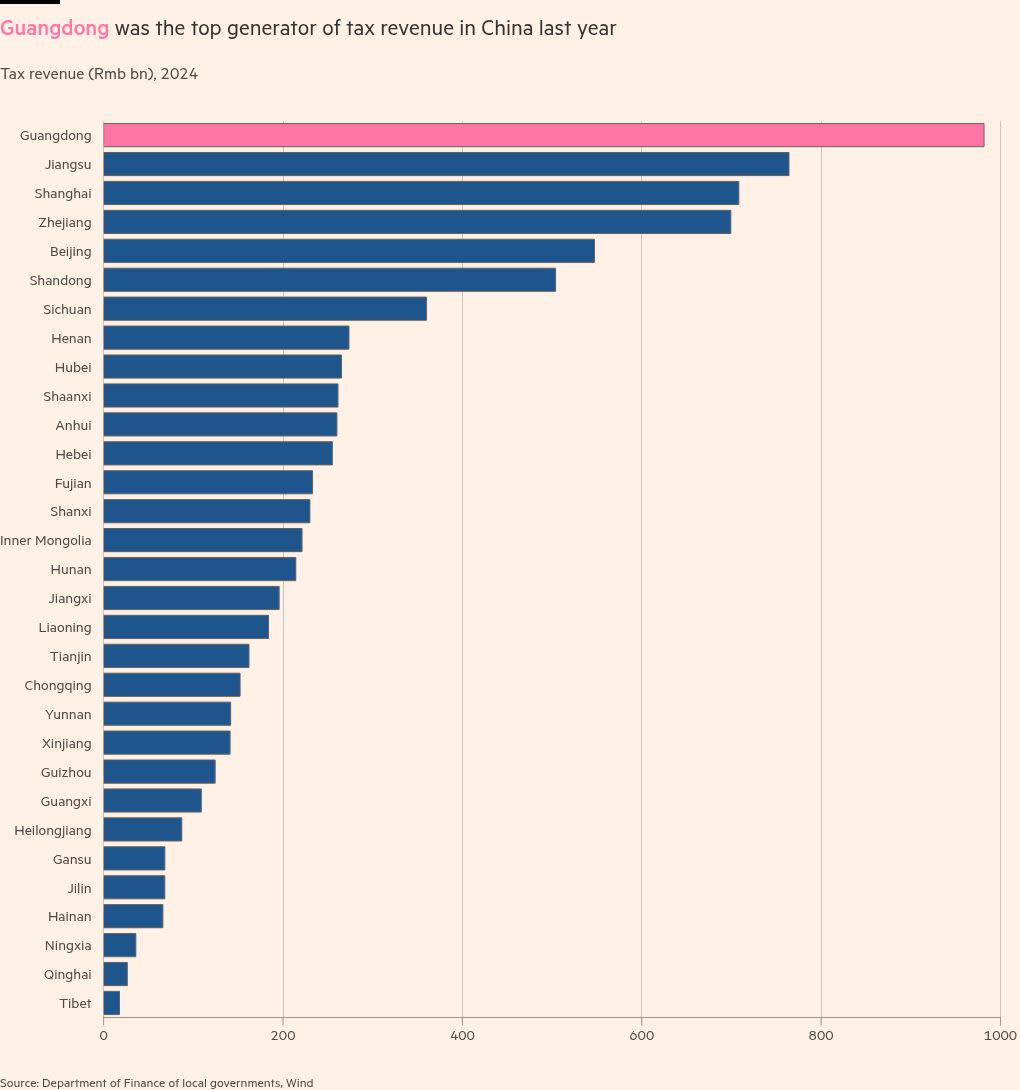

The slowdown in Guangdong also has national implications.

The province contributes more to central government tax revenue than any other. In recent years, a national downturn has meant Beijing has redirected a greater proportion of that tax revenue to stimulating growth in poorer regions.

“The overall economy is not doing very well, [but] you still have to pay your taxes,” said Sam Kwok, an analyst at Fitch Ratings.

While exports had been a crucial lifeline for the Chinese economy in recent years, Natixis’s Garcia-Herrero said that the latest US trade tensions were pushing even high-tech exporters such as Guangdong-based electric vehicle maker BYD to look to expand their production overseas.

Trump’s cancellation of the so-called “de minimis” tax exemptions for small-value shipments would also hammer Guangdong disproportionately, given that many suppliers to Shein and Temu, two of the largest users of the loophole, were based in the province, she added.

Few places encapsulate the stalled promise of Guangdong’s export model better than Ronggui, a manufacturing subdistrict in the Pearl River Delta.

Ronggui was the first such hub to have a total industrial output exceeding Rmb100bn. Deng Xiaoping, who steered the opening of China’s economy to the world as its leader in the 1980s and 1990s, heaped praise on the area.

But growth in Ronggui, which is driven by the production of air conditioners and refrigerators, has since stalled. Margins for such mid-end products have declined, while high-tech industries have taken root elsewhere. Growth in nearby Foshan has also declined precipitously.

“I’m just about able to make my living,” said Zhou Jingjing, a street food hawker selling Rmb6 ($0.83) dumplings outside an industrial park, adding that income from her evening snack stall had suffered as fewer factories in the area were asking their staff to work overtime.

Liang, a 35-year-old metal worker at a Ronggui refrigerator factory, said that his monthly income had declined to about Rmb7,000 from Rmb9,000 in the past two years as Covid-era export demand petered out.

While he was confident that the factory would provide him with a stable income, the value of his property nearby had also moderated amid a nationwide real estate slump.

“I have a mortgage here and my kids are in school,” he said. “I don’t dare go out [and find other work].”