Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Three’s a crowd — at least, it should be when it comes to stock markets in the same country doing the same thing. Fragmentation divides investor attention and liquidity. And when new entrants steal all the limelight, it can lead to a predictable cycle of booms and busts.

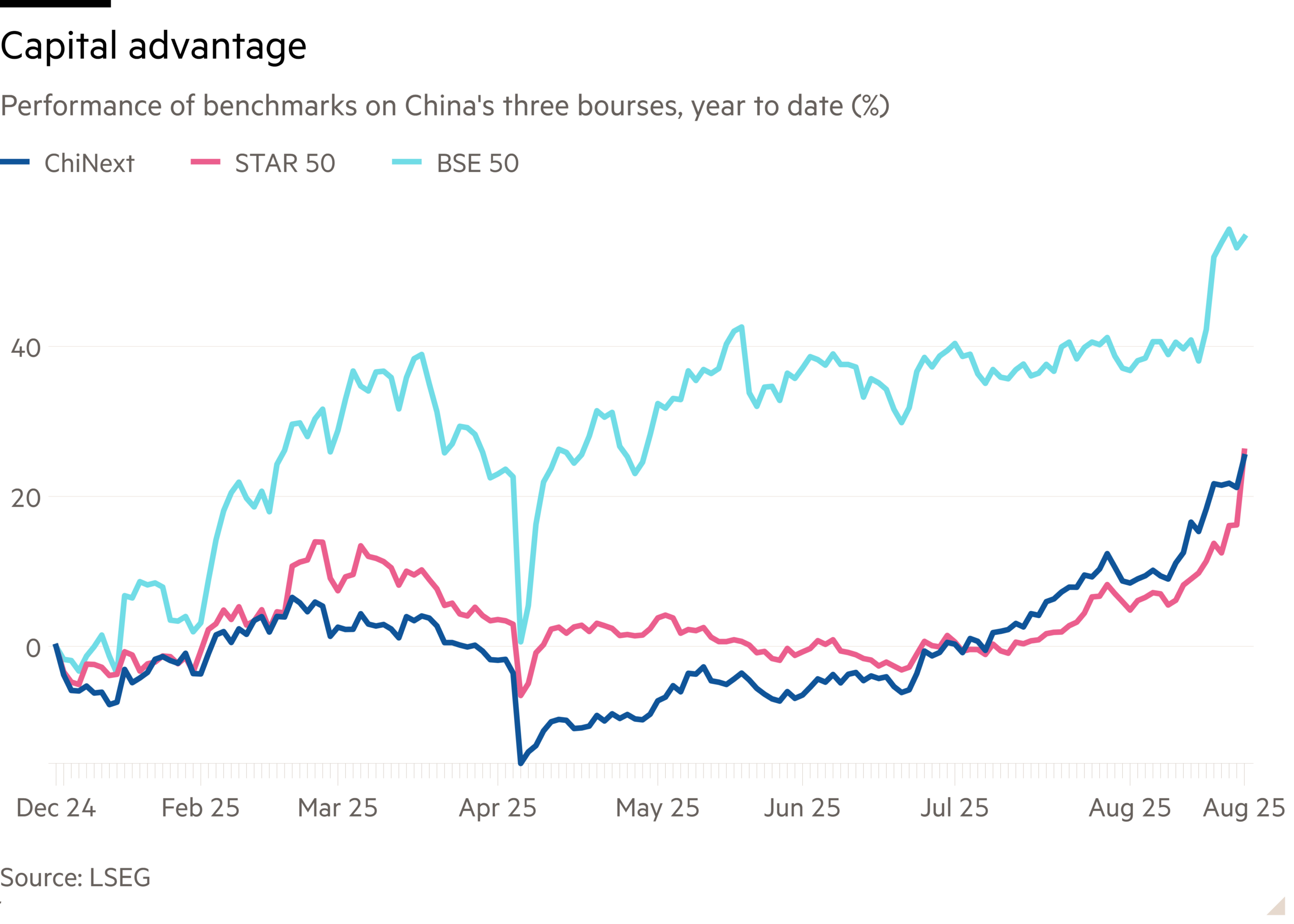

For evidence, take a look at China’s Beijing Stock Exchange, the newest of its innovation-focused bourses. This year it has attracted more than twice as many listing applicants as its two rivals combined, while an index of its top 50 listings is up more than 50 per cent.

Beijing’s bourse was launched in its current form in 2021 to help innovative smaller companies raise capital. It promised fewer requirements, plus a speedy system to process applications. Before that came Shanghai’s STAR Market in 2019, notable for giving companies more control over their listing timetable. A decade earlier, Shenzhen’s ChiNext caused a stir by lowering the profitability requirement for companies seeking to list.

This may sound like steady progress, gradually reducing burdensome listing requirements as officials and investors gain in experience and confidence. But there’s only so much investor attention to go round. Both ChiNext and STAR launched amid speculative frenzies, with listed stocks reaching astronomical valuations and sucking excitable funds away from other markets — until the boom turned to bust.

Beijing has already been through one such soar-and-slump cycle after officials, worried by rocketing prices in late 2023, issued warnings and notices regarding abnormal trading in roughly half the bourse’s 200-odd stocks. That has proved no deterrent to IPO wannabes: 113 plans have been filed with the exchange this year, according to Wind data, compared with 44 combined for STAR and ChiNext.

China’s excitable markets have burned many investors over the years. But the real pain is inflicted on companies that make it on to the latest hot exchange but then find they are all but stranded when attention moves elsewhere. Switching to a better bourse might sound simple but it isn’t, given the need to get official approval.

How much better if the three were one exchange — or at least operated under one set of rules — allowing companies to rally or fade based on their merits, not their stock exchange’s address?

China’s markets, including Hong Kong, are technically the second largest in the world after the US, but they are in practice less than the sum of their $18tn combined market capitalisation. An ever-expanding cast undermines confidence in exchanges’ longevity. China is looking for stock markets that will spur the economy. For that, more is not merrier.