IN RECENT years China’s economy has obeyed a three-act dramatic structure, recognisable to any playwright. Growth starts the year brightly, suffers troubling setbacks as spring turns to summer, then prevails in the end, after a hurried government stimulus helps it meet the official GDP target, with precious little to spare.

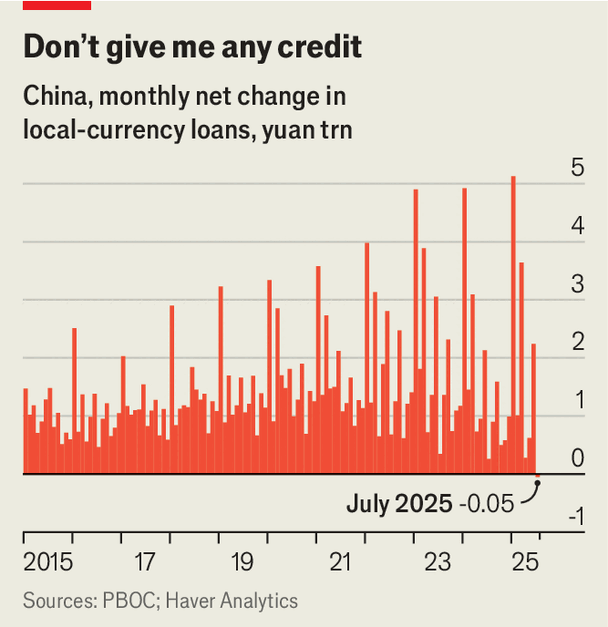

This year’s difficult second act has now begun. After reporting brisk year-on-year growth of 5.3% in the first half of 2025, China’s statisticians have just released disappointing figures. Retail sales grew by only 3.7% in July compared with a year earlier, before adjusting for inflation. The volume of home sales fell by 8% over the same period. Households were so reluctant to take out mortgages, or any other kind of credit, that the yuan loan books of China’s banks shrank in July for the first time in two decades (see chart).

The job market also looks wobbly. Urban unemployment, which does not count people who retreat to the countryside when they cannot find work in the cities, edged up from 5% to 5.2%. And things may get worse. China’s highest court has recently ruled that employers cannot waive pension contributions (and other social-insurance payments), even if workers want them to. The ruling could raise the cost of labour by about 1% of GDP if enforced, according to Société Générale, a bank.

Contributing to the slowdown, China’s policymakers seem to be keeping tighter tabs on its flagship stimulus policy—a scheme that encourages households to trade in old cars, phones and appliances for new ones. The central government did not rush to replenish funds when several local authorities recently exhausted the latest instalment of money that was set aside for the scheme.

The purse-strings have also tightened for officials themselves. In May the government revised regulations on “promoting frugality” and “opposing extravagance” among government and Communist Party workers. “Working meals must not include high-end dishes, cigarettes or alcohol,” it decreed. That may have damaged China’s once booming schmoozing sector. On August 8th a commentary published by Xinhua, an official news agency, acknowledged worries that the revised rules were harming motivation and curbing consumption. Such concerns, it said, must be viewed “dialectically”. The word is a nod to Marx and Hegel. Alas “The Phenomenology of Spirit” is a poor substitute for the phenomenology of spirits.

Curtain up

If China’s economy is to triumph again in its third act, hitting the government’s growth target of 5% for this year, it will need more stimulus. The government has recently announced a variety of measures to help. Families will now get 3,600 yuan (about $500) a year as a childbirth subsidy, for each sprog under the age of three. From the start of this autumn term, they can also enrol their children in the final year of a state pre-school free, or collect an equivalent subsidy for a private one. The elderly with moderate to severe disabilities can get a monthly voucher worth up to 800 yuan to pay for care. Employers who hire unemployed young people will also get a government payout of up to 1,500 yuan.

To boost banks’ loan books, the central government will subsidise consumer credit for the first time. The new policy, released on August 12th, will shave one percentage point off the interest rate for small personal loans and also subsidise bigger loans for cars, elderly care, education and training, childbirth expenses, culture and tourism, home furnishings, electronics and health care.

Unlike China’s traditional efforts to lift demand, these measures encourage consumption, not investment, and emphasise the purchase of services, rather than things. “These new programmes show the government becoming more comfortable with income transfers to households,” Ernan Cui of Gavekal Dragonomics, a consultancy, has pointed out. And the handouts are not confined to the poor.

But though they are novel, these transfers are small. The childbirth payouts and consumer-loan subsidy will each add less than 0.1% to GDP this year, according to Goldman Sachs, another bank. If that is not enough to get China’s economy through its mid-year wobble, the government will need to offer additional stimulus. China-watchers expect increased infrastructure-investment growth. One example is a controversial new 2,000km railway between Xinjiang and Tibet. A state-owned firm to oversee the project was formally registered on August 8th.

In the three-act drama that is China’s economy, the government’s new consumer subsidies offer a novel twist. But it may be a stock character—infrastructure investment by state-owned enterprises—that ultimately saves the day. ■

Subscribers can sign up to Drum Tower, our new weekly newsletter, to understand what the world makes of China—and what China makes of the world.

The Economist