Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Good morning. The US producer price index — which measures wholesale prices — landed yesterday, and was way above expectations. It jumped 0.9 per cent from June; the market was only looking for 0.2 per cent. Prices of both goods and services rose. Businesses downstream of producers are starting to bear the brunt of tariffs. Consumers’ wallets can only be so far behind. Email us: unhedged@ft.com.

Defensive stocks

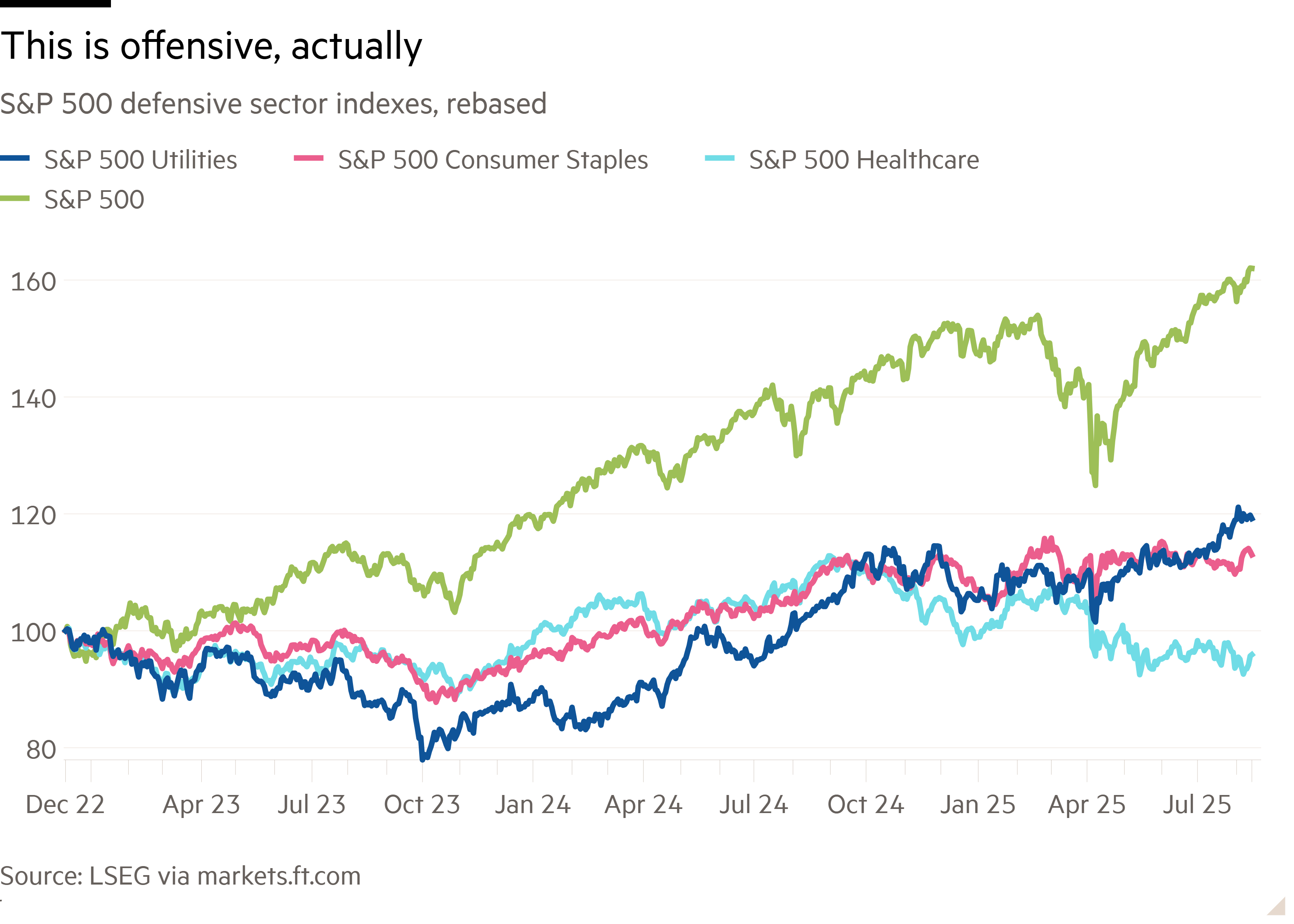

Defensive stocks have been performing terribly for a long time. Below are the three canonical defensive sectors of the S&P 500 — utilities, staples and healthcare — since the market bottomed at the tail-end of 2022. Yuck:

There is, in one sense, nothing surprising about this at all. Since inflation peaked in 2022, equities have been a growth market and a tech market; everything else has trailed. Add to this the political worries surrounding healthcare under Donald Trump’s administration, and underperformance is what one might expect. But the situation has hit an extreme.

In a note to clients, Ryan Grabinski of Strategas provides a way to measure the extremity: comparing the sector weight of the defensive sectors within the wider index (that is, their market capitalisation, which is largely a function of stock prices) with their earnings weight (the contribution of their earnings to the total earnings of the index). Unusually, the sector weight has now slipped below the earnings weight. In other words, earnings are holding up better than price performance would suggest. Chart from Grabinski:

Alarmingly, Grabinski points out, the recent collapse in sector weight relative to earnings weight closely parallels what happened to the sectors in the run-up to the bursting of the dotcom bubble in 2000 (as you can see in his chart).

Unhedged likes to think of performance in the context of growth rather than levels. Looked at that way, the story is quite different for the three sectors. Over the past four quarters, average sales growth and operating profit growth for the staples sector has been 2.4 per cent and 1.6 per cent, according to data from S&P Capital IQ; for utilities, 7 per cent and 11 per cent, and for healthcare, 10 per cent and 11 per cent. Utilities and healthcare are seeing decent growth, while staples are struggling with weak demand and pricing (as we have discussed in this space before).

Time to look for bargains in healthcare and utilities, then? Healthcare might be the better bet: the sector is almost four times larger than utilities by market cap, providing a wider field of choice. And the health sector’s price/earnings valuation is at the low end of its historical range, whereas the utility sector is near the top. Happy hunting.

(Armstrong)

China deflation

China’s economy has had a decent few months. While the housing market remains in distress and factory surveys reflect real strains, there have been reassuring signals. The government has put money behind consumption stimulus schemes, to good effect. Growth was solid last quarter. And exports to the US have bounced off their lows:

The good news may not last, however. The big worry is deflation. The headline consumer price index slid back down to zero in July:

Core CPI rose, but that may have been a mirage. Leah Fahy at Capital Economics notes there has been little sign of inflation outside of goods covered by government-sponsored trade-in schemes. Her chart, showing the year-over-year changes in the value of goods sold by large retailers:

China’s economy is suffering from neijuan, or involution — excessive price competition which feeds deflation and ultimately weakens demand. Talk about Chinese state-sponsored overcapacity tends to focus on high tech products such as electric cars, and what the country’s output implies for western competitors. But the nation’s overcapacity is pervasive — particularly in materials and other inputs to its once-booming housing sector. It is a threat to Chinese companies and households, too.

Those pressures appear to be increasing. In June and July, China’s producer price index had seen big year-over-year declines:

And the economic green shoots may be wilting. Exports to the US are falling again; Torsten Sløk at Apollo notes shipping container departures from China to the US have collapsed since June. And, according to Fahy, the government had used up more than half of its budgeted stimulus funds by late June. Unless the programmes are expanded, there will be less support for the rest of the year. “There will be some soft patches in the next two quarters,” warns Rory Green at TS Lombard.

Recent comments from officials suggest the government is alert to the problems. But absent more stimulus and structural reform — ending state support for favoured companies and industries, encouraging companies to consolidate — deflation will continue. Some even argue government efforts to curb overcapacity could make things worse. From Dan Wang at the Eurasia Group:

Deflation will be a permanent rather than transitory phenomenon . . . Policymakers are still in favour of emerging industries and their supply chains, so there is no incentive for anyone to exit the market. If [a player is forced out] of the market, existing players will expand their capacity as aggressively as possible to capture more market share . . . It will cause more deflation, not less.

Chinese equities appear unfazed. Shanghai A-shares are near a two-year high:

That seems out of tune with the deflation threat. But, as ever, it is important not to equate the stock market with the economy. China’s tech and telecoms industries are thriving. And Trump’s recent deal to allow high-end chips to be sold in China, and the prospect of more concessions in negotiations, has raised bullishness on Chinese AI.

This rhymes a little with the US market, with its narrow, tech-fuelled exuberance in the face of rising concerns over growth and inflation. But a rising stock market does less for China than it does for the US. Wang says: “The stock market boom could bring higher inflation, but since less than 1 per cent of Chinese household wealth is in stocks, the boosting factor is quite limited.”

(Reiter)

One good read

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.