Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

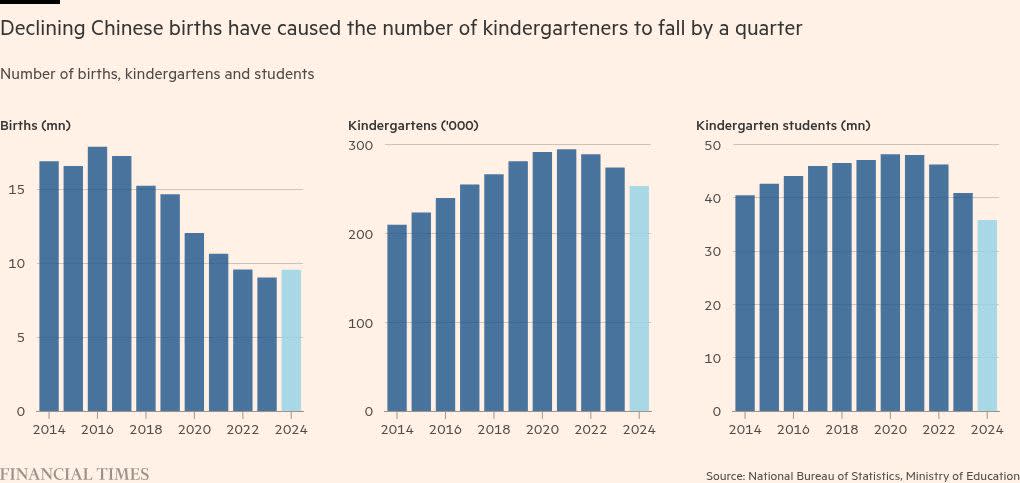

The number of Chinese kindergartens has fallen by a quarter in four years, prompting the closure of tens of thousands of schools in the country as a precipitous drop in births hits the education system.

Enrolments in China’s kindergartens have declined by 12mn children between 2020 and 2024, from a peak of 48mn, according to data from the country’s ministry of education. The number of kindergartens, serving Chinese children aged 3-5, has also fallen by 41,500 from a high of nearly 295,000 in 2021.

Falling enrolments are now “baked into the system and that’s not going to change”, said Stuart Gietel-Basten, director of the Center for Aging Science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. He added that compared with five or 10 years ago, the decline in births was “huge”.

The contraction of China’s pre-school system is a foretaste of the challenges to come for business and policymakers from China’s demographic decline, which is expected to be one of the most rapid in the world.

China has recorded three consecutive years of population decline to 2024 following the decades-long policy, ended in 2016, that limited many couples to one child.

While the number of births rose by about 520,000 last year to 9.3mn, following a record low in 2023, they were still outpaced by deaths and have declined by nearly half since the peak of 17.9mn in 2017.

Zhuang Yanfang, an educator and owner of three kindergartens in Jinhua, a city in China’s prosperous coastal Zhejiang province, decided to turn one of her facilities, which at its peak had boasted 270 children, into a 42-bed nursing home in 2023.

“With the birth rate dropping, enrolments had declined,” said Zhuang. She estimated that “90 per cent of private kindergartens have closed” in the rapidly ageing community.

Despite expanding her two remaining kindergarteners to provide day care for infants starting from 10 months old, she was not optimistic. The facilities had only about 150 children combined, down from more than 1,000 a few years ago.

Some see opportunities for reforming China’s education system in response to the demographic cliff. HKUST’s Gietel-Basten said that Beijing could reallocate resources saved by the declining student numbers to improve the overall quality of the education system, from providing better day-care facilities for infants to investing in its universities.

It could also revamp systems such as the gaokao, the notoriously demanding university entrance exam that determines a student’s chances of entering the best schools.

“All of these aspects have to be reformed in order to allow this smaller, older but more educated, more skilled and healthier population to really thrive,” he said.

He noted, however, that the question of what to do with the vast infrastructure of China’s education system, such as the buildings and properties, was more difficult.

Even Zhuang, the kindergarten operator, has found that the transition to running nursing homes has its own challenges.

Her new facility houses just 16 people, though in addition to beds, it offers services such as social activities and a canteen to about 200 retirees in the community.

She said most elderly people, who prefer to live with younger family members, would only stay in a nursing home as a last resort, “especially when they are in good physical health”.

“We are looking at how we can get through the next few years,” said Zhuang. “Some people would choose just to shut them down . . . but we are hoping to keep them going, for old times’ sake.”