Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Chinese economy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

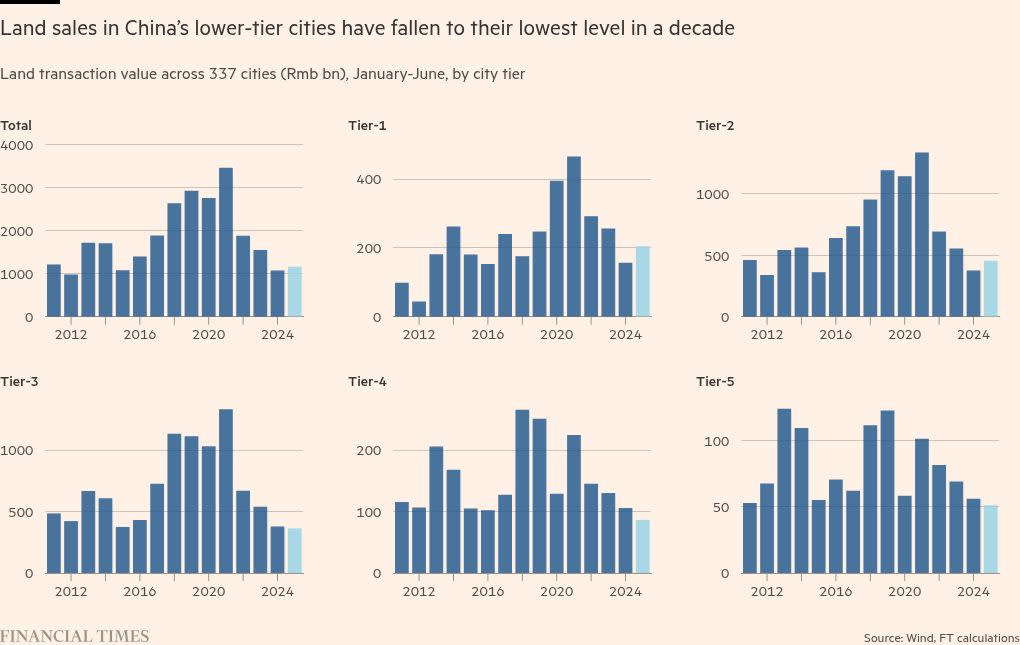

Land sales across smaller and less wealthy Chinese cities have fallen to their lowest levels since at least 2011, highlighting the bleak prospects for a full recovery across a national real estate market mired in a slowdown.

Data from financial information provider Wind shows the total value of all land transactions in third-tier mainland Chinese cities, as ranked by population and economic development, fell 4 per cent to Rmb362bn ($50bn) in the first half of this year on the same period last year, despite a slight rise in sales for residential use.

The value of land transactions, including for residential, commercial and other uses, slipped to Rmb87bn in fourth-tier cities and Rmb51bn in fifth-tier cities — both also the lowest since Wind began compiling the data series in 2011.

The data showed that across 337 cities in China, sales rose 8 per cent to Rmb1.2tn in the first half, fuelled by increased activity in first- and second-tier urban areas. But after a collapse in volumes that began in 2021, the total was still the fourth-lowest recorded by Wind.

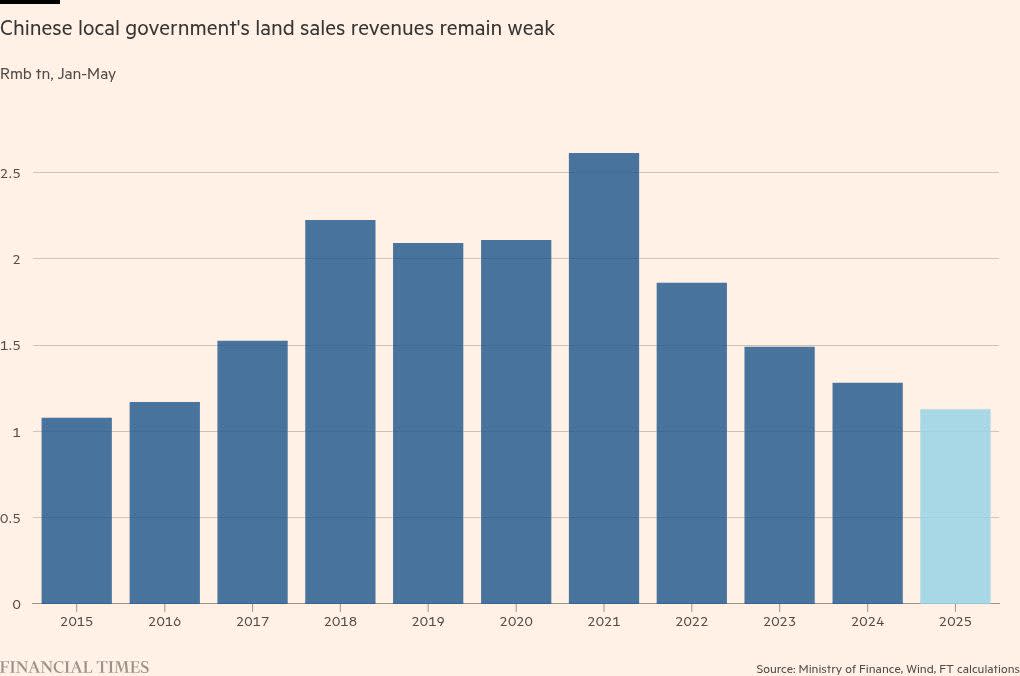

The worsening picture outside the largest and wealthiest cities points to the challenge for policymakers in Beijing as they try to revive a real estate market that for years anchored economic growth and provided local authorities with vital revenue.

“I think the issues will be persistent,” said Jeff Zhang, an analyst at investment research company Morningstar, pointing to “suppressed demand” in lower-tier cities, where developers were unwilling to use their land banks while still offloading existing properties. “There is a huge inventory of homes that is already there”.

China’s property market has struggled to rebound from a slump now well into its fourth year. New home prices across 70 cities dropped 0.3 per cent month on month in June, despite a host of government measures aimed to restore confidence and recent signs of a slower pace of decline in richer urban areas.

Lower-tier cities, where governments often rely on land sales for revenue, are seen as particularly vulnerable to excessive housing supply following a construction boom that spectacularly imploded in 2021.

Beijing has launched a series of measures targeting mortgage rates to boost demand, as well as pushing for the completion of unfinished projects and pledging to convert unused properties into social housing. Last year, Goldman Sachs estimated that China had Rmb30tn of unsold housing inventory, including land and completed apartments.

Ting Lu, chief China economist at Nomura, said in a report this month that despite government efforts to support the market last September, “the downward spiral in low-tier cities [is] almost unchanged”. A high proportion of land sales now took place in just 10 cities, he added.

State-owned developers have focused heavily on the first-tier cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, where the Wind data showed land sales rising 30 per cent year on year by value in the first half of the year. Analysts at HSBC have said “high-end markets are thriving”.

But in lower-tier cities, the contrast is sharp.

“I don’t think any major developers will go into those cities,” said Lulu Shi, an analyst at Fitch ratings, of weaker third- and fourth-tier areas. “The only remaining developers that do business in those cities are local ones, and most of them are constructing existing projects,” she added.

In a report on China’s property slowdown, Goldman Sachs analysts said they expected “substantial regional divergences”. The US bank forecasts “broad property price stabilisation” in higher-tier cities by the end of next year.

Land sales are an important source of income for local governments. Official data shows that Chinese local governments’ income from land sales fell 12 per cent year on year to Rmb1.1tn to the end of May, the lowest level since 2016.

“The actual slump could be much worse than the reported data suggest,” said Nomura’s Lu, who estimated that the “lion’s share” of land purchases was by local government financing vehicles — state-owned companies that borrow to invest in real estate.

“Essentially, local governments have been selling land to themselves to stabilise local land markets, especially in low-tier cities that are unable to attract real bidders other than their own LGFVs,” he said.