Good morning. Weekly jobless claims fell last week, the US labour department reported yesterday. While the lower-than-expected number looks reassuring, it may have been due to seasonal quirks — fewer US auto plants shut down this year than in a typical summer, according to multiple economists. Meanwhile, the rise in continued claims indicated that hiring is slowing. The labour market is still holding up, but we worry that some small cracks might become bigger. Email us: unhedged@ft.com.

Friday Interview: Michael Froman

Michael Froman is president of the Council on Foreign Relations. He served as US Trade Representative in the Obama administration and in a variety of senior economic positions in the Clinton and Obama administrations. We spoke with him about the latest news on tariffs, the US-China relationship and the outlook for global trade.

Unhedged: It’s been an interesting few weeks of tariff news: threats on Brazil, higher tariffs on Japan and Korea and new information on EU tariffs. How are you thinking about the tariffs? Where are we? Where are we going?

Michael Froman: I think President Trump views tariffs as a critical policy tool. He sees them as a source of leverage, whether that’s over fentanyl or migration, the Brazilian judicial system, or, as of this week, a way to push Russia into a deal on Ukraine. He sees them as a source of revenue — we’ve actually seen a significant increase in tariff revenue in the first six months of this year. And he sees them as a way of driving manufacturing back to the US and incentivising companies to move their supply chains here.

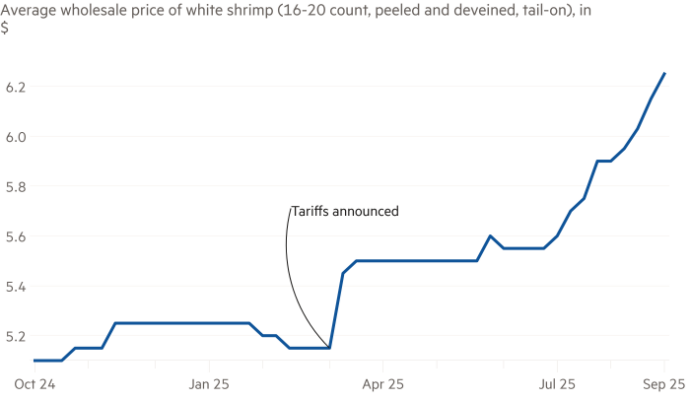

So the direction of travel is certainly that we’re going to end up with higher tariffs than we had back in 2017. We’ve already gone from around a 1 per cent effective tariff rate to something closer to 16 per cent. And, if higher tariffs get implemented on August 1, we’ll get close to 20 per cent. But this will all depend on whether he’s successful at achieving the various objectives that he’s laid out.

Unhedged: It seems like the market has settled around believing the US will end up somewhere in the ten to 15 per cent range, and the market has seemed OK with that. It sounds like you are saying tariffs will be higher. Is the market wrong to be dismissive?

Froman: I think the overall rate is likely to be higher. Ten to 15 is the range we’d get if there is a baseline rate applied to all countries at a minimum. But then you will have sectoral tariffs on top of that — steel, aluminium, autos and so on. And then you have countries that are going to be well above the baseline, including China. Adding that together, I think we end up closer to the 16-20 per cent range, depending on what the president’s decisions are. According to the Yale Budget Lab, that could result in something like $2,400 in increased costs per household. That has real effects.

The question is: what are we getting for that increase in costs? Hopefully, we’re getting stronger national security and more good-paying jobs. But I think that’s very much open to question. Even if tariffs lead to some companies building new factories or expanding their factories in the US, you may find downstream industries that are adversely affected. For example, the Trump administration imposed tariffs on steel in 2018. Looking at the data a few years later, we had 1,000 more steel workers than we had in 2018 — but we had 75,000 fewer manufacturing workers in industries that use steel.

And, in terms of revenue, there’s an inconsistency. If we’re successful in moving production to the US, then we’re going to be importing less and collecting less tariff revenue. But, if we’re collecting a lot of tariff revenues, it means we’ve failed to move production back to the US. You can’t really have success on both dimensions.

Unhedged: A lot of the “deals” and new tariff policies we have been getting could fit on the back of an index card. As somebody who’s negotiated detailed trade deals, what’s being lost in this process? What are the risks when trade policy is done this way?

Froman: Well, we haven’t seen the agreements, with the exception of the UK. And even the UK agreement was only alignment on a few trade items, and an agreement to continue to negotiate on the rest. There’s a lot of details to be implemented even within a fairly simple tariff agreement. For example, what constitutes a product from a country, what we call the rules of origin? How much of that product has to be made in that country? What kind of transformation of the inputs needs to be done in that county for it to count?

This is important, because the administration has indicated to various countries that they may have a tariff rate of X per cent, but they could have a tariff rate of X plus 20 if they are being used as a transshipment country for exports from China. So, for a factory in Vietnam that has Chinese inputs, will its goods count as Chinese or Vietnamese products? There is normally a very detailed negotiation over these questions. But those have yet to happen. And, in Vietnam’s case, reporting suggests that the Vietnamese claim there actually isn’t a deal, because the US president announced a tariff rate that was substantially higher than what the Vietnamese thought they negotiated.

Unhedged: You led negotiations of the Obama-era proposed investment treaty with China, which was scrapped by the first Trump administration. What do you make of the China “deal”?

Froman: From what we can tell, it’s not a trade agreement. It is a ceasefire in what was a series of escalatory measures this year. China has discovered the areas where it has leverage over the US, including minerals and magnets, and it imposed some additional export controls on those products in response to the US tariffs. The US then imposed export controls on China. What they agreed to in Switzerland was to stand down from those export controls.

But it did not deal with any of the fundamental issues in the US-China relationship: excess capacity, subsidisation of state-owned enterprises, theft of intellectual property rights or any of the other matters that have been central to the tension between the US and China. There is much more work to be done, but at least it created a path to de-escalation.

Unhedged: Where do you think things will go from here?

Froman: The US spent decades trying to engage with China and encourage them to pursue economic policies that would allow them to achieve significant growth, but not at the expense of the rest of the world. We had only modest success. Then the first Trump administration came in and said that rather than trying to negotiate a change to China’s economic strategy, the US is just going to ask China to buy more of our stuff. In 2020, we agreed that they would buy more US LNG and agricultural products. There were other elements of the package too, but, effectively, it was more of a purchase and sale agreement than a true trade agreement. China initially failed to implement its commitments in part because of Covid, but they still haven’t bought the levels of US exports that they had promised to.

Now the question is: where will we take the relationship? Is there going to be another agreement where it’s all about selling them more US products? Or is it going to be about reforming elements of their system, with an agreement saying it’s unacceptable for China to subsidise excess capacity? We don’t really know where the Trump administration stands.

Unhedged: China’s growth strategy seems to be focusing on exports. Without the US, they need to rely more on Europe and other regions. Do you expect that the Europeans and others will push back?

Froman: The Europeans have already begun to put up barriers to Chinese exports. But they will be more reluctant to do so than the US, because they are more committed to the multilateral rules based system. They will not announce 50 or 100 per cent tariffs willy-nilly. But they will see a more significant impact on their manufacturing pace as a result.

China is building enough excess capacity to basically build every car that’s needed in the world. They’ve got to send those cars someplace, and how many EVs can India, Brazil or South Africa absorb? If Europe actually shuts them out, where will that excess capacity go? This will be a real challenge for China and its trading partners.

Unhedged: Before Trump was elected in 2016, higher trade barriers and less “free trade” was more a Democratic policy than a Republican policy. The Biden administration kept a lot of Trump’s tariffs on the books and raised others. Given that Trump has taken us past this immense threshold, are we now beyond the point of no return?

Froman: Tariffs tend to be sticky. They are easy to put on and hard to take off, because once they’re on there are constituencies that are strongly in favour of maintaining them. And there is a political cost to reducing them, particularly reducing tariffs on countries like China. So there is the possibility that we’ll see a ratchet effect.

I think the counter-argument is if the tariffs leave a significant negative impact on the economy. If people feel the tariff inflation — and we saw the role that inflation played in the last election — and if we see slower growth in good-paying jobs than we have seen over the last couple of decades, there could be a negative reaction to tariffs, or how the Trump administration used them. But I don’t think the pendulum will swing all the way back to where we were in 2016.

Unhedged: We’ve seen the dollar come down over the past couple of months. What do you make of the dollar’s fall? What does that say about broader global flows as they’re related to tariffs?

Froman: So far this year the dollar has declined by ten per cent. And the administration has been of two minds as to whether it wants the dollar to remain the reserve currency of the world, which comes at a certain cost, or whether it wants a weaker dollar to help promote additional exports, particularly manufactured goods.

I think one issue is, whatever the value of the dollar, we’re only going to see US exports go up if the rest of the world is growing. So to connect the dots between tariffs, policy and dollar value is to say: if these tariffs reduce global growth, we’re going to see less demand for our goods, almost regardless of what the value of our currency is.

I think that speaks to a broader issue for the administration. Oftentimes, the administration has multiple policy objectives and doesn’t seem to connect the dots between them. It will take an action on one domain that actually makes it more difficult for them to achieve their objectives in another. We want to beat China, be number one and remain the most innovative and vibrant economy. But part of that is our commitments to research and development, a strong university system and the rule of law. All of those commitments are under stress.

Unhedged: What else is on your mind? What trade policy questions are you trying to get more clarity on?

Froman: I think one of the big unanswered questions is: how do we view our allies and partners in the world? You can have a trade war with China, but it’s hard to have a trade war with China, Canada and the EU all at the same time. This speaks to the administration’s unwillingness to connect the dots across its priorities.

The administration may also be right that consumers ought to be willing to pay more to be less dependent on China. And I think that is particularly the case where you can link the tariff to a product that is important for national security. But across the board tariffs make most things more expensive, even when it’s not strategic. Why should we make T-shirts in the US? That seems like we are not taking the trade-offs as seriously as we should be.

Finally, the focus of the administration has been entirely on goods. But 80 per cent of our workforce is in the services sector. We are a net services exporter, and so much manufacturing in the future also depends on services like software. The data on services is not as clear as it is on goods, and some services exports actually reflect companies taking advantage of other countries’ lower tax rates. But we should be paying more attention to the services side of the ledger.

One good read

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.