Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Chinese economy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is chair of Rockefeller International. His latest book is ‘What Went Wrong With Capitalism’

The great half-truth about China is that its economy consumes too little and invests too much. Over-investment is a real problem, but underconsumption is not. So the mounting calls on the country to “rebalance” by encouraging more consumer spending are misguided. In the standard telling, China set out to become a manufacturing power in the 1980s and has since suppressed spending by consumers, so it could pour their savings into building ports and factories. But the suppressed consumer is a myth.

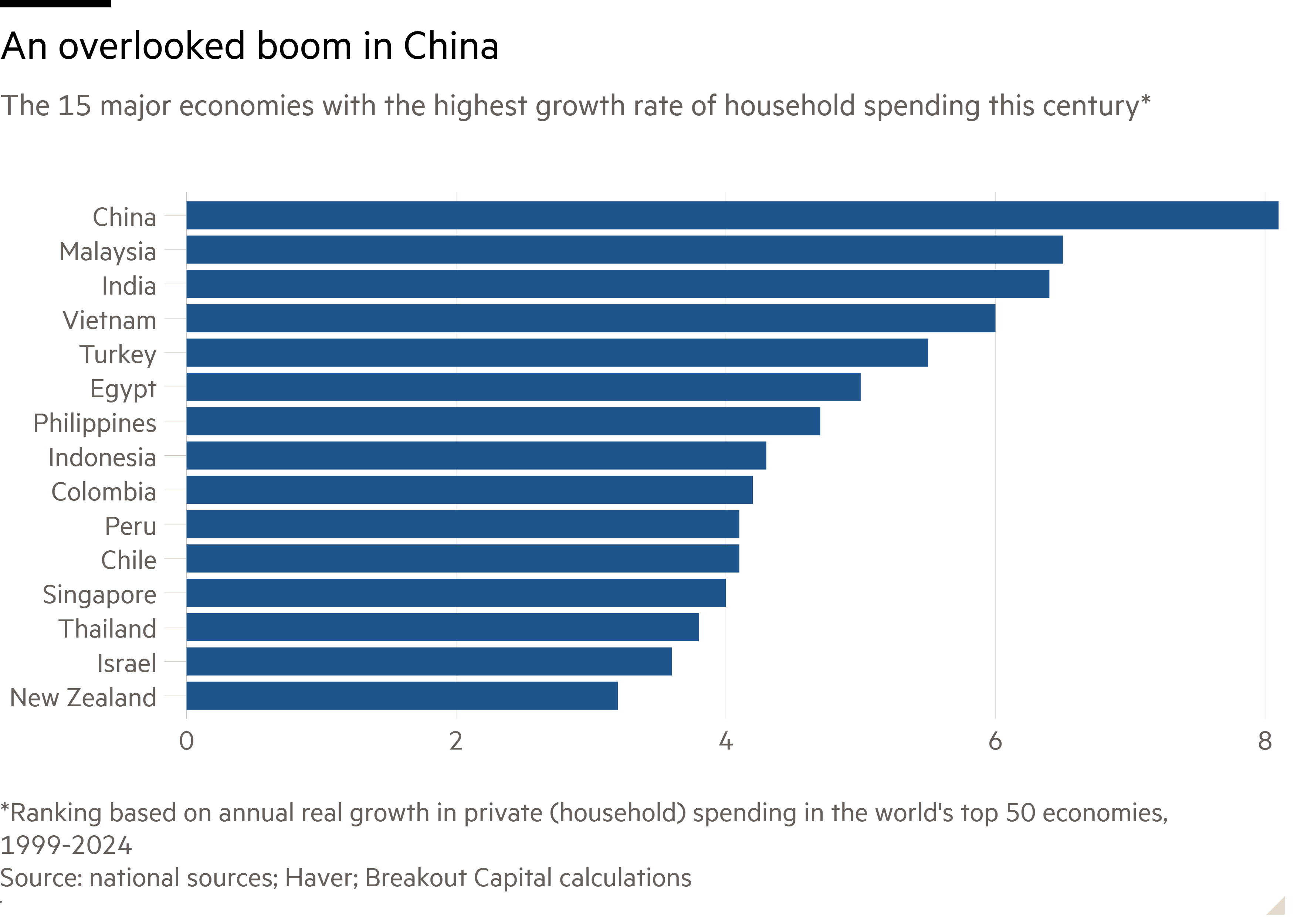

So far this century, in real terms, private consumer spending in China has grown more than 8 per cent a year, faster than in any other economy — by far. Over the past few years, consumer spending growth has slowed in most countries, due to ageing populations and falling real incomes, and it has fallen in China as well to 5 per cent a year. But that is still higher than in any other major economy except Turkey, where consumption was boosted by a credit boom and refugee inflows.

The myth rests in good part on the consumption share of China’s GDP, which is just 40 per cent — well below the global norm. But the reason for this anomaly is not that consumption has grown slowly, it is that the other big component of GDP, investment — in infrastructure, real estate, export industries — has grown even faster, averaging 10 per cent a year in this century.

That pace, too, is the fastest for any major economy by a significant margin. Corrected for this long-term pattern of over-investment, the consumption share of China’s GDP would be around 55 per cent, closer to normal.

Consumer spending has also grown much faster in China than in established and newer Asian manufacturing powers, from Japan and South Korea to Indonesia and Malaysia. And when the original miracle economies were reaching the level of development in China today, they too saw sharp slowdowns in consumer spending growth.

Yet, somehow, calls to free the Chinese consumer persist alongside mounting evidence of the steady growth in their spending. It’s difficult to spot symptoms of repression among the Chinese shoppers in luxury stores from Shanghai to Paris. Drill down into consumer spending, and growth looks to be weakening mainly for services, not goods. But this, too, is partly illusory. If one factors in services provided by China’s government at little or no charge, including healthcare and education, consumption rises significantly as a share of GDP.

Investment, on the other hand, is clearly excessive at 40 per cent of GDP and roughly equal to consumption. In a typical economy, investment is lower than consumption as a share of GDP but more important to the economic cycle. Consumers can’t stop spending on necessities in a downturn but businesses can stop investing, at least for a while.

This binge has been extreme. Only 10 countries have ever seen investment peak above 40 per cent of GDP, briefly. At that level, so much capital flows to unnecessary projects that the binge tends to reverse quickly, slowing growth. China, uniquely, has managed by debt engineering to keep investment above that for two decades now.

Relentless over-investment is fuelling tension with trading partners, since China ends up exporting a lot of its excess production, and breeding dysfunction at home. Over time, such binges tend to divert capital into less productive targets such as real estate — which helps explain China’s debt-soaked property market today.

The outsiders urging China to focus instead on the consumer can cite genuine “structural” obstacles to their spending. Internal migration controls block many rural Chinese from moving to higher paying urban jobs. Meager pensions compel many workers to save for retirement rather than spend. The weakening real estate market and other negative “wealth effects” further discourage spending.

China’s leaders seem to be heeding some of this advice. An “action plan” announced in March promised to “vigorously boost consumption”, but so far the action has been light on structural reform and heavy on subsidies for purchases of goods such as home appliances — which have only a passing effect. Consumers rushing to buy rice cookers now won’t be buying them in coming years.

China’s consumer spending has been growing at a world-beating pace and doesn’t have much room to accelerate, particularly not when many households are deep in debt. That debt has tripled in the past 15 years to over 60 per cent of GDP, among the highest in emerging markets and close to that in the heavily consumer-driven US economy.

The country can’t solve the real problems caused by over-investment — from geopolitical tensions to dysfunction at home — by attacking the phantom problem of underconsumption. The crux of the imbalance is that the state has been pushing too much investment for too long in the name of hitting its inflated growth target, now set at 5 per cent.

The answer is not to shift the focus of state meddling to boosting consumption. It is to accept that China is weighed down by a shrinking population, declining productivity and a huge debt load. It has a real potential growth rate closer to 2.5 per cent than 5 per cent. And as growth slows to a more realistic pace, consumption will naturally expand as a share of the economy.