The election of Donald Trump in 2016 was a watershed moment for Bao Phung.

His family’s business A&M Flooring, a Vietnamese producer of premium wooden flooring, had initially struggled to compete against Chinese businesses when it was founded the year before.

But after Trump came to power and unleashed a trade war on China, Bao saw A&M’s business flourish as American buyers rushed to source products from elsewhere.

Profits rose even as local competition increased. Bao says dozens of Chinese companies have moved to Vietnam to avoid US tariffs, estimating there are now 20 times more competitors than a decade ago.

As trade tensions between the US and China lingered during the Biden administration, business remained good. The US accounted for 95 per cent of the company’s total sales — until April 2.

On Trump’s so-called “liberation day”, he announced Vietnam would face a 46 per cent tariff rate, one of the highest in the world. For A&M and its 120 employees, new orders from American clients slowed to a trickle. Like thousands of companies across Vietnam, it is now frantically trying to figure out its future.

“Some of us [in the industry] are trying as best as we can to diversify,” says Bao, A&M’s assistant director. The company is seeking new customers in Japan and Europe. “But other than that, right now, we are on our hands and knees to pray that the negotiation between the US and Vietnam goes well.”

Vietnam was one of the biggest winners from Trump’s first term as manufacturers moved production in droves to the country as part of their “China plus one” diversification strategy.

The country’s recent economic success — with GDP growth at 7 per cent last year — has been driven primarily by exports to the US and surging investments from companies fleeing China. Foreign direct investment in Vietnam surged from $15.8bn in 2016 to $38.2bn in 2024, and it has become a critical link to global supply chains, hosting manufacturing heavyweights such as Apple, Intel, Samsung and Nike.

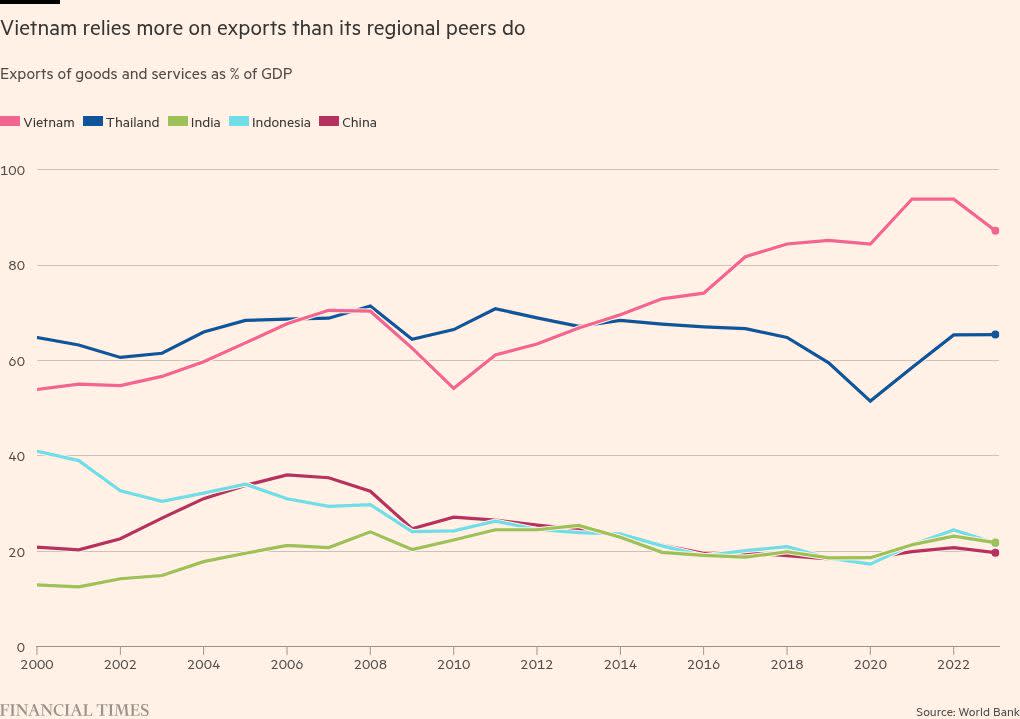

As a result, the south-east Asian country is one of the most trade-dependent countries in the world, with the US accounting for nearly a third of its total exports.

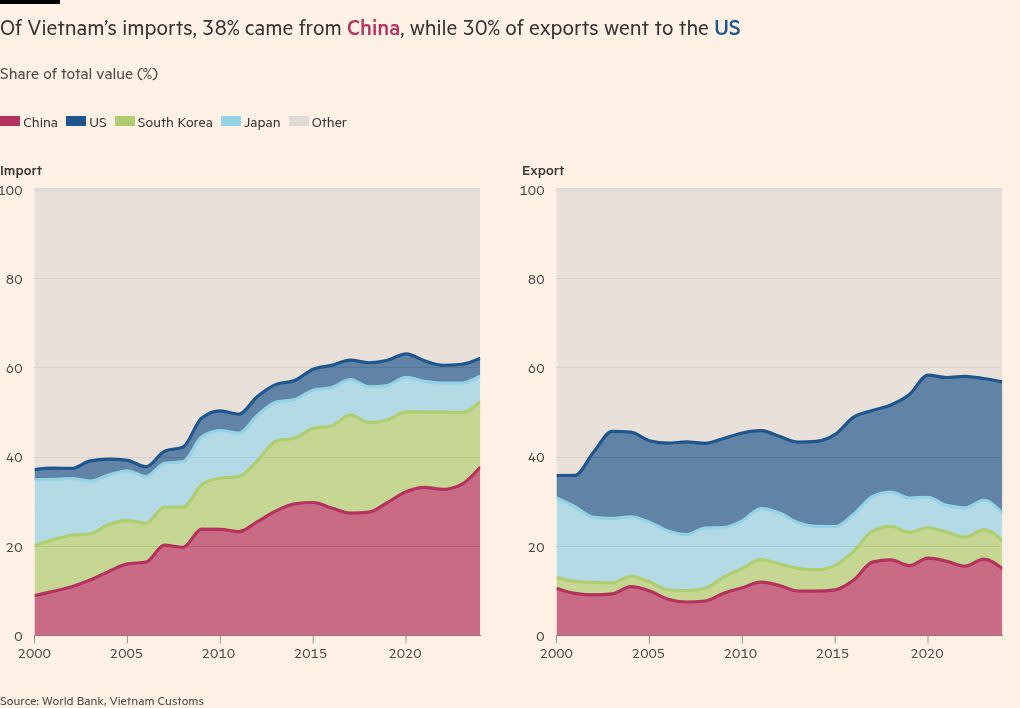

Now, its “China plus one” success has backfired as the US president takes issue with trading partners who have large surpluses with the US. Vietnam has the third largest, after China and Mexico.

Vietnam’s ruling Communist party is acting with urgency to address the tariff threat. Party chief To Lam was one of the first world leaders to call Trump after the “reciprocal tariff” announcements, promising to remove all Vietnamese tariffs on American goods.

But Trump’s actions have also served as a wake-up call — for local factories relying on the US, for American companies sourcing from Vietnam, and for the Communist party — about the vulnerability of the Vietnamese economy to external shocks.

Many now fear its export-led growth model will soon run its course, throwing a wrench in Vietnam’s plans to become a developed country by 2045. In late April, the World Bank revised Vietnam’s growth forecast for this year down from 6.8 per cent to 5.8 per cent.

“Vietnam suddenly woke up on April 3 and realised that if they continued to rely on one single export market in the US, they might be very vulnerable, be it under Trump or under another president,” says Nguyen Khac Giang, a visiting fellow at Singapore’s Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute.

Vietnam should not only diversify trade partnership, he adds, “but also think about how to really build its domestic economy much stronger and to make it more resilient to external shocks”.

Accordingly, the government is fast-tracking economic reforms, with an eye on prioritising the domestic sector.

“Rising trade protectionism . . . is likely to impact our export-driven model,” says Long Pham Vu Thang, head of macroeconomics research at HSC Securities. “The Vietnamese government [is] trying to diversify from that type of risk by finding a different growth model” through institutional reforms, focusing on innovation and high-technology investments, and pursuing growth from the private sector, he adds.

Vietnam has undergone an economic revolution since the civil war ended 50 years ago.

In the postwar period, it pursued a Soviet-style model of a centrally planned economy in which the government controlled all production, trade and prices. The collectivisation of farming, its primary sector, resulted in abject poverty, making Vietnam the poorest country in the world in the early 1980s.

In 1986, the government launched a liberalisation effort called Doi Moi, or “restoration”. The country gradually turned itself into a market-orientated economy by easing rules for foreign investments, removing price controls and export quotas and reducing subsidies for state-owned enterprises that controlled much of the manufacturing.

After a US trade embargo was lifted in 1994, foreign investors began to enter Vietnam to take advantage of cheap labour. In 2001, a bilateral trade deal between the US and Vietnam came into force, opening up the south-east Asian country’s market to American goods and services, and vice versa.

Robert Zoellick, then the US trade representative, hailed the agreement as “an example of how two nations once divided by war can employ trade as a tool to work toward reconciliation”.

Trump’s first term unleashed another transformative wave of foreign investment. Companies looking to avoid the punitive US tariffs on China moved just across the southern border to Vietnam. Strict lockdowns in China during the Covid-19 pandemic prompted more companies to pile into Vietnam.

The country’s investment boom is reflected in the expansion of industrial parks developed by Belgian company Deep C in Vietnam. The company, which operates mostly in northern Vietnam close to the Chinese border, has seen total investments rise from $1bn to $8bn in seven years.

Growth was “fuelled by the fact that Trump won and unleashed the first trade war. Biden did not really tone it down,” says CEO Bruno Jaspaert. The company has been reclaiming land from the sea to accommodate growing demand, much of it for manufacturing.

Vietnam offered more than just a great location. The government was quick to provide incentives on taxes and import duties on raw material needed for manufacturing. Many foreign companies are not required to pay any corporate tax for their first four years in operation.

Foreign investors also faced less red tape than in some of the bigger economies in the region such as Indonesia, which has strict local-content rules and a lengthy bureaucratic process.

The country’s gaps in infrastructure and power supply proved to be little obstacle to manufacturers pumping in record amounts of investment as they fled China due to the high tariffs.

But that also posed a problem: susceptibility to global trade uncertainties. In 2023, Vietnam’s exports-to-GDP ratio was close to 90 per cent — much higher than south-east Asian rivals such as Indonesia (22 per cent) and Thailand (65 per cent), and China (20 per cent), according to the World Bank.

That is why America’s new tariff regime is likely to have an outsized impact on economic growth, jobs and investments. More than half of Vietnam’s total workforce of 57mn is in export industries, according to the World Bank. If 46 per cent tariffs were sustained, the country’s economic growth would decline by 1.8 percentage points this year, according to HSC Securities.

But there is huge uncertainty over the Trump administration’s trade policies. Economists believe Vietnam could end up with a 20-25 per cent tariff rate after intense negotiations with the US.

However, this may rest on Vietnam not only narrowing its trade surplus, but also cracking down on alleged Chinese trans-shipment of goods through its borders.

Even if it does so, higher tariffs will erode Vietnam’s appeal as a centre for exports. “Much of the manufacturing investment entering Vietnam was never intended for its domestic market but rather to establish the country as an export hub, primarily for shipments to the US,” says Marco Förster, Asean director at Dezan Shira & Associates in Ho Chi Minh City who advises investors.

While those who have already invested heavily in the country will probably stay, he says, new FDI could slow down as companies may look at India or south-east Asian countries that have lower tariffs.

“Companies that previously considered ‘China plus one’ production but have yet to act are now reconsidering whether relocating is even worthwhile, especially as tariff gaps with other destinations narrow,” he adds.

Vietnamese companies are already making plans for the worst-case scenario of 46 per cent.

Bao from A&M Flooring says he is thinking about selling his products to the US via another country that has lower tariffs than Vietnam. He is considering sending semi-finished goods to Colombia, for which Trump announced a 10 per cent tariff, and then assembling the final product there to be eligible for the lower tariff rate.

“We do not want to go that route because it’s a logistical nightmare . . . [but] you have to work out [the difference] between paying for the tariffs and paying for the extra logistics.” He also wants to reduce the company’s US dependence from 95 per cent to 30 per cent.

Le Hang, deputy general secretary of Vietnam Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers, says companies in the industry are rushing to find other markets. The US accounts for a fifth of Vietnam’s seafood exports. “Some say they will change direction or diversify the market, but finding a partner is a matter of years,” she says.

American companies are also struggling. Honey-Can-Do, which sells housewares such as drying racks and shelving units, is one of the many companies that shifted production from China to Vietnam during Trump’s first term. It partnered with its Chinese suppliers to co-invest in factories in Vietnam, spending millions of dollars.

It now sources roughly 60 per cent of its goods from Vietnam, from less than 5 per cent in 2017.

“We got the message from President Trump, and it kind of continued under President Biden . . . the signal was ‘China bad, Vietnam and other countries, good’,” says founder Steve Greenspon. “So when the large tariff was announced for Vietnam, it was crushing.”

Honey-Can-Do has cut costs and let go of employees in the US due to the tariff uncertainty, and Greenspon says its suppliers in Vietnam may resort to the same measures to save costs.

Hanoi is also seeking to re-engineer the country’s economic model to make it less dependent on the US.

Economists say bureaucratic and economic reforms under way in Vietnam could blunt some of the impact of the tariffs.

Vietnam is in the midst of a bureaucratic overhaul that is expected to trim the size of the government by a fifth. It is reducing the number of ministries and government bodies, merging provinces and cutting 100,000 jobs.

VinaCapital, an investment management firm in Ho Chi Minh City, says a more efficient government could have an impact on domestic activity, resulting in faster approvals for investments in real estate and infrastructure projects.

“Fortuitously, before all this tariff stuff came up, they were already starting to push the agenda of . . . trying to make the whole machinery of both the private sector and the public sector more efficient,” says VinaCapital’s chief economist, Michael Kokalari.

In addition to the government restructuring, Lam, who took over the country’s most powerful position last August, has also launched an ambitious plan to make the Vietnamese private sector the country’s “most important force”, further shifting away from previous preferential treatment for state-owned companies and the FDI sector.

Through this initiative, Vietnam aims to boost the number of private enterprises in the country from nearly 1mn at present to at least 3mn by 2045. It also wants to foster the creation of 20 large private companies that are integrated into global value chains by 2030. To accomplish these goals, industry figures say the government is likely to deregulate further.

The reforms are seen as part of efforts to help Vietnam avoid the middle-income trap where developing countries see growth stagnate, and achieve developed nation status by 2045.

It is also an effort to address demographic issues, as the country’s working-age population is projected to shrink. This month, Vietnam also lifted its long-standing two-child policy.

“There was already a growing feeling that we have a golden demographic window for the next decade or so, and that we have an opportunity to try to break out of the middle-income trap. And then, of course, the Trump tariff thing has just dramatically accelerated that,” says Kokalari.

For now, though, the government’s focus is firmly on lowering tariffs. Vietnam is set to hold a third round of talks by mid-June.

There is some optimism that Vietnam can strike a deal, given proactive steps taken by the government and the Trump Organization’s growing interest in investing in the country.

The US president’s son Eric visited the country last month to attend a groundbreaking ceremony for a $1.5bn resort outside Hanoi being developed in partnership with the Trump Organization. The company is also in talks to build a new Trump Tower.

Vietnam is also strategically important for the US in the South China Sea as Hanoi has been one of the most vocal opponents of Chinese aggression in the disputed waters.

But Vietnam will also face difficulties meeting US demands to reduce dependence on Chinese raw materials and investments as Hanoi tries to delicately balance its ties with the superpowers.

Despite diversification efforts and reforms, the US will still be an important market in the medium term, says Iseas’ Giang.

“It’s not only about the economic benefits, it’s not only about the state budget, it’s also about social stability in Vietnam, which the Communist party is very concerned with. So this is extremely crucial for Vietnam,” he says.

Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko