The first meeting to break the US-China trade deadlock was held almost three weeks ago in the basement of the IMF headquarters, arranged under cover of secrecy.

US Treasury secretary Scott Bessent, who was attending the IMF spring meetings in Washington, met China’s finance minister Lan Fo’an to discuss the near complete breakdown in trade between the world’s two biggest economies, according to people familiar with the matter.

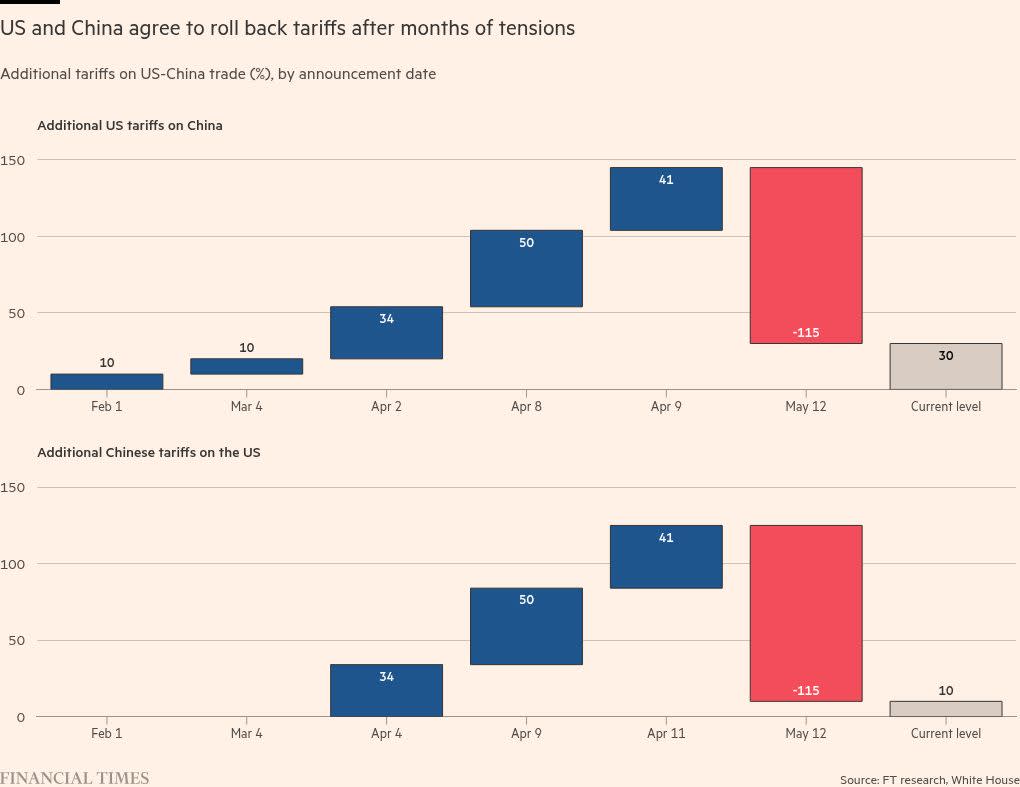

The previously unreported encounter was the first high-level meeting between US and Chinese officials since Donald Trump’s inauguration and the launch of his tariff war. The talks culminated this weekend in Geneva with Bessent and He Lifeng, China’s vice-premier, agreeing a ceasefire that would slash respective tariffs by 115 percentage points for 90 days.

Despite both side warning they were willing to dig in for a long haul, the truce proved easier and faster to agree than expected. One overriding question has significant implications for the negotiations to come: did Beijing or Washington flinch first?

Trump on Monday claimed victory, saying he had engineered a “total reset” with China. Meanwhile Hu Xijin, the former editor of national Communist party tabloid the Global Times, said on social media that the deal was “a great victory for China”.

“The US has chickened out,” said one popular Chinese social media post of the deal.

Economists agreed that the US might have overplayed its hand by raising the tariffs too quickly and too high. “The US blinked first,” said Alicia García-Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist at French investment bank Natixis. “It thought it could raise tariffs almost infinitely without being hurt, but that hasn’t been proven right.”

The US and China had each argued that the other was more vulnerable to the tariffs. But the speed with which they unwound the levies in Geneva suggested that the trade war was inflicting severe pain on both sides, she added.

A hard decoupling of the world’s two largest economies was threatening job losses for Chinese workers and higher inflation and empty shelves for American consumers. Meanwhile, Trump was having to deal with nervous markets in the US and the prospect of empty shelves at big retailers.

Craig Singleton of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a think-tank in Washington, said it was “striking” how quickly the deal had emerged, suggesting that “both sides were more economically boxed in than they let on”.

While Beijing stood toe-to-toe with Washington in fighting Trump’s tariffs, Chinese negotiators still have more work to do to level the playing field; the US still retains much higher tariffs on China than on any other country.

Capital Economics calculated that total US tariffs on Chinese goods would remain at about 40 per cent after the ceasefire while Chinese tariffs on the US would be about 25 per cent. Experts also warned it would be a hard road to secure any agreement that would be more lasting.

“The US-China trade negotiations are going to be like a rollercoaster,” said Scott Kennedy, a China expert at CSIS, a think-tank. “Markets can breathe a temporary sigh of relief but we’re nowhere near out of the woods.”

Ahead of the talks, Bessent had warned that the high level of tariffs was not sustainable and amounted to an effective embargo on US-China trade.

The ceasefire at least narrowed the gap sufficiently for China’s extremely price competitive manufacturers to remain in business in the US.

Alfredo Montufar-Helu, head of the China Center at The Conference Board think-tank in New York, said it would have been impossible for Chinese producers to offset the 145 per cent tariffs imposed by the US. “But at 30 per cent, I think most Chinese imports into the US would regain their competitiveness.”

Before the talks in Geneva, Bessent had said the two sides were unlikely to reach a broad economic and trade deal, saying they needed “to de-escalate before we can move forward”.

But on Monday, he struck an optimistic note, hinting that Washington might be looking for the type of “purchase agreements” that characterised the initial phase of the US-China trade war during Trump’s first term.

These involved Beijing agreeing to buy quantities of commodities, such as soyabeans, and US manufactured goods, but they were disrupted by the pandemic. “There will also be a possibility of purchase agreements to pull what is our largest bilateral trade deficit into balance,” Bessent said.

Bessent and Greer also sounded positive on the possibility of a deal with China to curb the trafficking of fentanyl precursors into the US.

“The upside surprise for me from this weekend was the level of Chinese engagement on the fentanyl crisis,” Bessent said.

He said the Chinese delegation included an official who had a “very robust and highly detailed discussion with someone from the US national security team”.

For Beijing, a fentanyl deal could erase 20 percentage points of remaining tariffs imposed by Trump, placing China roughly on a level playing field with other countries exporting to the US.

China would still face sector-specific tariffs, such as Biden-era levies on electric vehicles. But other countries would also be subject to US tariffs in similar sectors.

Even with this respite, economists cautioned that the bilateral relationship remained troubled, with Trump’s unpredictable policymaking expected to drive China to continue to diversify its exports markets and try to stimulate more domestic demand.

Chinese exporters would also probably use the 90-day window for the negotiation to frontload more exports to the US, which could lead to another surge in China’s trade surplus with the country.

“A durable resolution remains challenging, given the complex bilateral relationship,” said Robin Xing, economist at Morgan Stanley in a note.

With additional reporting by Wenjie Ding in Beijing