Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

China has planted its red flag across Latin America this century, displacing the US as the main trading partner in South America and investing more than $130bn in everything from ports to copper mines.

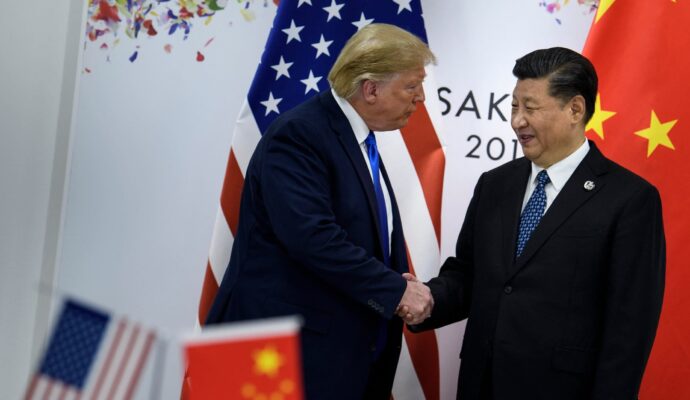

Now the Trump administration is pursuing America First policies such as tariffs and undermining the economic logic of locating factories in nearby countries. Surely Beijing will clean up in what America used to consider its backyard?

Wrong. While China may win a quick boost to its trade with Latin America, there are several reasons why the region is unlikely to draw closer to Beijing over the longer term.

The first is fear of retaliation. Trump has moved aggressively against what he sees as malign Chinese interests in the region. Panama has already felt the heat over Chinese port concessions at either end of the canal; Peru may feel it next over Chancay, its Chinese-built megaport.

“What Trump is looking for is an international order based on spheres of influence,” said David Lubin, a research fellow at Chatham House in London. “The Monroe doctrine defined a sphere of influence for the United States 200 years ago [in Latin America] and the geography of the region hasn’t changed that much.”

Mexico, which depends on the US market for more than 80 per cent of its exports, cannot risk responding to Trump’s tariffs by boosting trade with Beijing. Playing the China card, says Arturo Sarukhán, a former Mexican ambassador to Washington, “would be the death knell of Washington seeing Mexico” as a worthwhile partner.

“The strategy right now from Mexico is: ‘At all costs defend, bulletproof, Teflon-coat the relationship with the US, don’t take on Trump and ensure that the USMCA [trade pact] survives,’” he added.

South American nations fret that they are already too dependent on China. The last thing they want is to increase that dependence further at a time of rising superpower tension.

Data suggests the rapid growth in Chinese trade and investment in Latin America may be over. Last year Chinese imports from the region fell by 0.1 per cent, according to the Inter-American Development Bank, and Chinese foreign direct investment fell last year to the lowest level since 2012, according to a recent study. Pepe Zhang, an expert on China-Latin America relations, believes “the structural decline in Chinese economic engagement in the world won’t change” because of economic weakness at home.

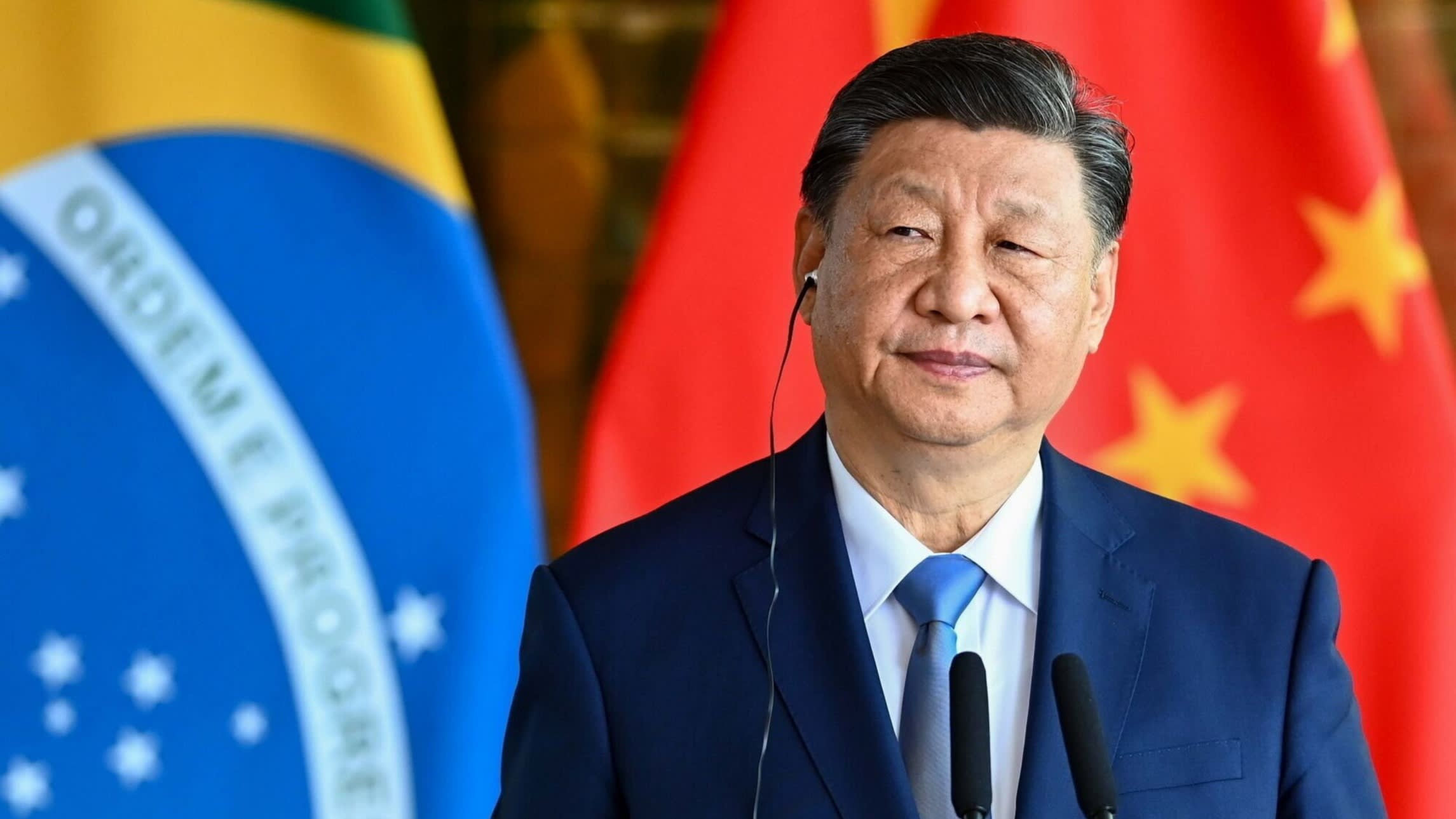

Brazil may increase food exports to China in the short term to fill the gap left by reduced US sales of soyabeans, corn and meat. But “the Brazilian government has always been very cautious about not depending on one big trade partner”, said Feliciano de Sá Guimarães from Brazil’s international relations think-tank Cebri.

Guimarães noted that Brazil’s congress had just given the government sweeping new powers to retaliate against unfair trade practices — measures framed as a tool to hit back at Trump but which could also be used against China.

Cultural issues count, too. Most members of the Latin American elite were educated in the US or Europe and feel little affinity for Beijing.

Rather than picking sides, Latin American nations would prefer to diversify trade. Chile has the highest dependence on China among major regional economies; it is no coincidence that President Gabriel Boric recently travelled to India to open up new export markets.

And Brazil has been pursuing trade with Gulf nations anxious to secure food supplies, while Costa Rica is now seeking membership of the Asia-dominated CPTPP trade bloc.

Finally, the Trump administration is likely to realise that it stands little chance of slowing China’s rise — or sating US consumer demand — unless it enlists Latin America’s help in supplying critical minerals and providing low-cost factories.

JPMorgan’s head of global macro research Luis Oganes, adds: “When prices start to go up in the US and they’re getting the message from companies in the US that what you’re asking is impossible . . . there’s going to be massive pressure to reach a deal with North America to regain some appreciation for the concept of friendshoring and nearshoring. The US will not be able to decouple from China and its North American trade partners at the same time.”