IN HIS ANNUAL New Year’s Eve address, President Xi Jinping struck an unusually measured tone. There was no call for unification with Taiwan, unlike the previous year, and none of the dark warnings about external forces that he voiced at a Communist Party congress in October. “We cherish peace and development and value friends and partners,” he said on December 31st. At home, meanwhile, it is “only natural for different people to have different concerns or hold different views on the same issue,” he added.

Some detect a similar timbre in China’s recent diplomacy, including with Australia and other countries long in Mr Xi’s bad books. The sweet talk has even extended to America. In a Washington Post editorial on January 4th, Qin Gang, China’s outgoing ambassador in Washington and new foreign minister, voiced his appreciation for America’s “friendly and hard-working” people—and its media—as he fondly recalled his exploits there, including riding a tractor in Iowa and throwing the first pitch at a baseball game in Missouri.

The shift suggests to many observers that, as China reopens, Mr Xi is keen to repair some of the damage done to his country’s foreign relations over three years in which it was largely isolated from the outside world and saw attitudes towards it hardening in America and many other democracies. But if Mr Xi’s aim is to undermine his critics abroad and empower those advocating re-engagement with China, there is a critical flaw in the plan: his reluctance to share more complete data on the wave of covid-19 ripping through the country.

After repeated requests from the World Health Organisation (WHO), China has finally started sharing more genetic sequences of the virus from recent cases. According to GISAID, an international repository of viral genetic information, China submitted 15 sequences from two regions in the 17 days after lifting its “zero-covid” restrictions on December 7th. By January 9th it had provided 880, covering 11 of its 31 provinces (and province-level cities and regions). There was no evidence of any new variants.

Still, relative to the size of its population and its covid wave, the number of sequences China has submitted is small and insufficient to track the evolution of the virus, public-health experts say. Moreover, China is still not providing enough data on hospitalisations, intensive-care-unit (ICU) admissions and deaths to allow experts to assess quickly how the virus is behaving there and how dangerous any new mutations might be. Most absurdly, Chinese authorities reported only 37 covid deaths between December 7th and January 8th, the latest date for which official figures were available. Scientists’ models, satellite images of crematoriums and other independent sources suggest the real total is far higher—probably in the tens, if not hundreds, of thousands.

Even the WHO, usually reluctant to criticise China, has been damning. Dr Michael Ryan, who heads its Health Emergencies Programme, said last week that China’s figures “under-represent the true impact of the disease in terms of hospital admissions, in terms of ICU admissions, and particularly in terms of deaths”. He said the Chinese government’s definition of covid-related death was “too narrow”. China changed that definition in late December to include only deaths from covid-caused pneumonia or respiratory failure.

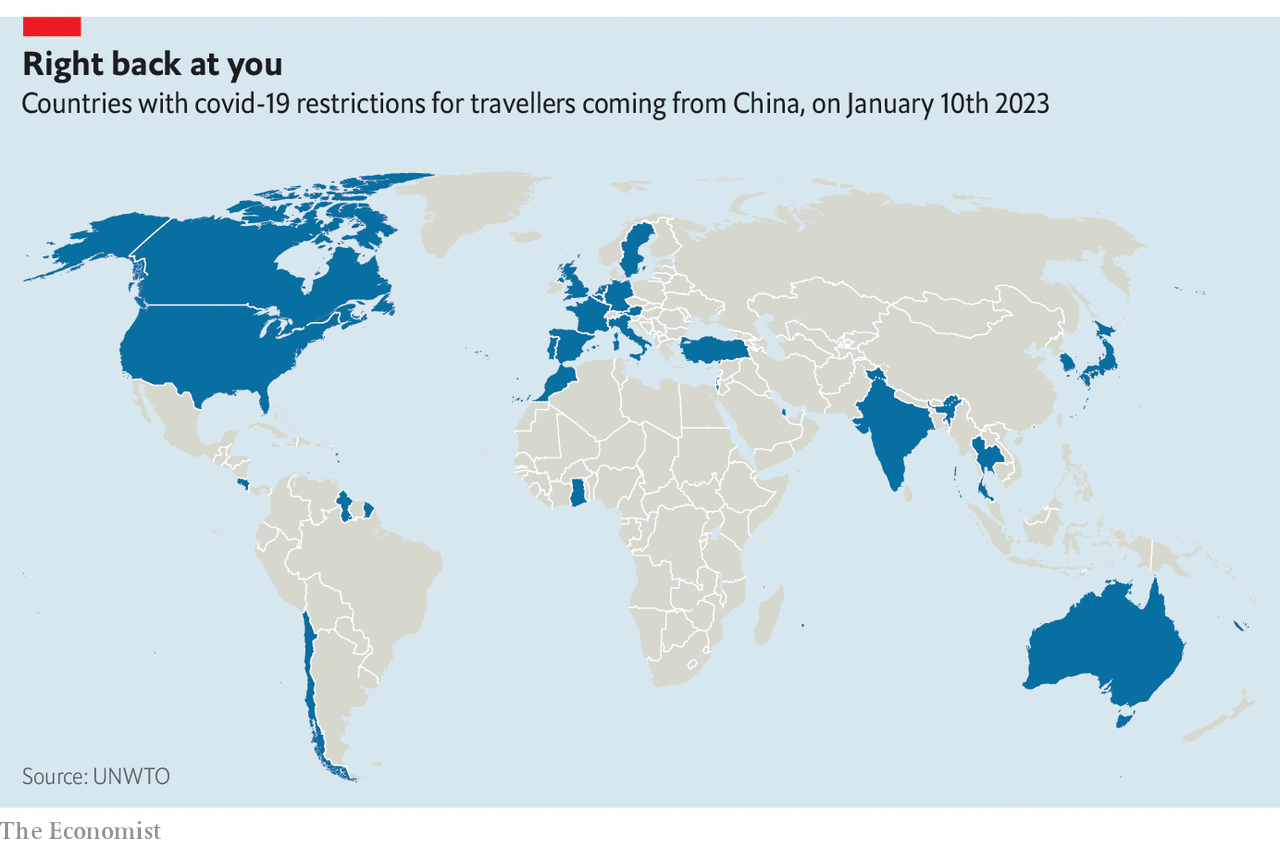

Several foreign governments have been critical, too, with at least 32 imposing restrictions on travellers from China as of January 10th, mostly requiring a negative covid test result (see map). With notable chutzpah, China has denounced such measures as politically motivated and threatened counter-measures—while maintaining its own demand that arrivals show a negative PCR test result. Tellingly, though, it is not just Western countries imposing such restrictions on China: India, Ghana, Qatar and Costa Rica have too. And while such measures may do little to contain the virus, the WHO says they are understandable given China’s lack of transparency.

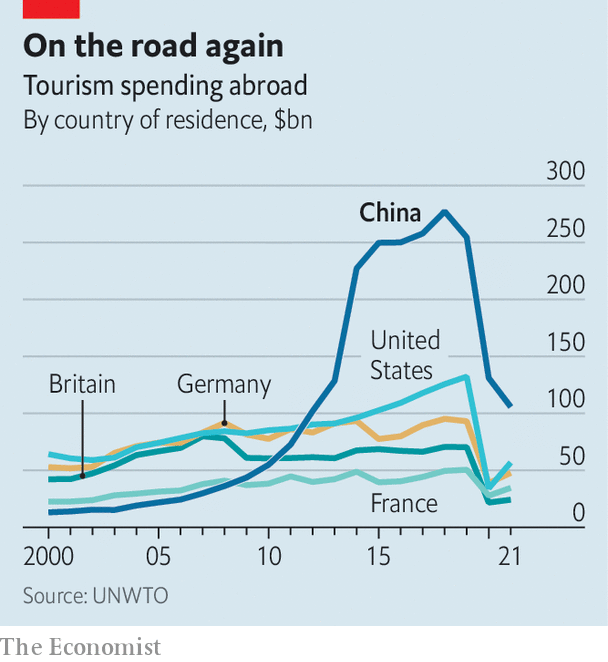

The row over travel restrictions may blow over soon, not least because many countries are desperate to welcome back Chinese tourists who, according to the UN’s tourism agency, spent some $255bn on foreign travel in 2019, almost 20% of the world’s total (see chart). But the spat could get uglier, especially if China—ever anxious to appease a nationalistic public—singles out America or European countries for new restrictions. On January 9th China’s foreign ministry voiced concern about the XBB.1.5 variant, which is sweeping across America, and urged authorities there to share more data and do more to stop it spreading.

More damagingly for China, though, its obfuscation of covid data is stirring memories in some countries of how it failed to share relevant information early in the pandemic (when it also denounced other countries’ travel restrictions) and how it is still withholding data that could help to trace the origins of the virus. Nor is it lost on many democratic governments that Mr Xi is motivated, in large part, by a desire to keep portraying his covid strategy as a success—and a demonstration of the superiority of his political model.

That could make it trickier for those who want America and its allies to take a less confrontational approach towards China. Few believe that Mr Xi’s recent shift in tone implies a substantial rethink of policy, especially on core issues like Taiwan. But it does suggest to many a willingness to moderate rhetoric, limit confrontation and perhaps seek progress in less sensitive areas, at least in the short term.

Ryan Hass of the Brookings Institution, a think-tank in Washington, suggests that Mr Xi may be emulating Mao Zedong’s strategy in the 1940s of “fight fight, talk talk”, buying time to regroup and study opponents. Nonetheless, Mr Hass is urging the Biden administration to seize the opportunity to make progress in areas of mutual concern, such as climate change and disease surveillance, as Mr Xi focuses on tackling covid and smoothing the ground for his expected attendance of an Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation summit in America in November.

But with an American presidential election looming in 2024, any such initiatives could be an even harder sell to America’s public, given the fresh controversy over covid data and travel restrictions. China hawks on both sides of Congress will no doubt be emboldened too, including Kevin McCarthy, the new Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives. He is already establishing a new China select committee that can conduct investigations, hold public hearings and make proposals on legislation. Another Republican-led committee is likely to pursue an investigation into covid’s origins this year.

European governments will probably be less overtly critical of China’s approach to covid, just as they were in early 2020. But that could quickly change if a new variant does emerge in China and spreads to Europe or if the Chinese government imposes new travel restrictions on European countries, says Noah Barkin, who studies China-Europe relations at Rhodium Group, a consultancy. “I would not under-estimate China’s ability to undermine its own rapprochement with Europe by over-reacting,” he said.

Nor will Mr Xi’s withholding of covid data help to reverse the recent deterioration of public attitudes to China in Europe, where many are upset by its failure to criticise Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That is already fuelling a fraught debate within the European Union over how to balance commercial interests against national security and democratic values in dealings with Mr Xi. Any new tension over covid could further complicate efforts to re-engage with China by Olaf Scholz, the German chancellor who visited Beijing in November, and by Emmanuel Macron, the French president who is due there early this year.

The potential fallout for China is much less severe in the Global South, especially among recipients of Chinese vaccines. At a briefing for foreign diplomats in Beijing on January 6th, ambassadors from Ecuador, Madagascar, Mongolia and Algeria praised China’s covid response. Mr Qin, the new Chinese foreign minister, is unlikely to hear much criticism from his hosts during his first trip abroad in the post, which started on January 9th and includes stops in Ethiopia, Gabon, Angola, Benin and Egypt.

The risk, though, is that in Mr Xi’s determination to preserve his public image, he will lose a rare opportunity to reset ties with the West and make real progress on issues of urgent global concern. Among the biggest casualties would be preparations for the next potential pandemic. China is essential to such efforts because of its vast population, wildlife trade and large numbers of coronavirus-bearing bats. But as the world learned in the SARS pandemic of 2002-03, and again over the past three years, transparency is also of vital importance. ■

The Economist