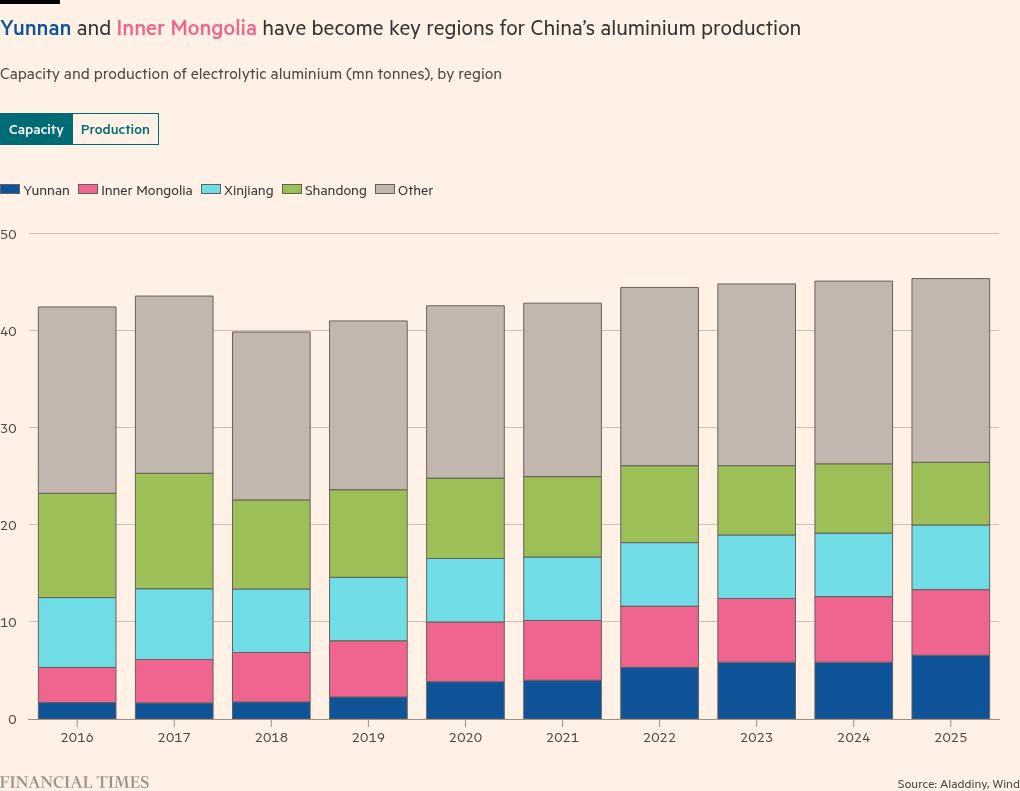

China’s aluminium industry has embarked on a green long march, moving millions of tonnes of production from the northern coal country, its stronghold for seven decades, to pockets of the south and west rich in renewable energy.

The country’s output of electrolytic aluminium, the sector’s main product, reached 43.8mn tonnes in 2024, accounting for about 60 per cent of the world’s total production, according to local industry data.

However, following a spree of relocations in recent years, 13mn tonnes of that capacity — about 30 per cent — now comes from new smelters in areas with clean energy and low-development costs in Yunnan, Sichuan, Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia.

The years-long multibillion-dollar relocation project is helping decarbonise one of the world’s dirtiest industries. Analysts believe the aluminium sector’s success will serve as a blueprint for Beijing to direct more aggressive production caps and capacity swapping in other industries.

“In China, there is always this trial system: you start from a city or province and, if it is successful, you ramp it up at a national level, and sectors are also the same,” said Isadora Wang, head of China at energy think-tank Transition Asia.

“The aluminium sector has been the most successful in implementing this capacity swap policy, but if it is proven to be useful, to be effective, then different sectors with some similarities will use it.”

Change has gathered pace since 2017, when China’s government set an annual domestic production cap of 45.5mn tonnes. The following year Beijing prohibited new smelting capacity in parts of the country already subject to strict air pollution prevention measures. And in 2020, President Xi Jinping set a goal for China to reach peak CO₂ emissions by 2030 and net zero emissions by 2060.

Taken together, these rules mean that companies building new smelters in the south and west also have to decommission an equivalent capacity in their traditional northern hubs, where they are dependent on coal-fired electricity.

Today, beneath clear skies in the south-western province of Yunnan, the future of an industry that has historically contributed to 5 per cent of China’s carbon emissions is coming into view.

Spanning several square kilometres, the industrial park in the small city of Wenshan houses new energy-hungry smelters producing alloys crucial for everything from ships and smartphones to electric vehicles and high-speed trains.

Nearby is a vast web of high-voltage lines delivering electricity from the region’s hydropower stations. The surrounding hills are either clad with solar panels or topped with wind turbines.

“China’s aluminium industry is undergoing a profound and systematic transformation,” Le Jiawen, Wenshan’s mayor, told local industry members at an event attended by the FT.

“Industrial competition is shifting from a battle of scale and cost to a comprehensive contest of ‘green’ and ‘low-carbon’ advantages.”

Plans have been drawn up for a new rail line to be constructed by about 2030, connecting the industrial zone to customers in China and neighbouring Vietnam and Laos, officials said.

China Hongqiao, the country’s biggest private-sector aluminium group by production volume, expects to finish its second smelter in Wenshan this year. When complete, its Yunnan operations will account for 4mn tonnes of annual capacity, just over 60 per cent of its total and equivalent to the US’s entire aluminium output.

Hongqiao, based in north-eastern Shandong, did not provide specific investment figures for the Yunnan relocation. However, according to company filings, the budget for its two new smelters was a combined Rmb45.6bn ($6.5bn).

A corporate presentation stated the relocation, paired with investments in solar and wind production in Shandong and Yunnan, would slash about two-thirds of the company’s carbon emissions.

Further impetus for the relocations has come from environmental policies in Brussels. The EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism means future imports of products such as steel, aluminium, cement and fertilisers face a carbon levy.

Within China, the relocation policy has raised questions about the viability of northern rust-belt regions, which risk being left behind by the green transition. Hongqiao said it would boost development and production of lower-volume, higher-value products in Shandong.

Environmentalists are also concerned that investments by some Chinese groups in Indonesia to secure bauxite-based materials — a key feedstock for aluminium in which China lacks supply — are underpinning coal-fired electricity growth in the south-east Asian nation.

Analysts from Dutch bank ING noted in December that China’s aluminium output was close to its self-imposed 45mn-tonne cap, keeping global prices high and prompting Chinese companies to expand capacity overseas.

US-based Human Rights Watch also highlighted in a 2024 report how an increasing proportion of aluminium being produced in Xinjiang raised the risk of multinational companies’ supply chains being implicated in Beijing’s long-running campaign of repression in the region.

The decarbonisation strategy has sparked aggressive competition between China’s cash-strapped local governments, each aggressively vying for investments.

Official promotional material from Inner Mongolia and Yunnan, reviewed by the FT, shows governments offering policy support including tax breaks, research and development subsidies, and cheap electricity, water, gas and land.

The low power prices in particular are an “important consideration” for companies as they choose new locations, said Shen Xinyi, who leads the China team for the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, a European think-tank.

In a presentation to industry members in December, Fan Shunke, deputy secretary of the Communist Party committee for the China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association, said the relocation strategy and production caps meant emissions from China’s aluminium industry had peaked in 2024.

He touted that China now boasted the world’s only “complete” aluminium ecosystem, pointing to more than 20 industry clusters nationwide that included not only smelters but also facilities for producing bauxite and prebaked carbon anodes.

“The US does not have this, Europe is even less capable and the Middle East wants to build one,” said Fan.

Additional contributions by Wenjie Ding in Wenshan