In 2015, China welcomed almost 16.5mn babies. A decade later, that figure has more than halved to just under 8mn — a striking example of a demographic crisis that is poised to have long-term economic and societal consequences in the world’s second-largest economy.

While China is not alone in grappling with an ageing population, particularly in east Asia, the pace of ageing has been accelerated by the legacy of the “one-child” policy, a weak economy and a growing divide between young men and women’s prospects and intentions.

The “shockingly low number” of new births meant that the “total population will shrink much faster and will become more dominated by the elderly than even in recent pessimistic forecasts”, said Ernan Cui, an expert in Chinese demographics at the consultancy Gavekal Research.

A UN prediction that China’s population would shrink from 1.4bn people in 2024 to 1.3bn by 2050, hitting 633mn by 2100, would probably have to be “sharply revised” to reflect the more “rapid deterioration in fertility”, she said.

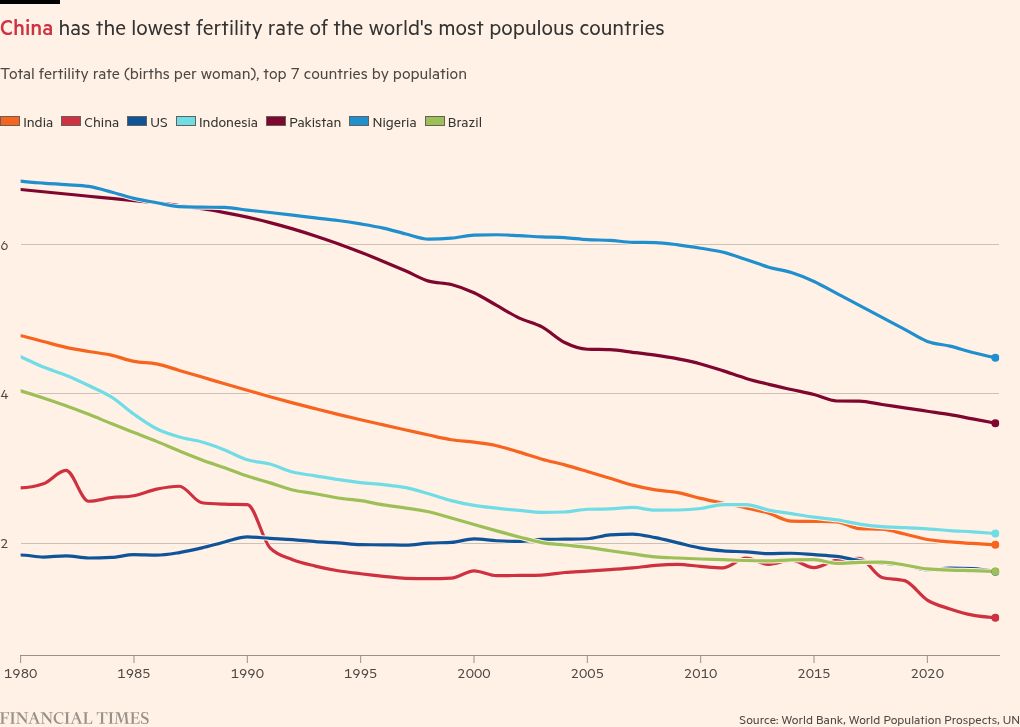

“With this new record-low number of births, China has become the lowest-fertility society among the most populous countries,” said Wang Feng, an expert in China’s demographics at the University of California, Irvine.

China’s fertility rate, a measure of how many children a woman has in her childbearing years, is just 0.98, far below the 2.1 needed to keep the population stable.

At the root of the baby bust is the fact that fewer people are getting married.

China’s past birth control policies have resulted in a smaller cohort of young people entering marriage age. The “one-child” policy implemented in 1980 restricted most couples to a single child until 2016 and limits on family sizes were scrapped only in 2021.

More people are also deciding against or delaying marriage. About 30 per cent of 30-year-olds were unmarried in 2023, compared with 14.5 per cent in 2013, according to official data.

“The recent decline in births is not driven by couples who end up having fewer children but fewer people becoming couples in the first place, or by forming couples later in life when it is more difficult to have children,” said Cui.

The economy was the “fundamental force” that was driving young people to “delay or forgo marriage”, said Wang. While China’s export industries are wowing the world with cheap and advanced AI and electric vehicles, its domestic economy is weak, leaving fresh graduates facing the toughest job market in modern times.

“China has yet to fully recover from the devastating zero-Covid control campaigns, during which many small businesses in the informal sector — the sector that employs the majority of the country’s young labour force — were forced to shut down,” Wang said.

China’s official urban youth unemployment rate for ages 16 to 24 ranged between 14.5 per cent and 18.9 per cent last year, fluctuating with seasonal demand for temporary workers, and experts believe the real numbers are much higher.

The precarity wrought by the weak jobs market had been compounded by “an urban housing crisis that has erased a substantial share of hard-earned household wealth” that had “fuelled rising pessimism among China’s young people”, added Wang.

Ma, a 35-year-old video producer from Guangdong, who declined to give her first name, was clear in her pessimism about the economy.

“My friends don’t want to spend the little money they have on another person. If they do have a lot of love to give, they’re much more likely to share it with a pet,” she said.

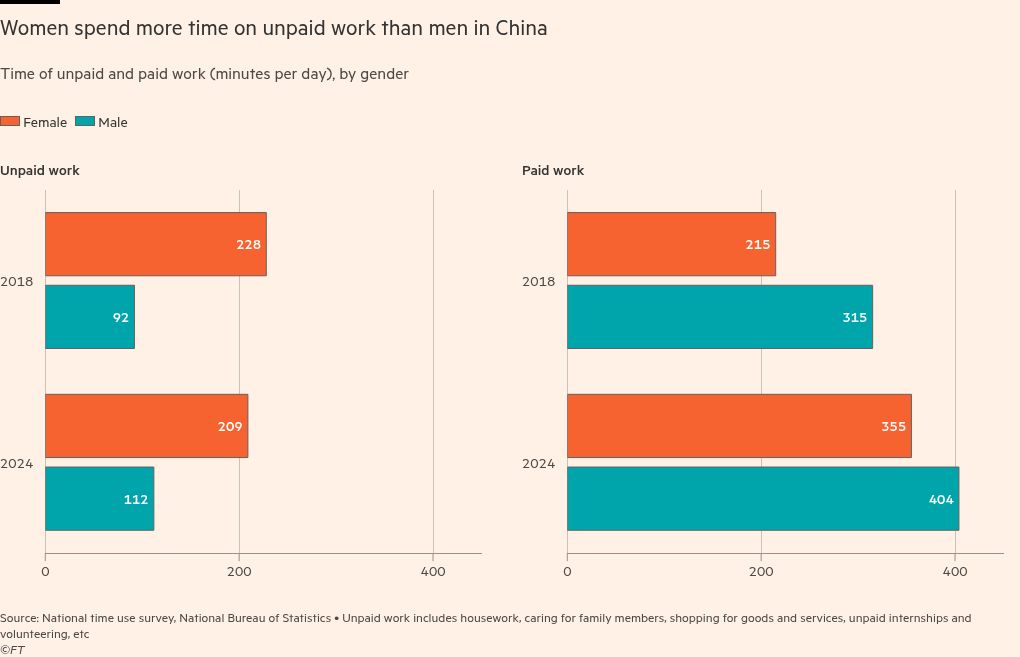

China, like other east Asian countries, has highly gendered norms about women’s responsibilities in the household. Women on average spend 87 per cent more time on unpaid work such as cleaning and caregiving than men, according to an official survey. This equates to 209 minutes on average per day.

“There is a very strong social assumption that women are the ones who end up doing most of the caregiving, and that having children will affect a woman’s job and career path,” said Ma.

At the same time, the average Chinese woman is often far more educated than her male peer.

Since 2009, women have outnumbered men in undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at Chinese universities. This has created an urban-rural gender divide, where women migrate to cities to find work, as men remain in their hometown villages.

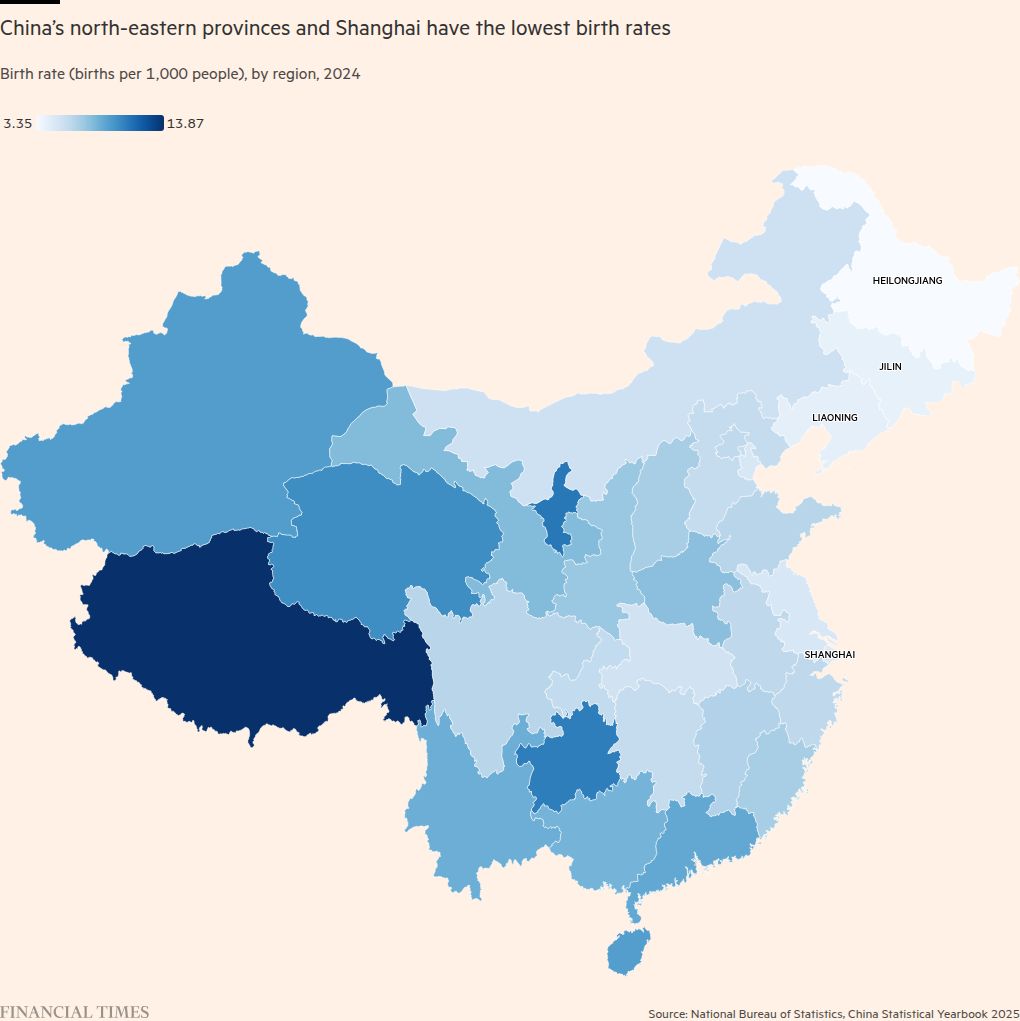

As a result, the birth rate is lowest in male-dominated agricultural and industrial provinces such as Liaoning and Heilongjiang.

Meanwhile, Shanghai has the fourth-lowest birth rate — the number of live births per 1,000 individuals — among Chinese provinces, a reflection of the higher concentration of well-educated women that creates a gender imbalance in dating.

Men outnumber women on average across the country in part due to the common practice of sex-selective abortions during the one-child policy era.

Meanwhile, it is common for young men to complain that women are overly materialistic in searching for a partner, a belief reinforced by social media portrayals of ideal relationships where the boyfriend lavishes his partner with expensive gifts.

“I’m tired of going on dates with women who expect their partners to buy her designer handbags, pay for expensive meals and not take any responsibility,” said a 30-something tech worker surnamed Zhang in Beijing. His complaints are widely echoed on social media and in popular TV shows, with warnings against men marrying “gold-diggers”.

The rising number of people divorcing also serves as a cautionary tale for many, particularly young women. In 2013, about 2.6 per cent of people aged 40 were divorced. A decade later, the figure was 5 per cent.

While rising divorce rates are associated with greater female independence as women have the financial security to seek separation, female divorcees are still stigmatised and single mothers often find it difficult to date.

Beijing has introduced a swath of measures to encourage young people to get married and have children, from subsidies for newborns to extended vacation leave for honeymooning civil servants and relaxed rules on marriage registration.

So far these policies have had limited impact, with Cui noting that it was harder to devise policy to encourage young people to tie the knot than support for married couples to have more children.

The baby bust adds to the economic challenges facing China, already struggling with deflation, a weak property market and subdued consumption. Some see echoes of Japan and warn of the longer-term impact on the economy.

“In Japan, the expectation of an ageing demographic weighed on long-term growth expectations among businesses and households,” said Goldman Sachs chief China economist Hui Shan.

“It created a negative feedback loop where companies and households reined in investment and spending in expectation of lower growth. The debt overhang from the asset bubble amplified this effect.”

Some are adjusting to a new reality.

Ma said her neighbours once hassled her about plans for marriage and family, but “now, they don’t ask any more”. They stopped after a young mother in the apartment block developed post-partum depression. “There are stories like that everywhere now,” she said.

For others, the path ahead appears fraught. Zhao Wenjing, a PhD student in Beijing in her late twenties, said it was not “easy to find a reliable man”.

“Social change is happening too fast, and it’s very hard to find a suitable partner who shares the same values. Without that, it’s even harder to move on to the next step,” she said.