Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

History rhymes. Over the past week, we’ve seen many analogies drawn between the Monroe Doctrine and President Donald Trump’s new imperialism — and rightly so, given that the administration itself is making them (just read the recent national security strategy).

But what’s happening in Venezuela today, and what may yet happen in Greenland, or in Ukraine or Taiwan (where Russia and China could well take counteraction as a response to what the White House is doing), isn’t only about the protection of America’s backyard, as in the Monroe Doctrine. It is about a messier and much more global conflict.

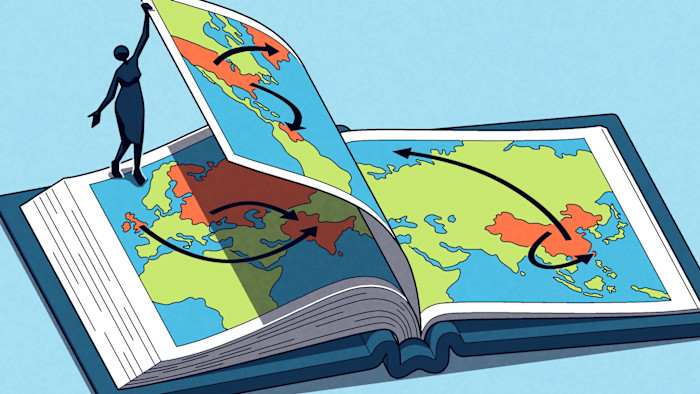

For this reason, the historical comparison I’ve been thinking about lately is the “great game” between Russia and Britain in the 19th century. That conflict roped in adversaries and allies alike, many of whom changed sides multiple times during a decades-long struggle for supremacy in Central Asia. This time around, it is the US and China that are locked in a new great game. There are three areas where we can see especially strong similarities between power struggles two centuries ago and those of today: mining, mapping and mercantilism.

Start with the hunt for natural resources. In the 19th century, the pot of gold was India and Central Asia, rich with spices, precious metals and opium. Today, the competition is taking place in Latin America and the Arctic, and is all about fossil fuels and rare earth minerals.

Venezuela and Greenland each have both, along with strategic ports. Just as Chinese energy and infrastructure build-up in Latin America was one reason for Trump’s Venezuela action, so both countries are jockeying for resources in the High North. There’s already a Chinese state-owned firm investing in the Kvanefjeld mineral field in Greenland. Beijing has also increased diplomacy in the country over recent years.

It’s not just minerals that the US wants; it desires a China-free Arctic. The Chinese, often via Russian proxies, have become much more present in the Arctic Circle region, where there are not only big untapped fossil fuel deposits but other prizes like fisheries, new shipping corridors, and the ability to use them to lay underwater fibre optic cables.

To exploit these resources and strategic aims, both countries are mapping the area in more detail, often using sonar technology, which is much more accurate than satellite. This is a direct echo of the original great game. Back then, the British conducted emergency mapping missions between Russia and India to understand which way the adversary might come. As Peter Hopkirk lays out in his book The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia, mapping and espionage were one and the same.

The same is true today for countries that want to claim natural resources and conduct cyber-espionage. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea says that a country’s economic zones can extend 200 nautical miles out from the continental shelf. So tracking exactly where those shelves are becomes quite important. The US and Russia are both doing that today, while China even ran its own submarines under Arctic ice this past summer, presumably for purposes both economic and defensive.

The idea then and now is to get ahead of the battle, rather than to engage directly. Beat a rival to a given territory and then be the first to exploit resources and alliances. This “forward” strategy avoids outright war, but leads to all sorts of intrigues, minor battles, shadow conflicts, deals with buffer states, and differences of opinions about borders.

Then, like now, countries could be “frenemies” amid the power struggle. In the 19th century, Russia and France fought together and against each other at different times. The Afghans and Persians frequently changed their allegiances. Today, China and Russia are partners in the Arctic. China, Russia, Iran and North Korea also represent a kind of anti-American axis. But the alliances are fragile, as are America’s relationships with allies such as Canada and Finland, which are meant to be partners in a new shipbuilding industrial strategy.

The complexity will only grow. European countries are split not just on the ousting of Nicolás Maduro but also on what to do should Greenland be annexed. I suspect that Trump’s senior adviser Stephen Miller is right when he points out that nobody is going to fight for Greenland. Recent polls showed only 38 per cent of German citizens and 16 per cent of Italians of fighting age would pick up arms to defend their own country.

That said, the mercantilism driving both China and the US will, by its very nature, involve conflict and collaboration with multiple nations, as the primary actors circle each other warily, looking to expand their influence without engaging in a hot war. The original great game played out indirectly through proxy conflicts. This will be the case today. Europe, Korea, Japan, Australia, part of Africa and Latin America all have skin in this game. They must make non-binary choices between the US and China, and it will take decades for things to settle.

As Hopkirk writes: “Some would maintain that the great game never really ceased, and that it was merely the forerunner of the cold war of our own times, fuelled by the same fears, suspicions and misunderstandings.” All those things are in evidence today. The past is, after all, never really past.