Donald Trump’s intervention in Venezuela has sent shivers down the spine of oil buyers in China, not only because of their reliance on Venezuelan crude but because it highlighted Washington’s ability to interfere with larger suppliers, such as Iran.

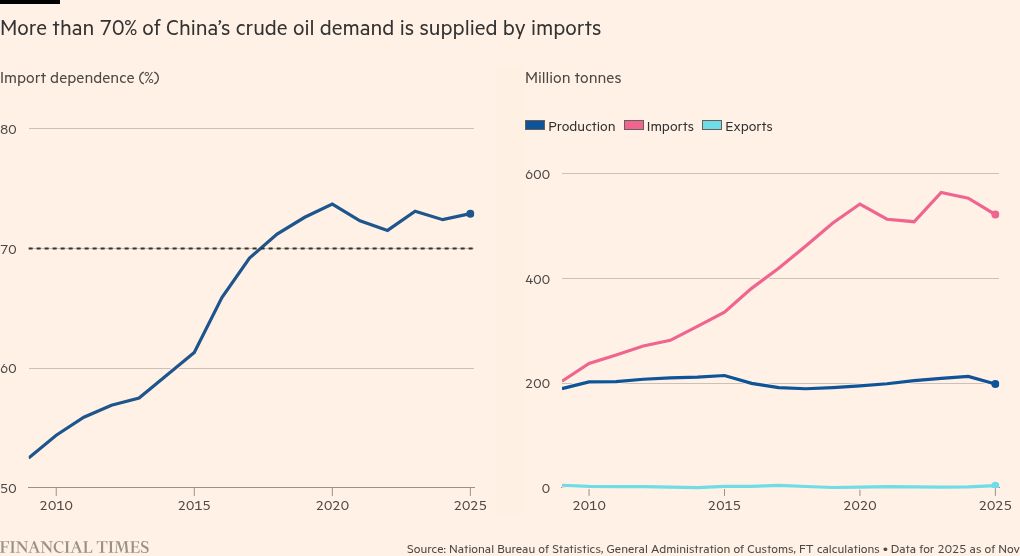

China is one of the world’s biggest importers of crude oil, and about 20 per cent of its purchases comes from suppliers subject to sanctions by the US and west.

If the US were to follow its attack on Venezuela with action against Iran, it would further cut into China’s supply of cheap oil under sanctions, potentially hitting its economy and giving Washington a point of leverage over Beijing.

Chinese refiners “are generally expecting something is going to happen in the Middle East”, said Muyu Xu, senior research analyst for crude at data provider Kpler, adding this would force them to consider higher cost, alternative supply sources.

She said this would bring disruption to China’s refining sector if the intervention stopped the flow of cheap oil from Iran, because “the volumes from there are much, much bigger than Venezuela”.

While China’s demand for oil is decelerating as it transitions to electric vehicles and amid a years-long slump in the property sector, it remains the world’s second-biggest overall consumer of crude.

Beijing has hit out at the US intervention, accusing Washington of “bullying” Caracas and saying demands for oil “infringe upon Venezuela’s sovereignty, and harm the rights of the Venezuelan people”.

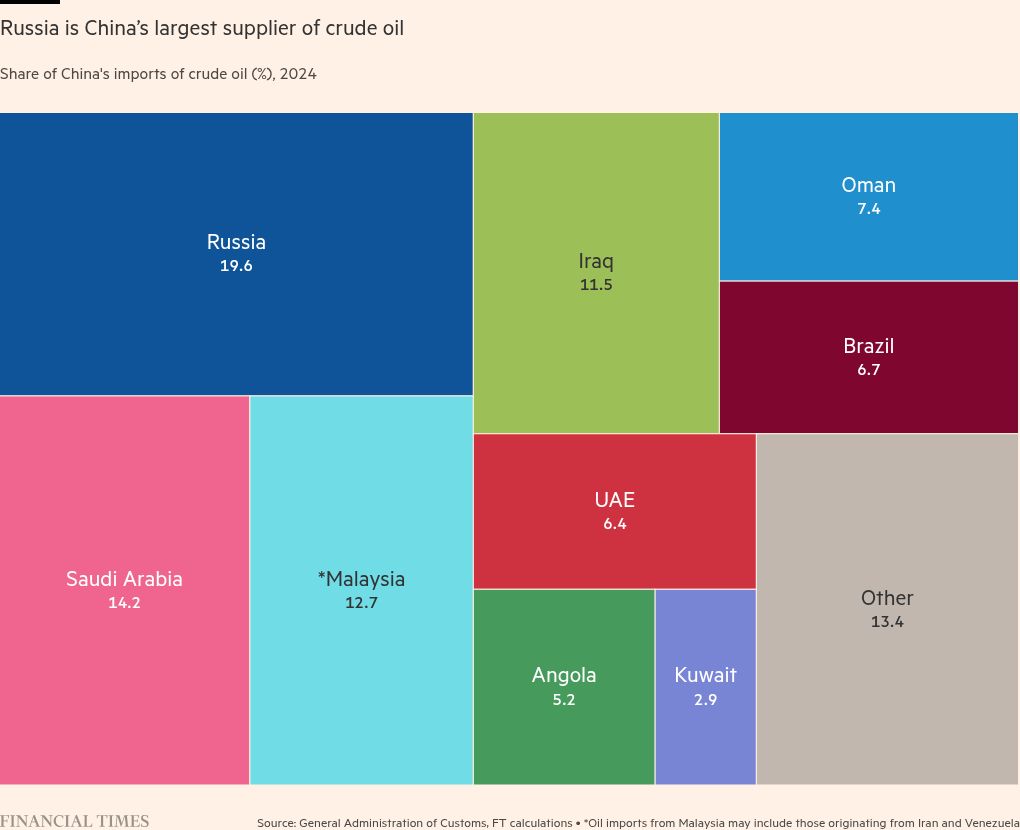

Russia is China’s biggest crude supplier, accounting for 20 per cent of imports, according to Chinese customs data, followed by Saudi Arabia at 14 per cent and 13 per cent from Malaysia, through which analysts believe sanctioned Iranian and Venezuelan oil is smuggled.

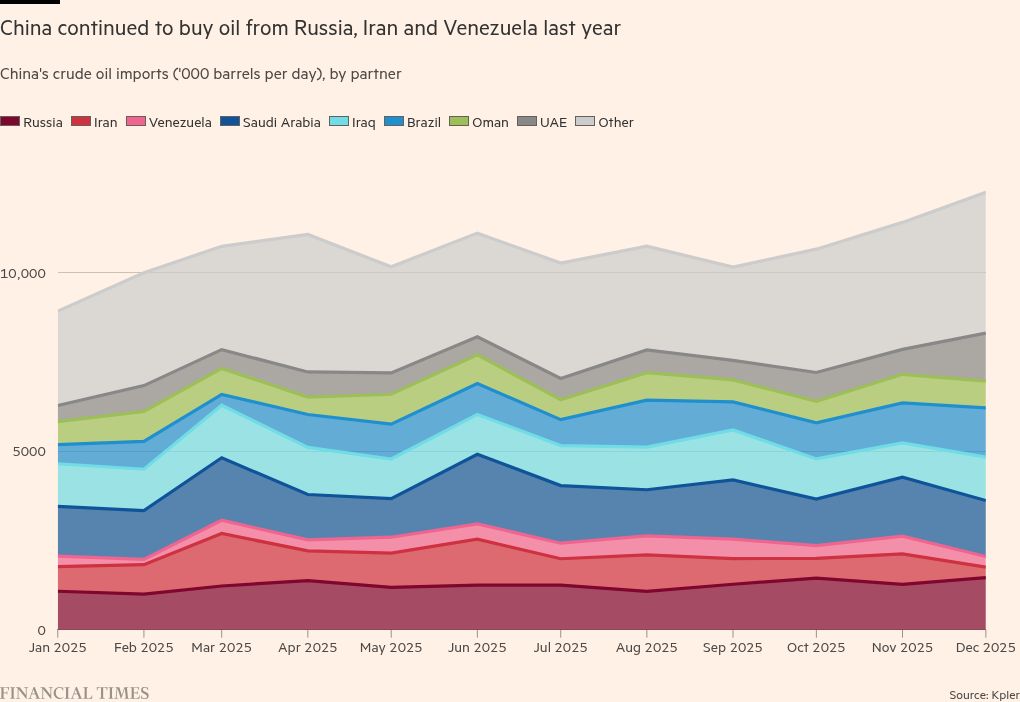

China has also been Venezuela’s biggest buyer since 2020, when the US tightened sanctions on the South American country. Venezuela’s crude exports to China averaged about 395,000 barrels a day in 2025, accounting for nearly 4 per cent of China’s seaborne crude imports, according to Kpler data.

Much of the sanctioned oil supply is “transhipped” — a process by which tankers from “shadow fleets” clandestinely transfer oil to intermediary vessels — in waters near Malaysia to disguise its origin.

Malaysian oil exports to China increased from 5,400 barrels per day in 2015 to 1.4mn bpd in 2024, far exceeding domestic production, said Erica Downs, a senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy in Columbia University, in testimony to the US Congress last year. She added that crude oil subject to US and other western sanctions amounted to about one-fifth of China’s total imports in 2024.

Even if Venezuelan oil continues to flow to China, the US intervention was a “meaningful geopolitical development” for Beijing because the US will exert “influence over the industry”, said Richard Bronze, head of geopolitics at consultancy Energy Aspects.

The US said on Wednesday it will seek to control Venezuelan oil sales “indefinitely”, funnelling the proceeds to American companies and open the country to US oil services groups.

Chinese state-owned refiners such as PetroChina had largely stopped buying Venezuelan oil in the wake of the US sanctions, even though Caracas’s state oil company PDVSA still owes China shipments under loans-for-oil agreements.

But independent refiners, known as “teapots”, have continued to take Venezuelan oil supply, as well as sanctioned crude from Iran and Russia. These operators account for about a quarter of China’s total crude processing capacity.

This has made them highly exposed to the risk of US intervention, analysts said.

In five years, China’s imports of Iranian crude have surged nearly threefold to 1.4mn bpd, accounting for more than 13 per cent of the country’s total seaborne shipments.

Any cessation of Iranian oil flows would be “a concern for all importers and China is the biggest crude importer out there”, Bronze said.

The loss of discounted Iranian oil would force China’s teapot refiners to pivot to more expensive sources such as Saudi Arabia, Brazil or West Africa. Increased costs would create upheaval in the industry as refiners began to take losses, said Kpler’s Xu.

“That’s really the worst-case scenario — nobody really wants to start thinking of that because if that happens that would mean a lot of the teapots probably would need to shut down.”

Bronze noted that China had been steadily building a buffer of reserves to ensure against geopolitical disruption. He said that China’s dominant market position — as well as an oversupply of crude this year that has put downward pressure on prices — would also offer Beijing a degree of protection from geopolitical disruption.

According to Downs, China’s above- and below-ground strategic and commercial storage facilities could hold enough crude to cover 183 days’ worth of imports at 2024 levels.

China “has pipeline routes, seaborne imports, is Russia’s biggest customer and, for most of the Middle Eastern exporters, China is their priority”, said Bronze. “China is probably going to be at the front of the purchasing queue for a lot of suppliers.”

Still some analysts expressed doubts about Trump’s appetite for taking decisive action against the Iranian regime. Prior to his abduction by US forces at the weekend, Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro was presiding over an economy in freefall.

“In Venezuela, it’s like a building that’s already rotten — when it’s about to collapse, just give it a push. The cost is very low,” said Cui Shoujun, professor with the School of International Studies and associate dean of the School of Global Governance at Renmin University of China.

“If Iran ever reaches the brink of collapse one day, the US and Israel might give it a shove too, but before it hits that critical point, the US won’t rashly intervene,” he said.

With additional contributions from Cheng Leng, Tina Hu and Wenjie Ding in Beijing. Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong