The mission demanded the utmost secrecy.

A team of American climbers, handpicked by the C.I.A. for their mountaineering skills — and their willingness to keep their mouths shut — were fighting their way up one of the highest mountains in the Himalayas.

Step by step, they trudged up the razor-toothed ridge, the wind slamming their faces, their crampons clinging precariously to the ice. One misplaced foot, one careless slip, and it was a 2,000-foot drop, straight down.

Just below the peak, the Americans and their Indian comrades got everything ready: the antenna, the cables and, most crucially, the SNAP-19C, a portable generator designed in a top-secret lab and powered by radioactive fuel, similar to the ones used for deep sea and outer space exploration.

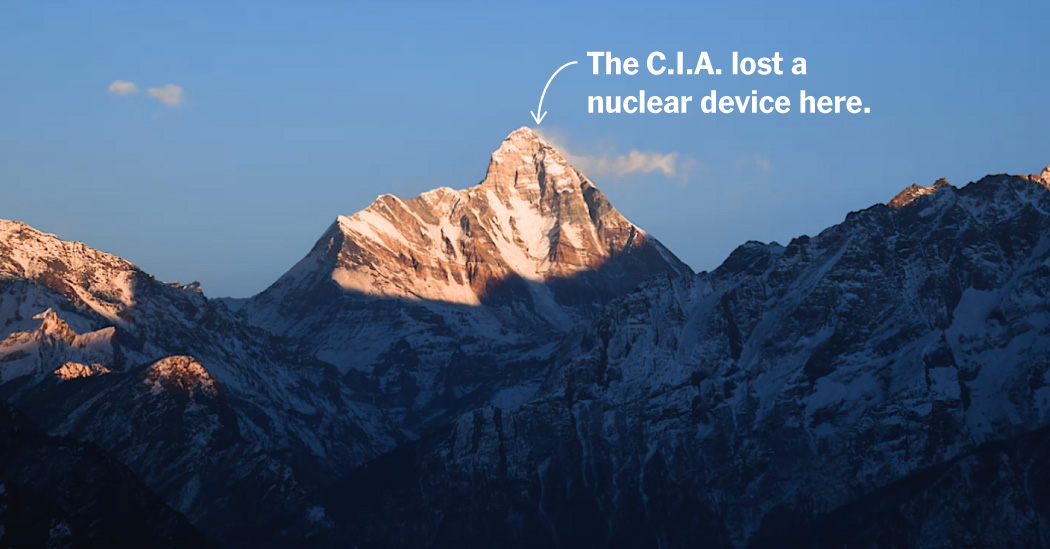

The plan was to spy on China, which had just detonated an atomic bomb. Stunned, the C.I.A. dispatched the climbers to set up all this gear — including the 50-pound, beach-ball-size nuclear device — on the roof of the world to eavesdrop on Chinese mission control.

But right as the climbers were about to push for the summit, the weather went haywire. The wind howled, the clouds descended, a blizzard swept in and the top of the forbidding mountain, called Nanda Devi, suddenly disappeared in a whiteout.

From his perch at advance base camp, Capt. M.S. Kohli, the highest-ranking Indian on the mission, watched in panic.

“Camp Four, this is Advance Base. Can you hear me?” he recalled shouting into a walkie-talkie.

No response.

“Camp Four, are you there?”

Finally, the radio crackled to life with a faint voice, a whisper through the wash of static.

“Yes … this … is … Camp … Four.”

“Come back quickly,” Captain Kohli remembered ordering them. “Don’t waste a single minute.”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

Then Captain Kohli made a fateful decision. He needed to, he said — to save the climbers’ lives.

“Secure the equipment. Don’t bring it down.”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

The climbers scampered down the mountain after stashing the C.I.A. gear on a ledge of ice, abandoning a nuclear device that contained nearly a third of the total amount of plutonium used in the Nagasaki bomb.

It hasn’t been seen since.

And that was 1965.

Capt. M.S. Kohli with fellow Indian mountaineers at the 1965 World’s Fair in New York.

Captain Kohli’s archive

Buried beneath the rock and ice of the Himalayas, in one of the most remote places on earth, lies a sensational chapter of the Cold War, and it’s not over yet.

What happened to the American nuclear device, which contains Pu-239, an isotope used in the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, and even larger amounts of Pu-238, a highly radioactive fuel?

Nobody knows.

After losing it at the top of that mountain 60 years ago, the American government still refuses to acknowledge that anything ever happened.

The whole mission was wrapped in deception from the very beginning. A trove of files just discovered in a garage in Montana show how a celebrated National Geographic photographer built an elaborate cover story for the covert operation — and how the plans completely unraveled on the mountain.

Extensive interviews with the people who carried out the mission and once-secret documents stashed away in American and Indian government archives reveal the extent of the debacle, and the ways American officials at the highest levels, including President Jimmy Carter, tried to cover it up years later.

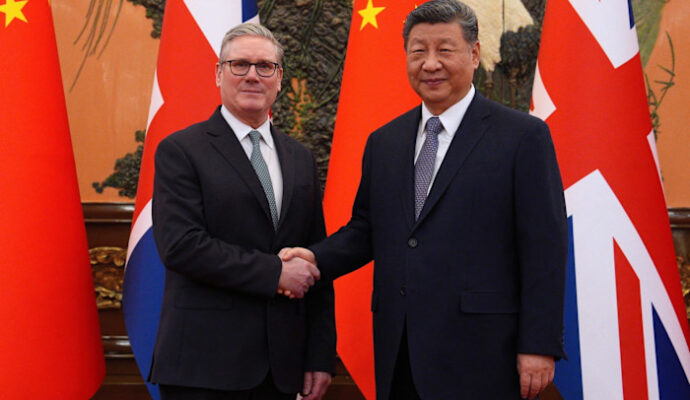

The documents trace the anxiety spreading in Washington and New Delhi. Back then, just as now, the United States and India had a tricky relationship. They were both worried about China’s growing nuclear capabilities. They were both watching the Soviet Union’s designs on Afghanistan. They both had a precarious Cold War chessboard to manage. And just like today, the two nations, as the world’s two largest democracies, had reasons to partner up but didn’t trust each other.

The lost nuclear device and the dangers it posed could have easily led to a breakdown between them. But the files show Mr. Carter and Morarji Desai, the Indian prime minister at the time, overcoming their mutual suspicions and working together in secret, hoping to make the problem go away.

Only, it didn’t.

The first wave of the scandal broke in the 1970s, and even now, decades later, people in India are demanding answers. Villagers in remote settlements high up in the Himalayas, environmentalists and politicians worry that the nuclear device could slide into an icy stream and dump radioactive material into the headwaters of the Ganges, India’s most sacred river and a lifeline to hundreds of millions.

The banks of the Ganges in Varanasi, India. Some fear the missing device could spread radiation into the river system, which supports hundreds of millions of people.

It’s unclear how hazardous that would be. There’s so much water roaring through these mountain gorges that the sheer volume could dilute any contamination.

But plutonium is highly toxic, with the potential to cause cancer in the liver, lungs and bones. As the glaciers melt, the generator could emerge from the Himalayan ice and sicken anyone who stumbles upon it, especially if it’s damaged.

Scientists say the generator will not explode on its own — for one, there’s no trigger, unlike in a nuclear weapon. But they worry about a sinister scenario in which the plutonium core is found and used for a dirty bomb.

Note: This illustration is based on New York Times interviews with experts familiar with the device and on reference drawings of similar SNAP devices from NASA and Martin Marietta Corporation documents.

Just this past summer, a prominent Indian lawmaker brought up the missing device again, warning on social media that it was potentially dangerous and later saying in an interview: “Why should the people of India pay the price?”

The men who carried the device up the mountain and took an oath of silence decades ago have lived with a gnawing fear ever since they lost it. Many were reaching the end of their lives when The New York Times tracked them down and interviewed them. Some, including Captain Kohli, have recently died.

“I’ll never forget the moment Kohli left it up there,” said Jim McCarthy, the last surviving American climber on the mission. “I had this flash of intuition we’d lose it.”

“I told him, ‘You’re making a huge mistake,’” he recalled. “‘This is going to go very badly. You have to bring that generator down.’”

Jim McCarthy, the last surviving American climber, who said he had a premonition about losing the nuclear device, at his Colorado home in 2022.

Stephen Speranza for The New York Times

Six decades later, at age 92, Mr. McCarthy could barely control the emotion in his voice as he recounted what happened.

“You can’t leave plutonium by a glacier feeding into the Ganges!” he shouted from his living room in Ridgway, Colo. “Do you know how many people depend on the Ganges?”

‘Are You Out of Your Mind?’

Before solar technology took off, NASA considered these kinds of generators well suited to keep unattended machines running in the extreme conditions of space.

They work by converting heat from radioactive material into electricity, and NASA credits them with enabling “some of the most challenging and exciting space missions in history.”

Voyager I, the interstellar probe launched more than 45 years ago that is still drifting through the cosmos, some 15 billion miles away, continues to communicate with Earth thanks to these generators. They were developed in the 1950s for the first generation of satellites.

But by the mid-1960s, they entered a new realm: espionage.

In October 1964, China detonated its first atomic bomb. It was a 22-kiloton explosion (bigger than the Nagasaki bomb) in the Xinjiang region, far beyond the Himalayas.

President Lyndon B. Johnson had been so fixated on blocking China from going nuclear that some of his advisers had considered covert strikes. But now, China had beaten him to the punch.

Keeping tabs on China’s nuclear evolution was especially hard because neither the United States nor India had much human intelligence inside the country.

That’s why, according to several people involved, an outlandish plan began to unfold during, of all things, a cocktail party.

Gen. Curtis LeMay was the head of the United States Air Force, a Cold War hawk and one of the architects of America’s nuclear weapons strategy, long remembered for his threat to bomb North Vietnam “back into the Stone Ages.”

Major General Curtis E. LeMay, a key figure in the U.S. Airforce, was the one who envisioned the secret mission to Nanda Devi.

Getty Images

He was also a trustee at the National Geographic Society. At the party, he was having drinks with Barry Bishop, a photographer for the magazine and an acclaimed mountaineer who had summited Mount Everest.

Over cocktails, Mr. Bishop regaled General LeMay with tales of the dreamy views from the top of Everest and of being able to see for hundreds of miles across the Himalayas deep into Tibet and inner China.

The conversation apparently got the general thinking.

Soon after the party, the C.I.A. summoned Mr. Bishop, according to conversations that Mr. Bishop shared with Captain Kohli and Mr. McCarthy (Mr. Bishop and General LeMay died in the 1990s).

The C.I.A. laid out a bold plan. A group of American alpinists working for the agency would slip into the Himalayas undetected, drag several backpacks stuffed with surveillance equipment up the slopes and install a secret sensor at the top of a mountain to intercept radio signals from Chinese missile tests.

Mr. Bishop was a logical choice for their secret ringleader. He was a military veteran and a tested climber with an excellent cover. As a National Geographic photographer, he often disappeared for months at a time to far-flung corners of the earth.

Records found in November in Mr. Bishop’s garage in Bozeman, Mont., show that National Geographic granted him a leave of absence to pursue the mission in the Himalayas. The meticulously kept files also chronicle his deepening involvement: studying explosives, receiving intelligence on China’s missile program and mapping out the summit assault. His files included bank statements, phony business cards, photographs, gear lists and menus, down to the chocolate, honey and bacon bars that the climbers would eat.

The mission’s success hinged on two breakthroughs for the spy world: the portable nuclear devices and missile telemetry. By the early 1960s, scientists working for America’s most secret labs had figured out how to catch radio signals from ballistic missiles flying high in the sky.

Naturally, their biggest concern was the Soviet Union, which the spy services had ringed with telemetry stations from Alaska to Iran, according to National Security Agency documents declassified in the past few years. The tactic was working, so the C.I.A. tried to copy and paste the same approach for China.

By putting an unmanned station on top of the Himalayas, the C.I.A. hoped to pluck radio signals from high-altitude missiles launched from China’s Lop Nur testing grounds, nearly a thousand miles away in Xinjiang.

The whole operation rested on keeping the mountaintop equipment running — for a long, long time. And that’s where the portable generator powered by highly radioactive plutonium came into play.

Mr. Bishop couldn’t rig up the equipment himself. Frostbite from Everest had claimed his toes and he couldn’t handle technical climbs anymore. So the agency tasked him with recruiting the best, most trustworthy alpinists he could find. He started with Mr. McCarthy, a spidery rock climber who graced the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1958 hanging off a cliff.

Barry Bishop after conquering Mount Everest in 1963, sitting with his wife, Lila. Mr. Bishop played a key role in covertly organizing the Nanda Devi mission.

Associated Press

Mr. McCarthy said the C.I.A. offered him $1,000 a month and presented the mission as urgent for America’s national security. He was a young lawyer and felt a patriotic pull to participate, he said. (The details he provided have been corroborated by Mr. Bishop’s files, interviews with others involved in the mission, photo records and formerly classified documents from the National Security Agency, the Atomic Energy Commission, the State Department and Indian government archives).

The C.I.A. then turned to India for help.

“Maybe two or three people in the entire government knew about this,” explained R.K. Yadav, a former Indian intelligence officer.

The circle may have been small, Mr. Yadav said, but the Indian government’s fear of China going nuclear was intense.

“You see, we had just lost a war to China — no, not just lost, we had been humiliated,” Mr. Yadav said, referring to the brief but intense flare-up along China and India’s border in 1962.

India’s Intelligence Bureau tapped Captain Kohli, a decorated naval officer who had been scaling mountains since he was 7, to head up the Indian side of the mission. Captain Kohli had just made history leading nine Indian climbers to Everest’s summit.

He was immediately struck by the C.I.A.’s arrogance.

“It was nonsense,” Captain Kohli said during extensive interviews with The Times over the past few years. He died in June.

The first plan that the C.I.A. hatched, he recalled, was to put the telemetry station on Kanchenjunga, the world’s third-highest mountain after Everest and K2.

“I told them whoever is advising the C.I.A. is a stupid man,” Captain Kohli said.

Captain M.S. Kohli at his residence in Nagpur, in Maharashtra, India, in 2023.

Mr. McCarthy had the same reaction.

“I looked at that Kanchenjunga plan and said, ‘Are you out of your mind?’” he remembered.

“At that time, Kanchenjunga had only been climbed once,” Mr. McCarthy said. “I told them, ‘You’re never going to get all that equipment up there.’”

Mr. Bishop waved off the concerns.

He made business cards, letterhead and a prospectus, all emblazoned with “Sikkim Scientific Expedition” (named for a kingdom in the Himalayas). He called himself “chairman and leader.”

He announced that the climbers were going up into the mountains to study atmospheric physics and physiological changes at high altitudes. To make it look even more legit, he gathered letters of support from the American Alpine Club, National Geographic and even an assistant to Sargent Shriver, the Peace Corps director and President John F. Kennedy’s brother-in-law.

Letters of support for Mr. Bishop and his expedition from the American Alpine Club and National Geographic.

Barry Bishop Estate

“It was all cover,” Mr. McCarthy said.

Even so, Mr. McCarthy worried back then that the cover would be blown.

Already, climbers in Colorado were gossiping (correctly) that the expedition had a clandestine purpose. Mr. McCarthy fired off a letter to Mr. Bishop venting about “how this got out so damn quick.”

“Maybe we can put some kind of a stopper in someone’s mouth,” Mr. McCarthy wrote in a letter Mr. Bishop kept in his files.

Mr. Bishop wrote back from the Ashok Hotel in New Delhi, saying “You are right about climbers being supreme gossipers.” But he told his friend not to worry, because his plan had a “multiple-layer cover.”

Still, the Indians rejected the Kanchenjunga idea, saying it was in an “acutely sensitive” military area, according to Mr. Bishop’s files.

Then China detonated a second, even bigger, atomic bomb, injecting a new sense of urgency. It was full steam ahead — but first they had to find a new mountain.

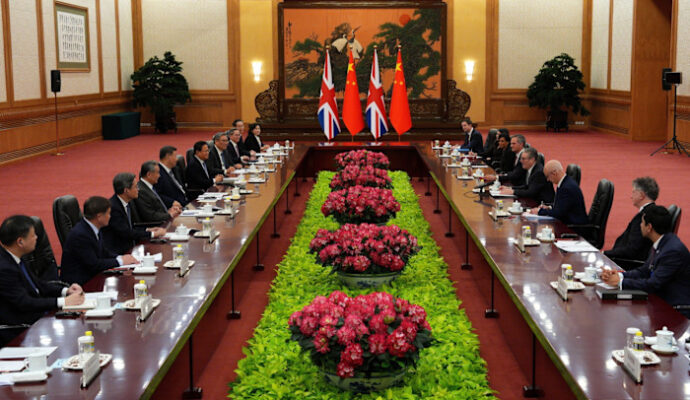

Nanda Devi is ringed by other mountains and known as one of the hardest to climb in the world.

Exhaustion, Nausea and Bitter Cold

Standing 25,645 feet high, Nanda Devi has a mythic, almost terrifying reputation.

It rises from a ring of white-toothed peaks like a forbidden mountain in an adventure book. Just hiking to its base is treacherous. At that point, only a handful of human beings had ever stood on its summit. Hugh Ruttledge, a famous prewar British mountaineer, said Nanda Devi was harder to reach than the North Pole.

But it offered a strategic location: within India and towering above the Chinese border.

The C.I.A. picked it, despite Captain Kohli’s reservations.

“I told them it would be, if not impossible, extremely difficult,” he said. Once again, he said, his concerns were dismissed.

On June 8, 1965, Mr. Bishop sent out a letter on the letterhead of the Mountain Research Group — his new cover.

“Dear Crew,” he wrote to the half-dozen climbers he had assembled. “All systems are go.”

The team flew off to Mount McKinley in Alaska for a quick practice run with the Indian climbers on the mission. The American team members were also taken to a secret government facility in North Carolina to familiarize themselves with explosives, in case they needed to blow holes in Nanda Devi to secure the telemetry station.

And they squeezed in clandestine training in Baltimore at the headquarters of Martin Marietta, the defense contractor that built the portable nuclear device.

According to declassified documents, the generator known as SNAP-19C (SNAP stands for Systems for Nuclear Auxiliary Power) was a terrestrial model, unlike the generators designed for America’s space program. Its radioactive fuel capsules were made at Mound Laboratories in Miamisburg, Ohio, and shipped out in July 1965 for unspecified “remote telemetry stations.”

Erecting the surveillance equipment during a test run on Mount McKinley in July 1965.

Captain Kohli’s archive

Mr. McCarthy spent hours practicing with the generator, bending over the machine, he said, gingerly balancing it between his legs, loading and unloading the seven tubular capsules that powered it.

“We were trained to do it fast,” he said. “At the time, I didn’t quite grasp the importance.”

Next stop: New Delhi. In mid-September 1965, the American climbers arrived at Palam Airport under the cloak of secrecy.

The Americans and the top Indian climbers, including Captain Kohli, were flown by helicopter to the foot of Nanda Devi, around 15,000 feet above sea level. As soon as they landed, Mr. McCarthy said, he told everyone to set up their tents and provide themselves with some food and water — immediately.

“I knew that we were going to be all sick as dogs,” he said.

Denied time to acclimate, the climbers got altitude sickness. Everything was being compressed into a very short timeline because late September was a risky time to mount a major Himalayan expedition. Winter and its ferocious storms were just around the corner.

The climbers and a team of Sherpas still faced a climb of more than 10,000 vertical feet, up a chain of camps along a ridgeline that withered to a knife’s edge. Mr. McCarthy remembers being dehydrated and cold, racked by headaches and extreme nausea, but staggering forward.

One source of solace, oddly enough, was the radioactive material. Plutonium 238 has a relatively short half-life, 88 years. It sheds heat. The porters jockeyed with one another to carry the plutonium capsules, Captain Kohli and Mr. McCarthy said.

“The Sherpas loved them,” Mr. McCarthy said. “They put them in their tents. They snuggled up next to them.”

Remembering this, Captain Kohli smiled, at first. “The Sherpas called the device Guru Rinpoche,” the name of a Buddhist saint, “because it was so warm,” he said with a laugh.

The climbing team that the American government flew to Mount McKinley for practice, in 1965.

Captain Kohli’s archive

But sitting in his study at home in the Indian capital, Captain Kohli’s eyebrows knitted with anger. The Sherpas were never told what the heat source was. He said that even the elite climbers were not well informed about the potential risks of carrying, much less sleeping next to, radioactive material.

“At the time,” he said, “we had no idea about the danger.”

‘99 Percent Dead’

Excerpts from a stack of handwritten notes in Mr. Bishop’s files capture the mission collapsing.

Oct. 4: “High winds.” “Tent was lost.”

Oct. 5: “Short of food.”

Oct. 11: “Snows all day.”

Oct. 13: “Very discouraging evening.”

Oct. 14: “Jim tried again to move up but again developed a severe headache.”

Oct. 15: “Almost constant snow.” “Frostbite.” “Coming to a crux.”

At this point, dozens of climbers and porters were manning their positions on the mountain’s southwestern ridge, packs stuffed, plutonium capsules loaded into the generator.

Handwritten notes from Mr. Bishop’s files.

Barry Bishop Estate

But on Oct. 16, as they tried to push for the summit, a blizzard hit. Sonam Wangyal, an Indian intelligence operative who was also an experienced mountain climber and, by all accounts, a very strong one, was huddled near the peak.

“We were 99 percent dead,” Mr. Wangyal remembered. “We had empty stomachs, no water, no food, and we were totally exhausted.”

“The snow was up to our thighs,” he said. “It was falling so hard, we couldn’t see the man next to us, or the ropes.”

Mr. Wangyal, now 83, lives behind the iron door of a small house tucked down a lane in Leh, the capital of India’s high-altitude Ladakh region. Even now, decades later, he was reluctant to say anything, worried that he could be put in jail for breaking his oath of silence.

But his resentment toward Captain Kohli seemed to get the better of him.

“Kohli didn’t know anything, he was sitting at base camp,” Mr. Wangyal grumbled. “If we hadn’t been experienced mountaineers, we would have all died.”

Mr. McCarthy said he had just come down from a carry — meaning, he had just lugged some supplies up to Camp Two — when he saw Captain Kohli standing by a rock at base camp, shouting into a walkie-talkie.

The C.I.A. had told the American climbers to leave all communication to the Indians. “They didn’t want American voices on the radio,” Mr. McCarthy explained. “There was a Chinese division right on the other side of Nanda Devi, for Christ’s sake.”

When he overheard Captain Kohli order the men to abandon the equipment at Camp Four and hurry back to base camp, Mr. McCarthy said he hit the roof.

“You have to bring that generator down!” he recalled shouting.

The two men glared at each other.

Mr. McCarthy never liked the fact that Captain Kohli was in charge. But since the operation was being conducted on Indian soil, he said that he and the other Americans on the mountain, including a C.I.A. officer waiting with him at base camp, were powerless to intervene.

“You’re making a huge mistake!” Mr. McCarthy recalled yelling at Captain Kohli before storming off.

“Every once in a while I get a glimpse of the future,” Mr. McCarthy said. “It’s happened a couple times in my life. It happened then. That generator was key. I could see them losing it. And I was right.”

Mr. McCarthy insists the climbers could have brought it down. “Oh God, yes,” he said. “The damn thing in its pack weighed 50 pounds. The Sherpas could take that.”

Mr. Wangyal disagrees. The conditions at the top were so treacherous, he said, that the trek between the camps, which usually took three hours, required 15 that day.

In a situation like that, he said, “you can’t carry an extra needle.”

Sonam Wangyal, one of the last surviving Indian climbers, photographed at an Indian Mountaineering Foundation conference in New Delhi, in November, said at the end of the mission they were “99 percent dead.”

The Indian climbers pushed the boxes of equipment into a small ice cave at Camp Four. They tied everything down with metal stakes and nylon rope. Then they scurried down as fast as possible. Captain Kohli said that he had maintained constant radio contact with his bosses in the Indian intelligence services and that they backed up all his decisions.

A few days later, the climbing season ended. The recovery mission would have to wait until the weather calmed down — months later, in the spring.

Gone

Captain Kohli and another C.I.A. team waited until May 1966, the next climbing season, to go back for the device.

But when the climbers scaled Nanda Devi and reached Camp Four, they were shocked. The generator wasn’t there. Actually, the whole ledge of ice and rock where the gear had been tied down wasn’t there.

A winter avalanche must have sheared it off, leaving nothing but a few scraps of wire.

The C.I.A. freaked out, Captain Kohli said.

“‘Oh my God, this will be very, very serious,’” he remembered C.I.A. officers’ telling him. “They said: ‘These are plutonium capsules!’”

Had he realized how dangerous it might be, he said, he would never have left the generator behind.

Captain Kohli said he tried his best to find it. He organized another search mission in 1967 and again in 1968. The team used alpha counters to measure for radiation, telescopes to scan the snow, infrared sensors to pick up any heat and mine sweepers to detect metal. They found nothing. They knew the device had to be somewhere on the mountain but couldn’t tell where.

Mr. McCarthy believes it “buried itself in the deepest part of the glacier.”

“That damn thing was very warm,” he said, explaining that it would melt the ice around it and keep sinking.

Despite the loss, the C.I.A. thanked the National Geographic Society for allowing Mr. Bishop to work on the mission, calling his involvement “indispensable.” In a letter found in the archives of the Lyndon B. Johnson Library, a National Security Council official expressed “the gratitude of our government” for permitting Mr. Bishop to assist “a unique priority project which concerns the security of the United States.”

Source: Lyndon B. Johnson Library

The C.I.A. kept pushing to set up a mountaintop station to spy on China. It tried other mountains in India, lower and easier to climb.

According to Captain Kohli and the once-secret Indian government documents, a team of climbers finally managed to install a new batch of surveillance equipment, powered by radioactive fuel, on a flat ice shelf on a lower summit, near Nanda Devi, in the spring of 1967.

A nuclear-powered device that was installed by C.I.A. climbers on another mountain near Nanda Devi. It’s the same as the model that is still missing.

Rob Schaller, via Pete Takeda collection

But the Himalayan snows constantly buried it, cutting off signals it might have picked up. Once, when Indian climbers scaled back up to see what was wrong, they were astonished by what they found.

The warm generator had melted straight through the flat ice cap, Captain Kohli said. It sat in a strange cave, like a tomb, several feet under the snow, burrowing itself deeper and deeper into the ice. It was as if the device was hiding itself.

That sputtering telemetry station was shut down in 1968, with the equipment retrieved and sent back to the United States, according to Indian documents. But the C.I.A. still didn’t give up.

Climbers fighting their way up another peak near Nanda Devi.

Captain Kohli’s archive

According to Captain Kohli, who wrote a book about his clandestine work, “Spies in the Himalayas,” the C.I.A. set up a snooping device in 1973 that worked well, picking up signals from a Chinese airborne missile.

But by the mid-1970s, the United States was fielding a growing constellation of spy satellites. The new technology could intercept a whole world of signals from space. A small antenna on a mountaintop now was totally obsolete.

‘Serious and Embarrassing’

The whole mission remained a secret for more than a decade, and it might have stayed that way if not for a relentless young reporter.

Howard Kohn had broken some major stories in the 1970s, including an exposé in Rolling Stone on the death of a nuclear activist, Karen Silkwood. The Silkwood story led him to people on Capitol Hill, who led him to a bulldog of a congressional investigator, who ultimately led him to the mystery on Nanda Devi.

“I was just taken aback at the fact that the C.I.A. knew no bounds,” recalled Mr. Kohn, who started digging into the story in early 1978 for Outside magazine, which was then a little-known offshoot of Rolling Stone.

Howard Kohn, who broke the story in the 1970s about the missing generator, at his home in Takoma Park, Md., in 2022.

Jason Andrew for The New York Times

He said the climbers he spoke to at the time felt bitter about the mission and pointed him in the same direction: to Mr. Bishop.

Mr. Kohn showed up at Mr. Bishop’s home on Millwood Road in Bethesda, Md., the same address he had used for his so-called scientific expeditions. According to Mr. Kohn, Mr. Bishop tried to deny the whole thing but eventually admitted his role and broke down. Mr. Kohn said he begged to be left alone, saying that if it ever got out that he had worked for the C.I.A., his reputation as a National Geographic photographer would be ruined.

Mr. Kohn said Mr. Bishop claimed to have voiced doubts about the mission, but said the C.I.A. warned him: “‘You can’t back out now.’”

“They treated everyone like pawns,” Mr. Kohn said.

After the interview, Mr. Bishop sent telegrams to Jann Wenner, the co-founder of Rolling Stone, and William Randolph Hearst III, the newspaper heir who was managing editor of Outside at the time, warning them not to use his name.

“The Nanda Devi Caper” story broke on April 12, 1978, without mentioning Mr. Bishop or the other climbers’ names.

That same day, two Democratic congressmen, John D. Dingell of Michigan and Richard L. Ottinger of New York, wrote to President Carter.

“If the article is in fact accurate,” their letter said, “we strongly urge that this nation take whatever steps may be necessary to resolve this serious and embarrassing situation.”

Source: C.I.A. archives

At a follow-up news conference, the congressmen made another point: The U.S. Navy had searched exhaustively for a pair of SNAP-19B2 generators that disappeared off the Californian coast in 1968 when a weather satellite crashed. The government was so anxious to recover them that the Navy sent half a dozen ships and plumbed the ocean for nearly five months until they were found.

Why, then, had the Americans simply packed up in India, leaving a similar nuclear device lost in the Himalayas?

The White House struggled to respond. A declassified memo to Mr. Carter from Warren Christopher, then acting secretary of state, said that Mr. Kohn’s story was “correct in major respects.” But American officials did not acknowledge that publicly.

Mr. Kohn’s article for Outside Magazine in 1978 was the first public disclosure of the secret mission.

Jason Andrew for The New York Times

“We are taking the standard public position that we do not comment on allegations relating to intelligence activities,” Mr. Christopher informed Mr. Carter.

That phrase is nearly identical to what the State Department recently told The Times when asked about the mission: “As a general practice, we don’t comment on intelligence matters.”

Mr. Christopher predicted that the Indian government would be “particularly concerned with the possible environmental impact” of losing a nuclear device so close to the headwaters of the Ganges.

He was right.

The Secret Cables

“It was an uproar,” said Mr. Yadav, the former Indian intelligence officer.

The Indian climbers had kept their word, he said, and very few Indian officials knew about the mission, even inside India’s spy services.

So when the news hit New Delhi, the nation was blindsided. India’s foreign ministry summoned the American ambassador. Protesters took to the streets, waving signs that said, “C.I.A. is poisoning our waters.’’

Indian lawmakers called for an investigation, demanding to know where the device was, who had approved the mission and why. Opposition leaders harassed the prime minister on the floor of Parliament, accusing him of collaborating with “the notorious C.I.A.”

The Indian government’s report from 1979 on the missing nuclear device. Captain Kohli provided The Times with a copy.

That was a particularly damaging charge. India, after all, was supposed to be the leader of the world’s nonaligned movement, which refused to back either side of the Cold War, Washington or Moscow. Now its government was being exposed for doing the C.I.A.’s bidding on its own soil — and doing it poorly, no less.

The biggest concern was the Ganges. Nanda Devi’s glaciers, formed millions of years ago, feed tributaries of the river, which runs more than 1,500 miles and nourishes a vast, fertile ecosystem where hundreds of millions of people live.

Within days, Mr. Desai, India’s understated prime minister, stood in front of Parliament and assured the nation that there was “no cause for alarm.”

But to be “triply sure,” he said, according to India’s parliamentary archives, he was appointing a committee of experts to investigate the risks posed to “the waters of our sacred river Ganga.”

The United States had urged the Indian government not to admit that the operation happened at all, according to diplomatic traffic in the State Department’s archives. Mr. Desai mostly played along. In his performance before Parliament, he didn’t mention the C.I.A. or cast any blame on the United States.

The American ambassador was relieved. He sent a confidential cable to Washington, praising Mr. Desai for defusing “an increasingly emotional issue” and urging Mr. Carter to slip in a few “words of appreciation” in his next letter to the Indian leader.

Mr. Carter did exactly that. In a secret missive to Mr. Desai, dated May 8, 1978, he wrote, “May I express my admiration and appreciation for the manner in which you handled the Himalayan device problem,” describing it as an “unfortunate matter.”

Mr. Carter had been trying to delicately rebuild relations with India. For years, the United States had been vilified by Indira Gandhi, the prime minister and scion of India’s political dynasty who brought India more into the Soviet orbit. But Indira Gandhi had been recently voted out. Mr. Desai was in. And he was much more open to cooperating with Washington.

A few weeks later, Mr. Desai walked into the White House. A photograph shows him dressed in a crisp blue jacket and the narrow white hat of his generation, sitting in the Oval Office across from a beaming Mr. Carter. A dozen aides squeezed around.

Jimmy Carter with Prime Minister Morarji Desai of India in the Oval office in 1978.

HUM Images/Universal Images Group, via Getty Images

The two leaders talked about Cuban troops lingering in Ethiopia and the possibility of the Soviets moving into Afghanistan. They discussed trade and America’s push to make South Asia a nuclear-free zone.

And, of course, they spoke about the missing device. According to a formerly secret document in State Department records, Mr. Carter told Mr. Desai that “he was glad that neither of them had been involved” in the mission, which had happened years before they took office. Even so, they had been thrust together to clean up the mess, and scholars are struck by how well they cooperated.

“This was the kind of thing that you could have made a big deal out of — that the C.I.A. was messing around with plutonium in the Himalayas,” said Gary Bass, a historian at Princeton who reviewed the decades-old secret cables shared by The Times.

Instead, he said, “they both work to hush it up.”

Joseph Nye, the American foreign policy guru who coined the term “soft power,” was in the room when the two leaders met.

Mr. Nye died recently, at age 88, but in an interview with The Times last year, he recalled the meeting vividly. Back then, he was a 41-year-old deputy under secretary specializing in nuclear nonproliferation.

He said that the two leaders didn’t bring up the missing device in the bigger meeting and waited until they were in private to talk about it. “It was a highly classified intelligence issue,” he said, and it would have had “a code word to refer to it.”

The State Department and the C.I.A. maintain their public silence to this day. But the failed mission keeps surfacing in the archives, often in the same anodyne words.

The whole thing is simply chalked up as “the Himalayan Incident” or “the Nanda Devi Affair.”

‘Run!’

On Feb. 7, 2021, a giant wedge of rock broke off from a mountain near Nanda Devi and came crashing down. It unleashed a surge of water, mud, ice and more rock that thundered through the narrow Rishiganga gorge.

Amrita Singh was sprinkling fertilizer on her family’s silkworm farm in a nearby village, Raini, where the houses cling to the hillsides and rows of red beans and wheat cut like steps into the slopes. All of a sudden, other villagers started screaming, trying to get her attention. The landslide was plunging straight toward her.

“Get out of there!” villagers yelled to Ms. Singh. “Run!”

It was too late. Amrita was swept away.

The village of Raini along the route up to Nanda Devi, in 2022.

Weeks later, sniffer dogs found her body. More than 200 other people were killed. Many were workers at a hydropower dam that stretched across the river. The surge of water was so titanic that the dam was swept away as if made of sand.

“It has to be that generator,” Captain Kohli said, blaming the heat it threw off. He conceded that he had no proof but asked, “What else can there be?”

Many villagers living in the string of settlements leading up the trail to Nanda Devi suspected the same thing. Nanda Devi has been closed to climbers for years, but villagers know that a nuclear device that their government doesn’t want to talk about was lost nearby.

“We initially thought that probably this thing exploded,” Dhan Singh Rana, a farmer who wrote environmental articles, told The Times before he died in 2023.

Eventually, he seemed to accept what some scientists said — that global warming contributed to an enormous crack in the glacier, and that’s what ultimately caused the landslide and the flood. But, he said, “even if the device doesn’t explode, it is still out there, and that in itself creates a sense of fear.”

“If people can go to the moon,” he asked, “why can’t they find out what happened to this device?”

Questions haunt the villagers: How dangerous is the missing device? Could it poison the headwaters of one of the world’s largest rivers?

The Indian government tried to dismiss these fears in the 1970s. A committee of experts appointed by Prime Minister Desai said in 1979 that the device was still missing, but that water samples from the area showed no traces of contamination. (It is unclear if anyone has searched for the device since then, and local officials say it has never been found.)

The committee concluded that even in the worst scenarios, like the generator cracking open and the plutonium capsules flying out, the risks of radiation poisoning the water supply were “negligibly small.”

Dhan Singh Rana in Lata village in 2022. “If people can go to the moon,” he asked, “why can’t they find out what happened to this device?”

Scientists today tend to agree, given the vast amounts of water flowing into the Ganges. But they still worry about the risks to local residents. As global warming accelerates and all sorts of forgotten histories surface from the ice — animal fossils, old equipment, even the corpses of long-lost climbers — people in this area could find a strange metal contraption, warm to the touch, lying in the snow at their feet.

Plutonium, if swallowed or breathed in, can cause internal damage and form toxic compounds in a person’s body, said David Hammer, a professor of nuclear energy engineering at Cornell University who reviewed some of the formerly secret scientific documents.

A few hints of the possible dangers are contained in a once-classified report from 1966 on a similar secret device, a SNAP 19-C2. The U.S. Navy placed that one on a remote rock island in the Bering Strait, apparently to spy on Soviet submarines prowling around Alaska.

Anyone attempting to recover it, the 1966 report warned, needs to approach the area from an upwind direction and “be equipped with self-contained breathing apparatus or ultra-filter, full-face respirators.”

In this case, Dr. Hammer believes the biggest danger is a dirty bomb.

He and other nuclear scientists said that if the generator’s capsules ended up in the wrong hands, they could be used to make a weapon that spreads panic by blowing up radioactive matter and spewing radioactive dust.

The missing plutonium, he said, represents “quite a lot of material.”

It is not clear what happened to the Nanda Devi porters who curled up with the capsules, trying to stay warm. Mr. McCarthy said he came down with testicular cancer in 1971. He blames the generator.

“There’s no history of cancer in my family, none, going back generations,” he said. “I have to assume that after loading this goddamn thing, I was exposed.”

“We weren’t that stupid,” he said. “We had asked the engineers about radiation. They lied to us. They told me it was completely shielded. That thing should have weighed 100 pounds if it were completely shielded. It weighed 50.”

The Fears Must Be ‘Put to Rest’

The past is now colliding with India’s future.

Hungry for electricity, India is damming rivers across the Himalayas and widening mountain roads. It’s building high-altitude army outposts along the China border, a contested area where Indian and Chinese troops have fought deadly hand-to-hand brawls.

“A lot of activities are going on in that area,” said Satpal Maharaj, the tourism minister for Uttarakhand, the mountainous state where Nanda Devi sits.

“The radioactive material is right there, inside the snow,” he said. “Once and for all, this device must be excavated and the fears put to rest.”

Nanda Devi, in the background, has been closed to climbers for years.

Mr. Maharaj met with India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, in 2018 to discuss the problem. Mr. Modi seemed unaware of what had happened in 1965, Mr. Maharaj said, but promised to look into it. Mr. Modi’s office did not respond to repeated requests for information, and a spokesman for India’s Department of Atomic Energy said the agency did not have “any information regarding the missing device.”

The authorities in Uttarakhand have been musing about reopening Nanda Devi to climbers. But a new round of articles in July in the Indian press reminded people of the “aborted secret mission” and the possibility of radioactive contamination.

That month, Nishikant Dubey, a member of Parliament from Mr. Modi’s party, put out a statement on social media questioning whether the missing device was responsible for a string of natural disasters.

In an interview, Mr. Dubey explained that on a recent trip to the Himalayas, he had heard many accounts of landslides, floods and houses collapsing. So, he said, he “started digging.”

He ran across some of the old C.I.A. documents and now believes that the generator is “very dangerous” and that the agency needs to come back and find it.

“Who owns that device should take out that device,” he said.

Mr. Yadav, the former spy, has become even more fixated. He has combed through archives, conducted interviews and joined the small group of people who, like Captain Kohli and Pete Takeda, a well-respected American climber, have written entire books on the mission.

“This is a grave danger, lying there for all humanity,” Mr. Yadav said in Delhi.

“I know what the scientists say,” he said. “But I tell them, ‘I’ll give you Pu-238 in a glass of water and you drink it.’”

He laughed.

“They’re all paper tigers,” he said.

Brent Bishop had wondered for years about his father’s role in the mission. He’s an accomplished climber, too, and when his father was still alive, he asked him about Nanda Devi.

His father acknowledged his involvement, Brent Bishop said, “but didn’t want to talk about it.”

Then, just last month, he was visiting his mother when he found a box of his father’s files on a metal shelf in the garage labeled “smaller expeditions and projects.”

The box held many of the mission’s secrets.

“I’m proud of what he and the team did — or tried to do,” Brent Bishop said. “This group of men had a unique skill set that they were able to use to benefit the country, even if things didn’t go as planned.”

Captain Kohli felt differently.

Captain Kohli at one of his homes said the CIA never listened to his concerns.

As a leader of the daring escapade, he knew more about what happened on that mountain, 60 years ago, than just about anyone.

But in an interview at his home in New Delhi before he died, as a sultry afternoon faded into evening, it was clear that he regretted it.

“I would not have done the mission in the same way,” he said.

“The C.I.A. kept us out of the picture,” he said. “Their plan was foolish, their actions were foolish, whoever advised them was foolish. And we were caught in that.”

His gaze drifted off, past the chest of climbing medals in his hallway and the painting of a Himalayan mountain jutting into a deep blue sky.

“The whole thing,” he said, “is a sad chapter in my life.”