On a recent trip to mainland China, I found myself posing the same question, again and again, to the economists, technologists and business leaders who I met with. “Trade is an exchange. You provide something of value to me, and in return, I must offer something of value to you. So what is the product, in the future, that China would like to buy from the rest of the world?”

The answers were revealing. A few said “soyabeans and iron ore” before realising this was not much help to a European. Some observed that Louis Vuitton handbags are popular and then went on to talk about the export prospects for fast-rising Chinese luxury brands. “Higher education” was another common answer, qualified sometimes with the observation that Peking University and Tsinghua are harder to get into, and more academically rigorous, than anything on offer in the west.

Several of the economists, who had perhaps pondered the issue already, jumped ahead to a different point altogether: “This,” they said, “is why you should let Chinese companies set up factories in Europe.”

It is a train of thought that gives away the real answer to the question. Which is: nothing.

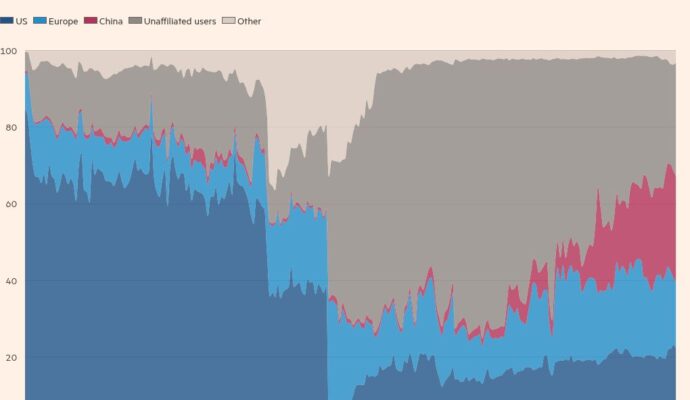

There is nothing that China wants to import, nothing it does not believe it can make better and cheaper, nothing for which it wants to rely on foreigners a single day longer than it has to. For now, to be sure, China is still a customer for semiconductors, software, commercial aircraft and the most sophisticated kinds of production machinery. But it is a customer like a resident doctor is a student. China is developing all of these goods. Soon it will make them, and export them, itself.

“Well, how can you blame us,” the conversation usually continued, after agreeing on China’s desire for self-sufficiency, “when you see how the US uses export controls as a weapon to contain us and keep us down? You need to understand the deep sense of insecurity that China feels.”

That is reasonable enough and blame does not come into it. But it leads to the following point, which I put to my interlocutors and put to you now: if China does not want to buy anything from us in trade, then how can we trade with China?

This is not a threat but a simple statement of fact. Workers in Europe, Japan, South Korea and the US need jobs. We do not want our economic development to go into reverse. And even if we did not care, without exports, we will eventually run out of ways to pay China for our imports. In a different context, Beijing policymakers do recognise this: they worry about a devaluation or default on the mountain of dollar assets China has already accepted.

The drag on the rest of the world was well illustrated when Goldman Sachs recently upgraded its forecast for the size of China’s economy in 2035. Normally, a growth upgrade in any country benefits all others: there is more demand, more consumption and more opportunity. Yet in this case, the extra Chinese growth comes from exports, taking markets from other countries. Germany will suffer the most, according to Goldman, with a drag of around 0.3 percentage points on its growth over the next few years.

So how should China’s partners respond to its explicit intention not to trade with them as equals? To its mercantilist determination to sell but not to buy?

The only good solutions lie with Beijing. It could take action to overcome deflation in its own economy, to remove structural barriers to domestic consumption, to let its exchange rate appreciate and to halt the billions in subsidies and loans it directs towards industry. That would be good for the Chinese people, too, whose living standards are sacrificed to make the country more competitive.

But outsiders have been requesting as much for decades. Whatever lip service may get paid to this, the Central Committee’s recommendations for China’s next five-year plan should temper any hope of change. Consumption is on the priority list, at number three. Items one and two are manufacturing and technology.

That leaves one difficult solution and one bad solution for Europe. The difficult solution is to become more competitive and find new sources of value, as the US does with its technology industry. That means more reform, less welfare and less regulation: not because welfare and regulation are bad per se, but because they are unaffordable given the competition.

Even that, however, will not be enough in a world where China offers everything cheaply for export and has no appetite for imports itself. There will simply be no alternative but to rely on domestic demand. Which leads to the bad solution: protectionism. It is now increasingly hard to see how Europe, in particular, can avoid large-scale protection if it is to retain any industry at all.

This path is so damaging and so fraught it is hard to recommend it. China absorbed US tariffs, but the US is the only country it regards as an equal, and Beijing is likely to respond aggressively against anyone else who erects trade barriers. It would mark a further breakdown of the global trade system.

Yet when the good options are gone, the bad are all that is left. China is making trade impossible. If it will buy nothing from others but commodities and consumer goods, they must prepare to do the same.