China’s green bond market has overtaken western rivals for the first time this year, as Beijing embraces a form of sustainable finance coming under growing pressure in the US and Europe.

In 2025, China issued a record $70.3bn of bonds either certified or aligned with the Climate Bonds Initiative, an international organisation, according to Financial Times calculations based on LSEG data.

This has helped China’s energy transition outpace other countries as the ESG movement — finance and investment to support the environment, sustainability and good governance — faces a backlash led by Donald Trump’s America.

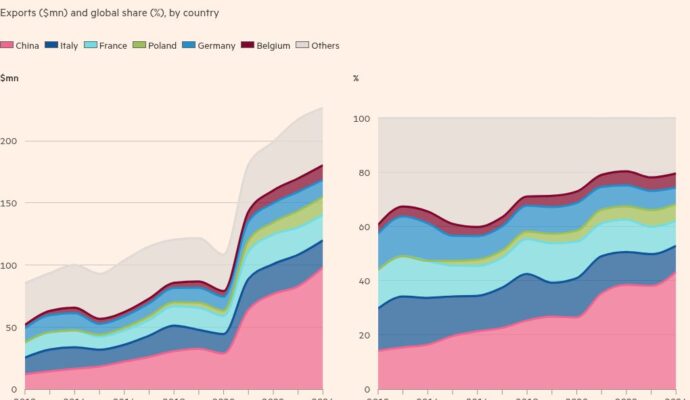

China has accounted for more than 17 per cent of global green bond issuance this year while the US made up 3 per cent.

“The US is no longer there and Europe is struggling,” said Alicia García-Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist at Natixis. “There’s a kind of fatigue in the European ESG market.”

Green bonds are a form of debt issued by companies and sometimes governments where the proceeds are earmarked for spending on environmental projects. They gained popularity — particularly in Europe — over the past decade as asset managers, keen to burnish their ESG credentials, piled into sustainable investment strategies, sometimes rewarding “green” borrowing with lower financing costs.

But the trend has reversed as Trump’s stance has damped the finance industry’s enthusiasm for ESG, including in Europe.

“China is obviously the only region that is still ramping up,” said Crystal Geng, head of ESG research for Asia at BNP Paribas Asset Management.

Beijing has committed to carbon emissions peaking in 2030 and to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. The country is building about three-quarters of global wind and solar projects. It leads the world in hydropower, renewable energy storage and transmission and green hydrogen facilities. It has far and away the biggest number of nuclear power plants under construction.

Such investment is becoming an important source of economic growth, as China battles a slowdown triggered by the collapse of its real estate sector.

Most of China’s large sustainable projects are not funded by green bonds. According to the People’s Bank of China, the country has Rmb43.51tn ($6.1tn) of outstanding green loans, compared with about Rmb2tn of outstanding green bonds.

One reason is that many borrowers for green projects are small and medium-sized businesses. These companies do not have credit ratings and cannot tap the green bond market.

Nevertheless, experts expect China to increase its issuance of green financial instruments to meet the funding needs of the energy transition. For example, the country needs to add an estimated 6,000 gigawatts of power capacity over the next 25 years, at a cost of between $12tn and $14tn, said Robert Gilhooly, senior emerging markets economist at Aberdeen.

García-Herrero said Chinese issuance of relatively low-cost green bonds was likely to grow because the profits made by many of the industries, such as solar panels, are shrinking rapidly.

“They don’t have organic sources of funding, which means they need to go to the market more than ever,” she said.

The PBoC launched China’s green bond market a decade ago. Many projects, particularly large-scale infrastructure, require long-term financing but banks were reluctant to lend on such time horizons, said Ma Jun, a former PBoC chief economist and founder and president of the Beijing-based Institute of Finance and Sustainability.

“We decided to create a green bond market, largely because of the mismatch of maturity problem for the banking system,” Ma said.

Alain Naef, assistant professor at the ESSEC Business School in Cergy in France, said cheap finance meant green projects in China do not have to be as profitable as conventional ones — or as green projects in other countries.

Western authorities, he noted, have been unable to offer the same support because green finance is viewed as a political issue and central banks must be regarded as market neutral.

“In China there’s no such thing,” Naef said. “The central bank can publicly and overtly support such projects.”

China has long sought to attract foreign capital to invest in its green bonds. But foreign investors have been cautious about the asset class because of perceived risks over greenwashing and fears that they may not be able to sell the bonds in secondary markets.

Most investors in China’s green bond market are domestic institutions, said Angela Cheng, head of research and chief macro strategist at CGS International Securities.

“It’s mainly commercial banks, insurance companies, asset managers,” Cheng said.

Policymakers hope this will change. China’s green bond taxonomy — the terms and conditions that qualify a bond as green, an important consideration for ESG investors — is now in line with global standards, said Christoph Nedopil Wang, director of the Griffith Asia Institute at Griffith University of Queensland, Australia.

“China can distinguish itself to be a force for climate action compared with the US, which is a force for climate inaction.”