Alpha Wong was acting on what he viewed as a clear commitment from British authorities when he moved with his mother and sister from Hong Kong to the London borough of Sutton three years ago.

The software engineer trusted official assurances that he and other holders of British National (Overseas) passports issued to Hongkongers would qualify for permanent settlement in the UK five years after arrival. Full British citizenship would be available a year later.

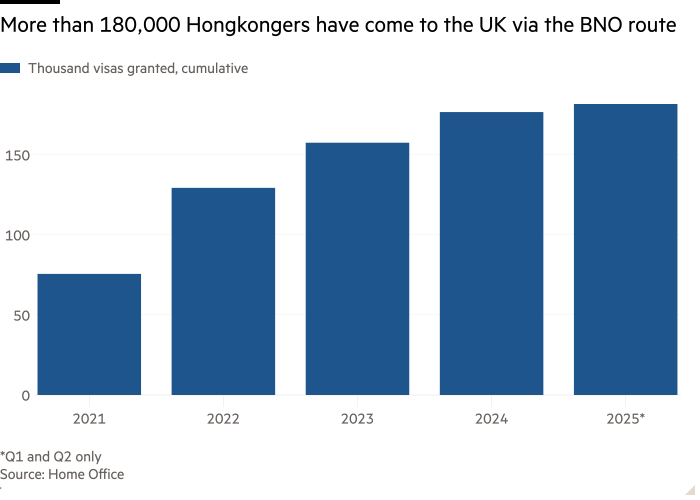

But like many of the more than 180,000 people who have used a visa scheme for holders of BNO passports to move to the UK, Wong, 33, fears he is now being caught up in a domestic political backlash against immigration.

Proposals set out by the government last month, in a bid to fend off Nigel Farage’s Reform UK, would delay permanent settlement for most immigrants until 10 years after arrival. Citizenship would take another year.

Hongkongers and their advocates say extending their path to settlement and citizenship would lead to significant practical consequences, including delays accessing their Hong Kong pension funds.

Wong also expressed deep disillusionment that Britain, which governed Hong Kong for more than a century until 1997, had fallen short.

“We thought that the UK would open up to us,” Wong said, sitting in a café on Sutton’s busy high street. “We thought that there will be real commitment. Because we know that the UK really values contracts, we thought that the lifeboat would be really stable.”

His views were echoed by Matthew, a Hongkonger who moved to Sutton with his wife in 2021. Matthew, who declined to give his surname, said the couple had chosen the UK because its immigration policies seemed easier to navigate and more predictable than those in Australia and Canada.

But, referring to the UK’s planned settlement timetable changes, he added: “If they can change it from five to 10 years, they can change anything, just like Canada and Australia.”

The most pressing practical worry, meanwhile, is that Hongkongers will be deprived of savings from their Mandatory Provident Fund (MPF) pension pots in the Chinese territory until they become UK citizens.

Heather Rolfe, senior research fellow at the think-tank British Future, noted that Hong Kong’s government allowed MPF providers to release funds to people who had left only if they had secured new citizenship.

Hong Kong Watch, a pressure group, has said MPF providers are withholding more than £3bn in savings from BNO holders now in the UK.

“They can’t claim their Hong Kong contributory pension until they can prove that they’re permanently settled somewhere,” Rolfe said. “It won’t pay out until they obtain another citizenship.”

The Hongkongers’ position reflects the complexities of the UK’s many shifts in immigration policy in recent years. Former premier Boris Johnson’s Conservative government launched the BNO visa scheme in 2021, at the height of unrest over the introduction of a contentious National Security Law.

The legislation, which criminalises many forms of dissent in Hong Kong, provoked demonstrations attended by as many as 2mn of the territory’s 7.5mn population and a violent police response.

The visa is open to roughly 2.9mn people who were eligible for the BNO passport issued to Hongkongers before the territory’s 1997 handover from the UK to China and to their children.

The UK was a popular choice for those fleeing thanks to a widespread nostalgia for how the territory was governed under British rule.

Some 5,000 people from Hong Kong have moved to Sutton attracted by its combination of good schools and house prices lower than other parts of the capital.

There are other sizeable communities around south-west London, in Hendon in north London, in the Solihull area of the West Midlands and Warrington in Greater Manchester, among others.

Richard Choi, a Liberal Democrat councillor on Sutton council who moved from Hong Kong in 2008, said the shift in migration policy had infuriated Hongkongers in the borough.

As well as the pensions issue, many of the Sutton Hongkongers are angry that a delay in achieving permanent settlement — known as indefinite leave to remain — could force them to pay far higher international fees for their children’s university education.

“The UK government said there was a path to permanent residency,” Choi said. “People signed up because of the promise. Right now, in the middle of the process, [the government] are talking about a change. [Hongkongers] are very angry about that.”

There remains a chance that the final legislation on the new process will be changed to leave rules unchanged for Hongkongers and other groups already on the way to settlement in the UK.

Colin Yeo, an immigration barrister, said it would be “just not fair” if ministers applied the proposed new rules to people who moved to the UK on the promise of a far quicker path to permanent residency.

“They made a decision to move to this country on that basis and to give up their homes and their jobs and then they find that the rules get changed,” Yeo said.

The Home Office stressed that the new legislation would still be subject to a consultation period and that it was in contact with representatives of the Hong Konger community about their concerns.

“We will always welcome those who make a positive contribution to our country, because settlement is a privilege rather than a right,” the department said. “A consultation on settlement reform will launch later this year, with further details to follow.”

Yet Wong expressed deep disappointment that the UK’s commitment to people who had fled Hong Kong seemed to be wavering. He had understood his BNO passport as a guarantee of a “Plan B” if Chinese rule of the territory went wrong, something many Hongkongers now feel has come to pass.

“They said, ‘We’ll give you a passport’,” Wong said. “They said it was a life-long commitment.”

He had not expected the terms of the commitment to be redrawn, he added.

“I didn’t think that the government would get away with this,” he said.

Data visualisation by Ella Hollowood