Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

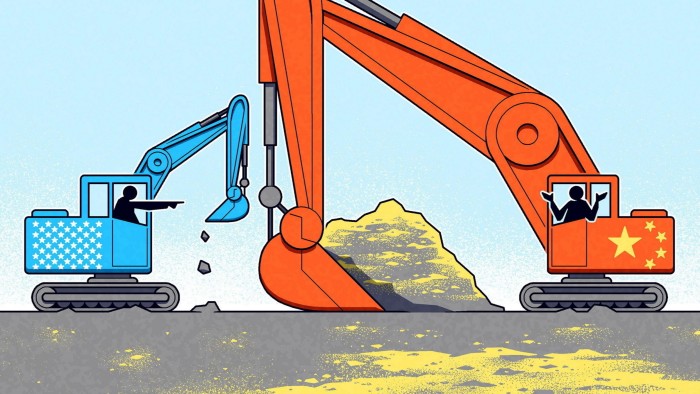

It’s hard to watch the US-China conflict over rare earth minerals as anything other than shadow boxing. The implications of the fight are very real. China’s ringfencing of critical minerals and its export controls on the sector, which are needed for everything from semiconductors and electric vehicles to smartphones and fighter jets, is a big hit to the US. But the shock both sides profess to have about the situation is pure theatre.

US Treasury secretary Scott Bessent said last week that China’s leveraging of export controls on the minerals was the result of “rogue” trade actions in advance of a planned Trump-Xi summit, and that Beijing “couldn’t be trusted”.

Perhaps, but the reality that China had this card to play is down to the fact that the US has, for the past 30 years, allowed it to slowly but surely take over the entire industry.

China never made any secret of its desire to do so. In 1992, Deng Xiaoping announced the country’s desire to turn rare earths into the “oil” of China. In the mid-1990s, amid a general deregulation of global trade that led to more permissive investment screening and tolerance of offshoring, the US Committee on Foreign Investment in the US, under the Clinton administration, approved General Motors’ sale of Magnequench — an Indiana-based company that manufactured the rare earth magnets used in computer hard drives, consumer electronics and jet guidance systems — to Chinese owners with close ties to the government.

The fact that these magnets had a “dual use”, meaning that they could have both military and commercial applications, is the only reason that the merger got a close look to begin with. (One Pentagon consultant said the company was targeted to improve Chinese cruise missile technology.) The Cfius approval was based on a promise that the factory would stay in Indiana.

It didn’t. After a few years, the entire Indiana operation was shut down, and production and equipment were moved to China. As representative Peter Visclosky, a Democrat from northern Indiana, said in 2004 when the last plant was shuttered: “We’re handing over to the Chinese both our defence technology and our jobs in the midst of a deep recession.”

The George W Bush White House did nothing to stop it. In 2005, a US-China Economic and Security Review Commission report noted the deal and that the closure “allowed China to come closer to cornering the market in rare earth minerals”.

But it wasn’t only a lead in production that the US willingly gave up — it also failed to protect its access to raw materials.

Until the late 20th century, the US was the world’s leading producer of rare earth minerals, mainly through the Mountain Pass mine in California, which opened in 1952. Stricter environmental standards, lower productivity and a lack of support for industrial policy in the US led to its closure in 2002. Mountain Pass was eventually reopened in 2012, but by then the Americans had no domestic refining capacity and had to ship their raw materials to China for processing.

By this point, China had leveraged its usual state power control combination of low-cost production and extraction, cheap loans and export limits to bring the majority of the world’s critical mineral industry under its domination. (This same strategy was used to ringfence the global maritime industry and many other sectors.)

It also began leveraging critical minerals geo-economically, belying today’s complaints from Beijing that the rare earth squeeze is simply blowback from a US Department of Commerce decision to expand the number of Chinese companies on its blacklist in late September.

In fact, the Chinese first used rare earth export controls to curtail shipments to Japan in 2010, after a diplomatic dispute between the two nations. The US, EU and Japan challenged Chinese rare earth export restraints at the World Trade Organization in 2012. They won, but by then it didn’t matter. The industry was already largely in China, and the west had yet to recommit to policy around it in a serious way.

China hawks, defence personnel and labour advocates in the US have, for many years now, been pointing out the Chinese rare earth mineral chokepoint that was hiding in plain sight.

Back in 2020, during Senate testimony, US-China commissioner Michael Wessel noted statements from a Chinese government-funded research institute that said: “Amid the heated trade conflict between China and the United States, China will not rule out using rare earth exports as leverage to deal with the situation.”

And here we are. Last year, Bessent derided President Joe Biden’s support for strategy sectors as “central planning” (aside from bolstering semiconductors and clean tech, the Biden administration provided funding to Noveon Magnetics, the only rare earth magnet manufacturer in the US).

This year, the Trump White House is doubling down on that approach, pouring hundreds of millions of dollars in investments and loans into jump-starting critical mineral mining and production in the US.

The only surprise in all of this is that it took so long. I predict both the shadow boxing — and the race to rebuild strategic sectors — will continue.