Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

How stands the world economy? The answer, as my colleague Tej Parikh noted recently, is that it is confusing. That should not be surprising. Quite apart from some evident macroeconomic uncertainties — disturbing trends in fiscal deficits and debts in many important countries, to take one example — we are witnessing two huge events: the abdication of the US as global hegemon and the uncontrolled onset of what could prove to be the most important of all humanity’s technological innovations, artificial intelligence. No wonder we are confused. The remarkable thing, however, is how well the world economy has coped with the shocks and the uncertainty, at least so far.

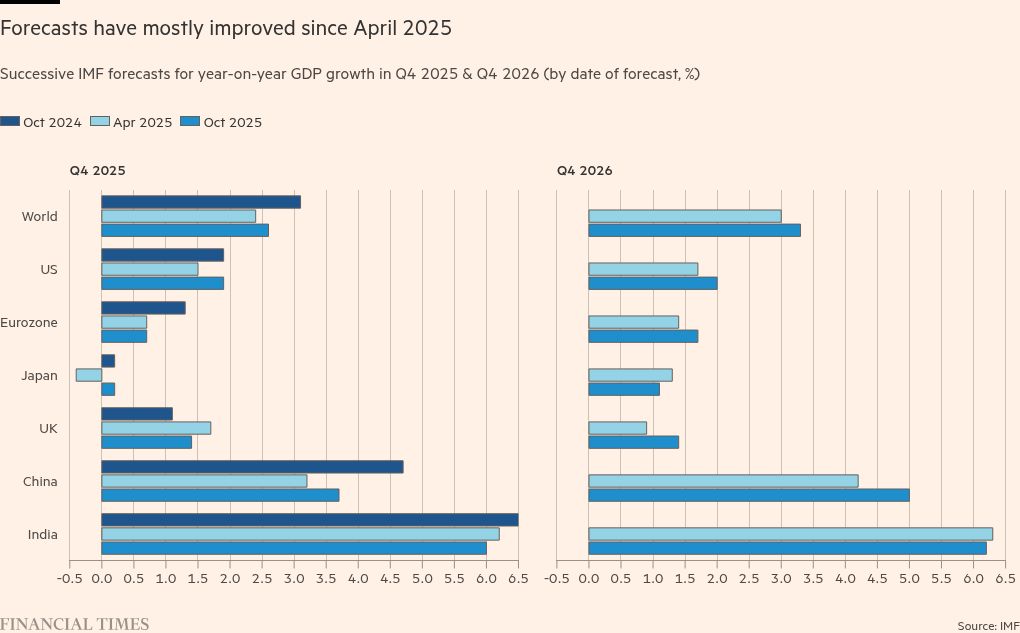

This is a leading theme of both the introductory speech of Kristalina Georgieva, IMF managing director, to this year’s annual meetings in Washington and the latest World Economic Outlook. The big conclusion is that the IMF sees growth slowing relatively little this year and next. Needless to say, any such conclusion is itself highly uncertain. But it is consistent with what has happened so far this year, despite the turmoil.

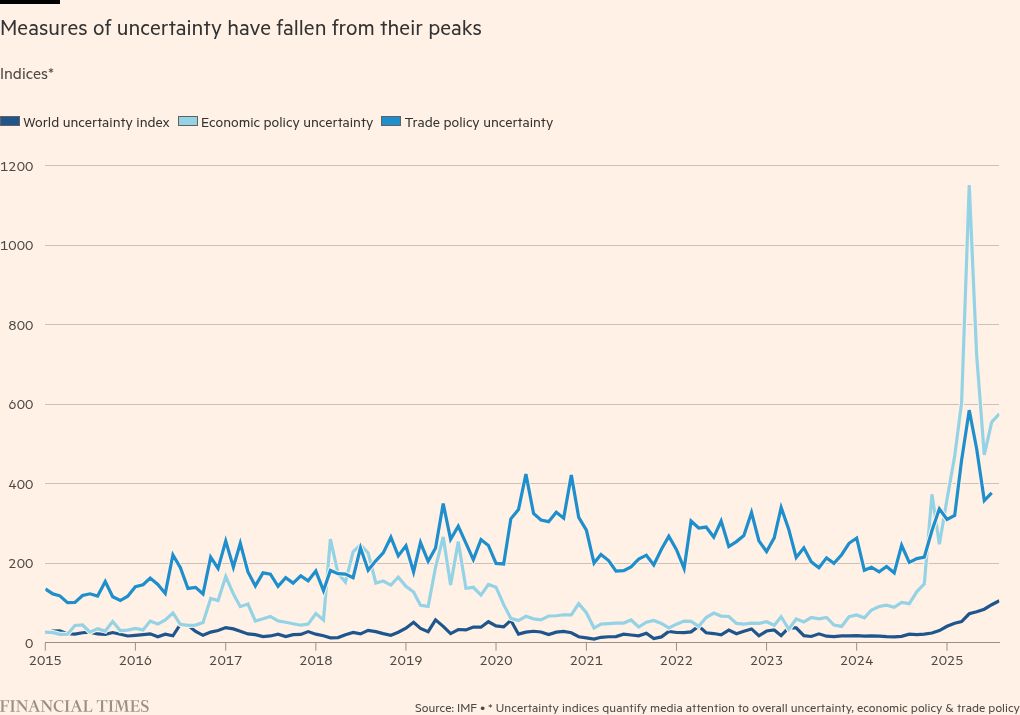

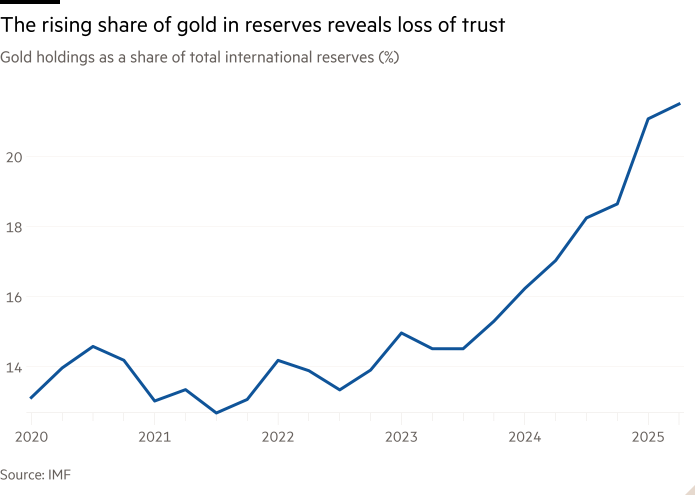

Why has the world economy been relatively robust? Georgieva (and the WEO) offer four explanations: less severe tariff outcomes than feared; private sector adaptability; supportive financial conditions; and improved policy fundamentals. (See charts.)

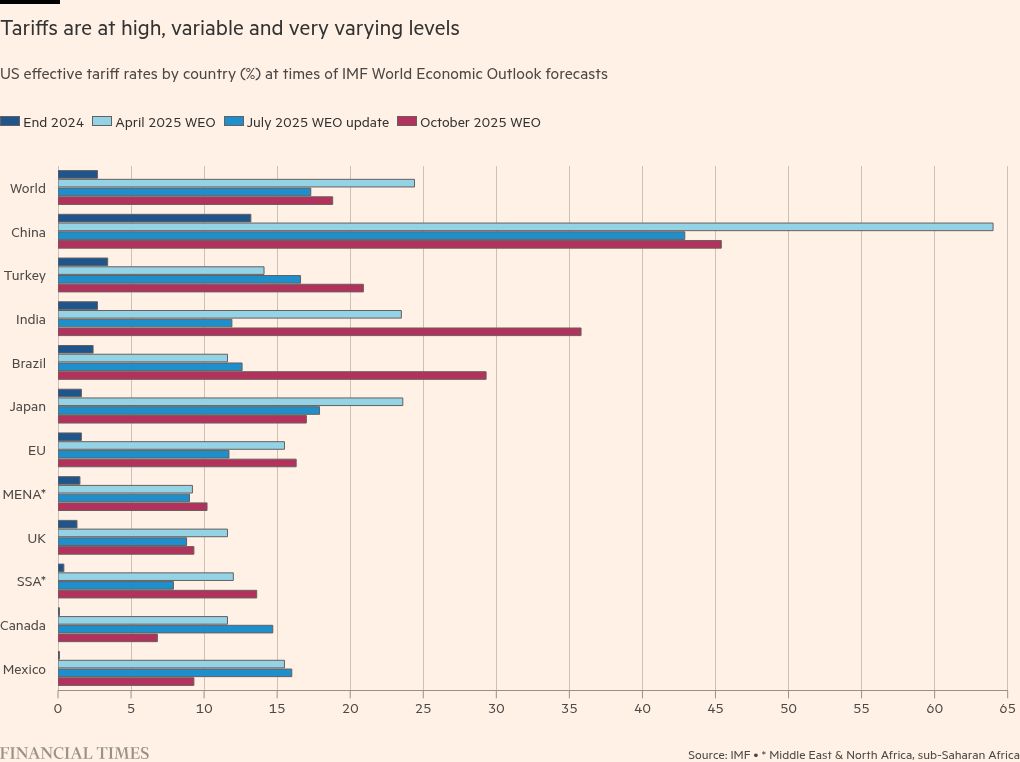

First, it is indeed true that tariffs have ended up somewhat less high than initially indicated on Donald Trump’s “liberation day”, April 2 2025. In the end, argues Georgieva, “the US trade-weighted tariff rate has fallen from 23 per cent in April to 17.5 per cent now”. Moreover, there has been surprisingly little retaliation. Yet these are still high tariffs.

Second, the private sector has responded in a helpful way. This has been especially true in the short run. Thus, notes the WEO, “households and businesses front-loaded their consumption and investment in anticipation of higher tariffs”. Moreover, implementation delays allowed businesses to postpone price changes. In addition, exporters and importers absorbed some of the price increases. Nevertheless, pass-through is occurring. Tariffs are a damaging tax: they will in the end distort the structure and growth of world output.

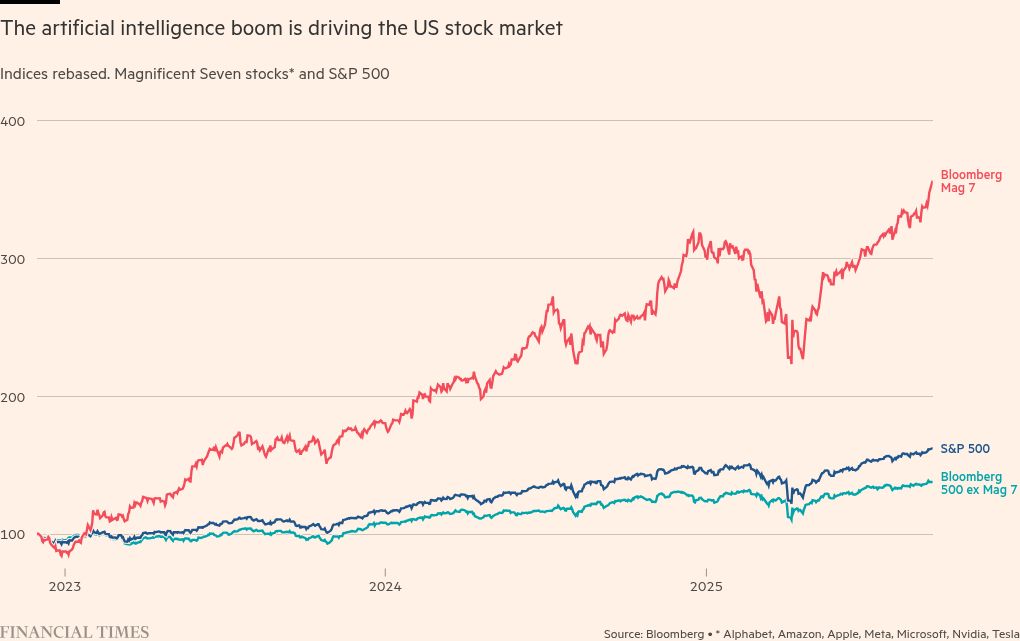

Third, stock markets have continued to be buoyant and financial conditions to remain supportive more broadly. Part of the reason for this, notably in the US, is the AI investment boom. Whether this is rooted in reality or is the sort of bubble that has too often accompanied such innovation is unknown.

The fourth feature seems to be particularly true of emerging economies. Many have learnt from painful past experience and so have pursued more disciplined fiscal and monetary policies than they used to do. That is the theme of chapter two of the WEO. The problem is that external conditions are unlikely to get easier for many of them. China is grappling with US hostility and domestic weaknesses. Brazil and India have been hit by the criminally high US tariffs of 50 per cent. In the case of Brazil, this is largely because, remembering its military dictatorships, its courts have put its would-be dictator, Jair Bolsonaro, in prison for 27 years. Why should Trump detest this so much?

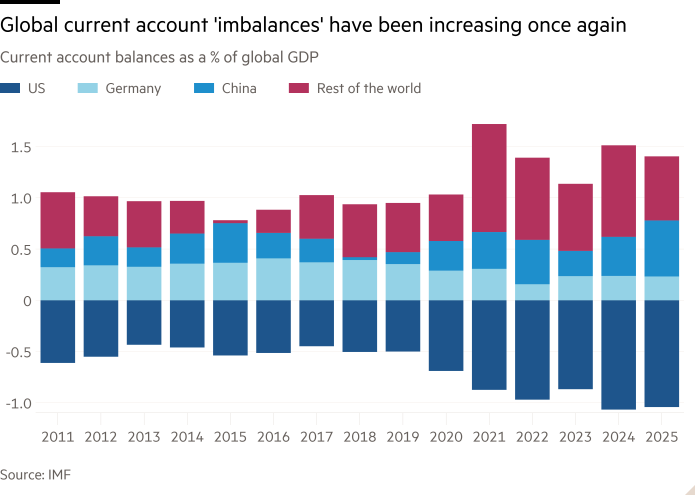

At a time such as this, when the world system is being overturned, it is dangerous to have confidence in what lies ahead. As the IMF notes, there are plenty of fragilities, notably those fiscal deficits and debts. It notes, for example, that the US general government fiscal-balance-to-GDP ratio is expected to deteriorate by 0.5 percentage points in 2026, largely owing to “the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) and despite an offset of about 0.7 percentage point of GDP from projected tariff revenues”. This also makes big reductions in global current account imbalances rather unlikely, though the IMF forecasts modest reductions.

That, in turn, would presage further skirmishes in the global trade war, especially between the US and China. Quite apart from Trump’s tendency to view any bilateral trade surplus as proof that its partner is ripping the US off, China is also viewed as an all-round strategic competitor. The US is particularly upset that China uses its trade muscle in these fights. Scott Bessent, US Treasury secretary, has accused China of trying to hurt the world’s economy after Beijing imposed sweeping export controls on rare earths and critical minerals. So, how does Bessent imagine US victims feel about the trade war being waged upon them?

The meetings of the IMF and the World Bank are an opportunity not only to consider the overall state of the global economy and the salient risks of further disruption, but particularly to focus on the condition of the poorest countries and people. The WEO notes that “the world’s poorest economies, including those suffering from prolonged conflict, are particularly at risk of seeing their growth momentum decelerate”. One of the reasons for this is cuts in grants and concessional lending. The abrupt closure of USAID is likely to be particularly significant for health. A sobering study published in The Lancet concludes that the dismantling of the agency “could result in more than 14mn additional deaths by 2030”.

The IMF and World Bank were created in 1944 to establish the principle of global economic co-operation. The need for this has most certainly not ended. It is encouraging that the US remains a member. The challenges ahead are huge, not least the need to maintain economic progress at a time of such geopolitical upheaval. No country, however powerful, will be immune if the global economic system blows up, instead.