Good morning. Yesterday, in news that rightfully overshadowed the markets, the first stage of the Gaza peace plan commenced. As we’ve said before, this is better news than anything that the markets could possibly produce.

In other good news, the Nobel Prize for economics was awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt for their research on how innovation drives growth. Here’s to hoping their lessons are well-heeded by policymakers. Email us: unhedged@ft.com.

China’s rare earth exports threats

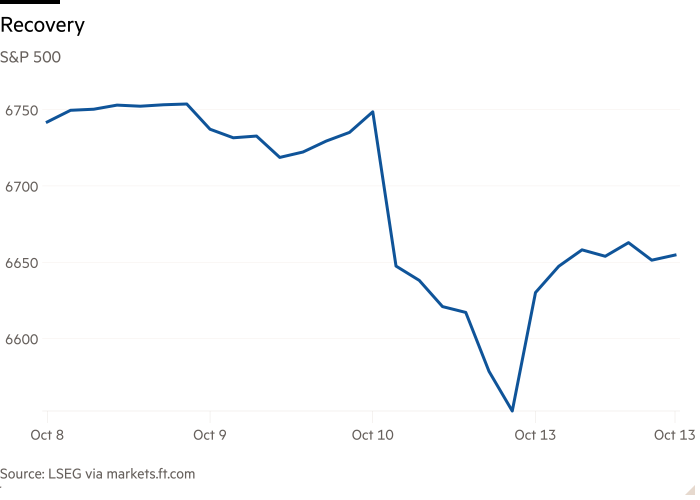

The market calmed down on Monday and managed to recoup more than half its losses from Friday’s sell-off — which all began after President Donald Trump threatened a 100 per cent tariff rate on China to retaliate against its new rare earths export curbs.

China hasn’t backed down much from its original stance — its commerce ministry said it was “not afraid” of a trade war. Meanwhile, the White House has notably softened its rhetoric since Sunday. “The USA wants to help China, not hurt it!!!,” Trump said on Truth Social. Investors appear to have been reassured by the US president’s about-face (and weren’t too surprised by it).

But is it wise of investors to brush off China’s rare earths export threats? In the short term, Beijing’s bark probably won’t amount to much, according to Ed Mills at Raymond James. The rare earths restrictions . . .

. . . should be viewed as China seeking leverage ahead of the October 30-November 1 Apec summit, where Presidents Trump and Xi are set to meet after several months of US-China trade negotiations. China’s previous restrictions on rare earths were a key catalyst for the Trump administration to back off on restricting Nvidia’s H20 and AMD’s MI308 chips . . . While not without escalatory risk, the news could compound existing momentum towards advanced tech restrictions being relaxed.

UBS’s Ulrike Hoffmann-Burchardi agreed:

The history of Trump-Xi negotiations suggests that escalation is often followed by tactical truces, and rare earth minerals versus shipping fees could ultimately seal a deal.

It looks like the latest round of threats are just a step towards a final agreement, not where things will end up — that much the market has picked up on.

However, China’s global rare earths monopoly raises longer-term concerns. It commands the majority of global rare earths production and controls about half of the reserves worldwide. Beyond this, China also has a critical chokepoint in the processing capacity segment of the supply chain. It controls around 90 per cent of refining and separation capacity, as well as permanent magnet manufacturing.

Although rare earths are just a small fraction of costs for producers, a decrease in the availability of inputs can be disruptive across nearly every major US industry: technology, carmakers and defence, among them. “Given the huge administrative burden that these new controls will impose, even if the authorities intend to approve most licences, the logistical challenge involved could lead to delays in approving shipments and so increase the risk of wider dislocation across supply chains,” according to David Oxley at Capital Economics.

China’s dominance in rare earths is not new. The US has taken some measures to reduce its vulnerability. “That said, such steps are likely to take years to significantly reduce dependence on China as a source of rare earths and critical minerals,” said Oxley.

For now, the threat probably won’t amount to much. But it is a reminder of how much is on the line.

(Kim)

Much ado about Mullen

All the fun’s to be had in US car companies these days. The collapse of First Brands and Tricolor continues to dominate attention, but out in California’s Orange County is another car group that’s been sputtering for years.

On Monday, Mullen Automotive — perhaps the greatest American car company you’ve never heard of — was officially delisted from the Nasdaq and began trading on the US’s main over-the-counter exchange. It had been a long time coming.

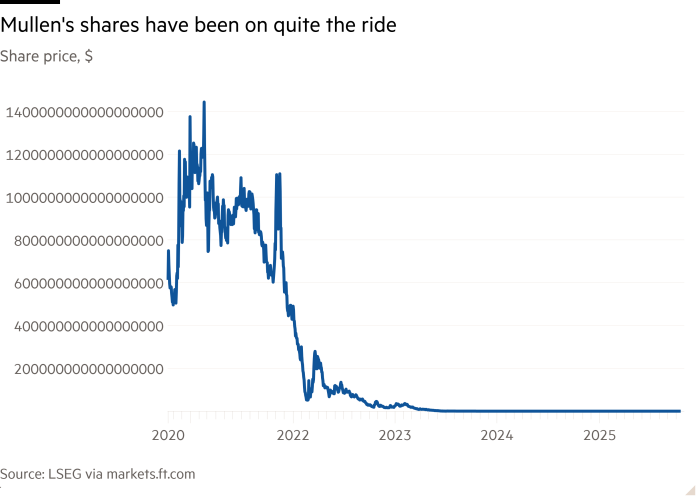

Since 2015, the electric-vehicle manufacturer, which rebranded as Bollinger Innovations in July, has racked up huge losses and received at least eight delisting notices, almost always for failing to maintain a $1 share price for 10 consecutive business days. Until this week, Mullen had Houdini’d its way out of trouble every time, with no less than nine reverse splits to its name since 2021, more than any other Nasdaq stock.

Reverse stock splits — aka stock consolidations — slash the number of circulating shares while proportionally inflating their price. You can see why companies trying to meet minimum bid price requirements might find them appealing.

Prolific reverse splitting can cause fun side effects. Look up Mullen on your nearest Bloomberg terminal, for example, and you’ll notice that its split-adjusted peak share price in 2021 was theoretically (deep breath) one quintillion, four hundred and forty-three quadrillion, six hundred and twenty-eight trillion, eight hundred and five billion, five hundred and seventy-eight million and thirty thousand dollars.

Between the first quarter of 2021 and Q1 2025, Mullen also sold roughly $500mn of convertible notes, common stock and warrants. The trades must have been profitable for the buyers, because filings show the same investors returned again and again whenever Mullen needed cash. The company fell to a net loss of $304mn in the nine months to June, when it began accepting bitcoin and the $Trump memecoin for its commercial EVs.

Mullen’s abnormalities don’t end there. For a brief, wondrous moment in early April, when markets were reeling from Trump’s liberating tariffs, Mullen was America’s second-most actively traded stock behind Nvidia. In 2023, chief executive David Michery was paid a salary of $750,000 plus $48.8mn in stock awards. Median total pay for S&P 500 bosses rose to a meagre $19mn in 2024.

Mullen isn’t in the business of extending subprime loans, like Tricolor, or financed by some of Wall Street’s biggest banks, like First Brands.

But maybe there’s a macro signal in the company’s delisting if you squint. Perhaps Mullen’s investors ran out of funds, or regulators and the exchange — both of which have recently pledged to tighten trading standards for small stocks — quietly let it be known that enough was enough. In a press release, Michery described the move to the OTC Markets as a “logical and financially prudent step”.

Whatever went down, Mullen will be sorely missed.

(Steer)

One good read

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.