Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

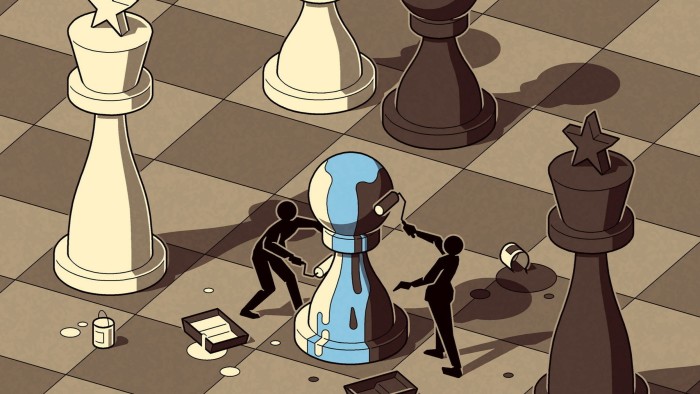

To get a sense of how tricky it is for the US to move from a world of laissez-faire neoliberalism to one in which state control of markets is of much more importance, consider the great power competition going on in Argentina right now.

With the peso in freefall following a corruption scandal in Javier Milei’s government (which is ideologically aligned with Donald Trump’s administration), the US is trying to orchestrate a $20bn bailout for the country, which it hopes will remain a key regional ally. Last Thursday, the US Treasury said it had bought Argentine pesos in a bid to boost the currency.

But China — which has its own $18bn swap line with Argentina — is parachuting in and buying up the country’s cheap soyabeans, using money that previously would have gone to American farmers, in the wake of the US-China trade war.

That’s bad news politically for the White House. Agricultural states tend to be run by Republicans, and farmers are a small but vocal political constituency in the US, as in Europe.

Trump’s trade wars mean that not only has China — the largest global buyer of US farm products — massively cut its purchases, but also that the cost of things like fertiliser and equipment are rising. This has led farmers to complain that Trump is supporting their competitors.

The result is that the administration will probably unveil new support for American farmers in the coming days. Republicans believe subsidies may be as high as $50bn, following the more than $20bn the US government had to pay farmers for the pain they felt after Trump’s first trade war with China in 2018.

Meanwhile, the Argentine bailout probably won’t go through unless the Milei government pays back the money it owes on its Chinese swap line first. While that might be smart US politics, making Congress look as if it is not pouring good money after bad, “it would reduce the effective size of the US support by $5bn and de facto, be a bailout of the People’s Bank of China”, as economist Brad Setser put it on X.

Welcome to the complex and costly world of geoeconomics.

The US now seems to be following a “Donroe doctrine”, a Donald Trumpian version of the 19th-century president James Monroe’s belief that America should stay out of global affairs and just police its own backyard.

This stance was reasserted by Theodore Roosevelt, and later by John F Kennedy during the Cuban missile crisis, before being supplanted in the era of neoliberalism.

Now, Trump’s version of the Monroe Doctrine is very much in evidence, as the administration ends a multiyear “pivot to Asia” with a new mandate to focus on the western and northern hemispheres.

China has been practising its own form of geoeconomics for more than two decades. It has used a long-term lens and a strategic focus that has already resulted in, for instance, the successful ringfencing of rare earth minerals. Exports of these have been tightened amid trade negotiations with the US. Domination of the shipbuilding and maritime industries has been another geoeconomic coup (the Trump administration’s remedies on that under section 301 of the US Trade Act, as well as America’s new maritime strategy, may drop in the next few weeks).

Chinese power isn’t limited to Asia or the surrounding regions. It’s very much evident in the US’s backyard. Beijing has upped investment in Latin America over the past few years, building the largest deep-water port on the region’s Pacific coast in Peru, for example, as well as investing in raw minerals refining throughout the region.

The fact that the Chinese can in short order switch soyabean purchasing from the US to Argentina is, as competition policy expert Matt Stoller wrote recently on his Substack, “a stunning show of power and discipline, and something Americans have a tough time seeing as such”.

I suspect the US administration does grasp this, which is why it is so focused on the bailout, as well as on other things like new alliances in the maritime sector. Last week, the US finally signed a memorandum of understanding with Finland to build a whopping 11 new icebreakers, four of which will be constructed in Finland and seven in America, as part of an effort to increase its maritime presence in the Arctic.

“This was very much driven by Trump himself,” said Finland’s President Alexander Stubb, with whom I spoke right after the memorandum was signed. “The Arctic is key [for Trump], economically and strategically,” Stubb says.

New ships, the first of which will be built by 2028, will help assert US presence amid a new geostrategic competition in the High North. At the end of September, Norad (the Canadian-American command responsible for policing North American airspace) intercepted Russian aircraft in Alaskan airspace. That underscores the increased Russian and Chinese presence in the Arctic, as maritime commerce, security operations and a race for natural resources in the area intensify.

So much for a pre-emptive Donroe doctrine. The truth is that China and its allies are already in America’s backyard and, to keep it safe, the US will have to work with and support its allies. As everything from shipbuilding to the soyabean wars shows us, there is no going it alone, even in a more mercantilist era.