Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

Donald Trump’s second term is transforming the world. It is quite likely that the autocratic regime he and his minions in the administration and the Supreme Court are creating will endure. Yet even if it does not, it will have changed the world simply because it has happened. What has happened once can happen again. This must transform views of the future. Yet that future will not just be determined by the US. China is also a superpower. So, what role might it play in this new era?

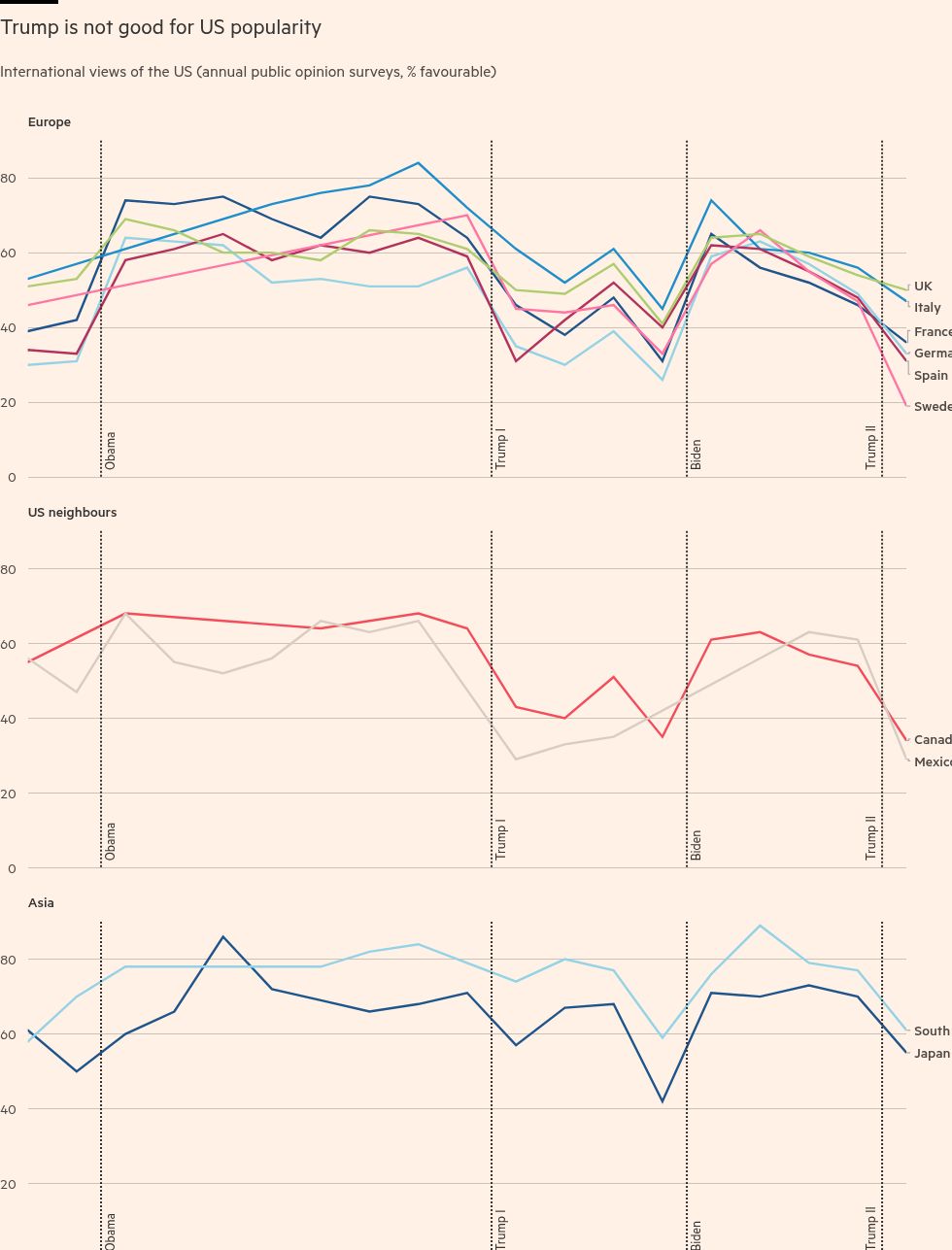

Let us start with the US. Other democracies used to think it shared core values with them. But this US quite clearly does not. Trump himself is grievance-fuelled, deal-driven and capricious. This alone makes it hard to deal with him. As Célia Belin of the European Council on Foreign Relations adds, his foreign policy “is his domestic agenda, exported”. Thus, she writes, “Trump and his Maga camp are using the same three methods at home and abroad: elimination, transformation and subjugation.” At home, they seek to eliminate the “deep state”, and turn a liberal America into a nationalist one. Abroad, similarly, they seek to eliminate alliances and other commitments and transform allies into vassals.

These goals are bad for most of the world and foolish for the US. Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics takes this long view in a Foreign Affairs article on “The New Economic Geography”. In the post-second-world-war world, he writes, the US provided insurance to other countries against all sorts of risks. But the costs it bore were not uncompensated: other countries invested in the US, opened their economies to US investors, lent money to the US cheaply, made the US dollar the global currency, and turned US capital markets into the hub of global finance. This was then a mutually beneficial deal.

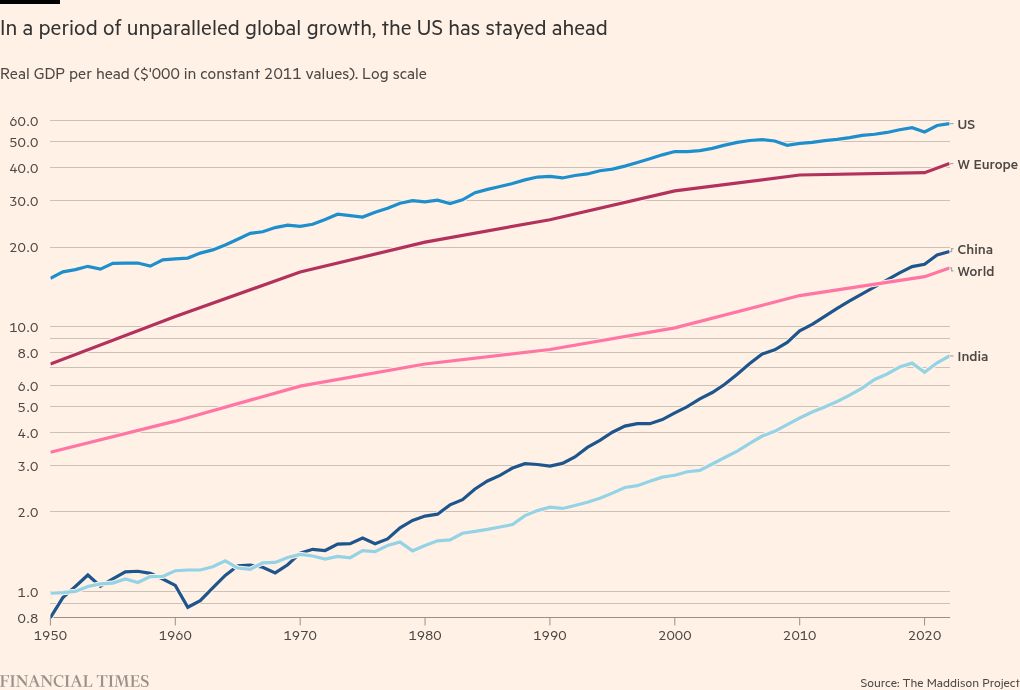

Trump whines that the US has been “ripped off”. The fact, however, is that it has remained the world’s richest and most technologically advanced economy in a period of unparalleled global growth: between 1950 and 2020 average global real GDP per head rose by 360 per cent! Ripped off? Hardly.

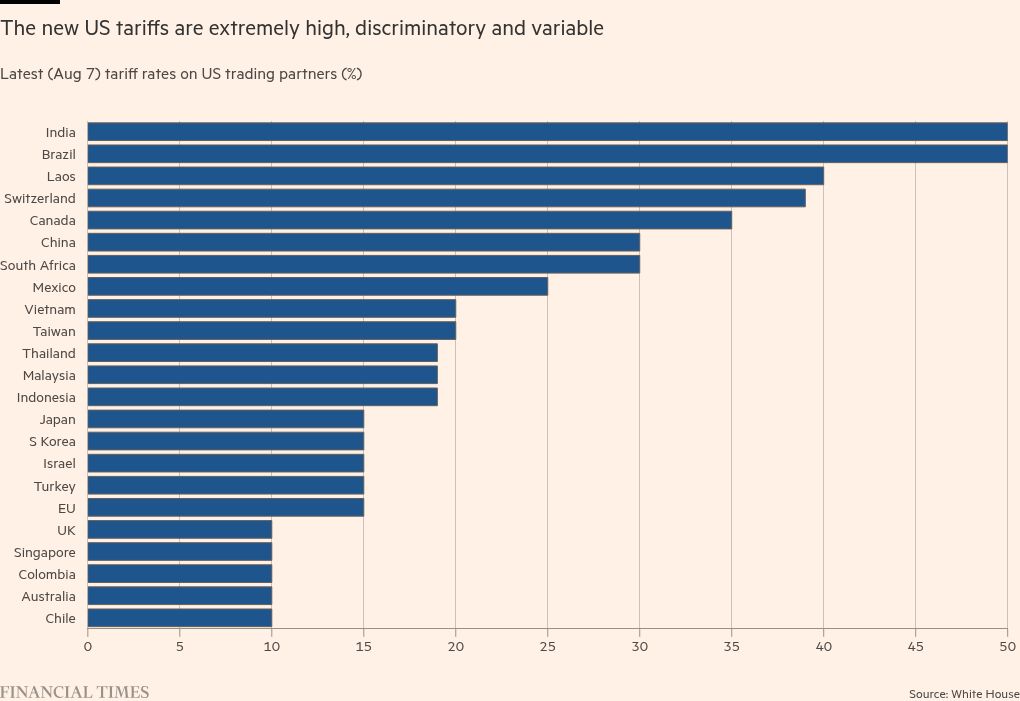

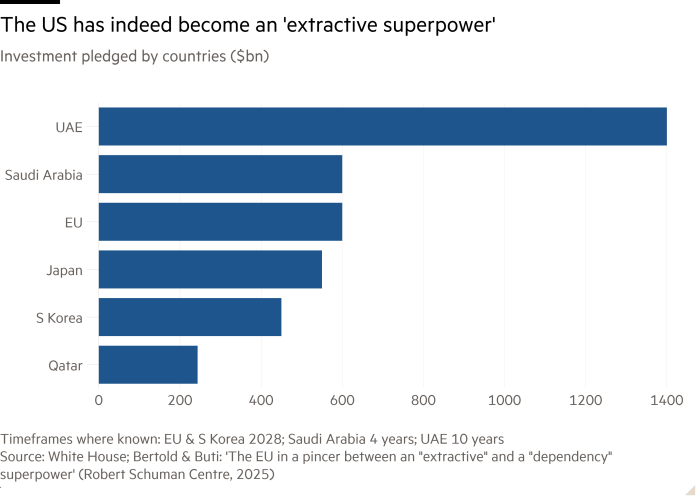

Alas, Trump has killed this grand bargain. In its place, we see a host of unreliable and predatory deals. In addition to imposing huge tariffs on countries that thought they were friends of America, Trump has demanded money be invested at his own discretion, to the great irritation of foreign partners. This is pure gangsterism.

Another way of thinking about what has happened is that in the old world of trust in the US, there was interdependence, but some countries were more dependent than others. This allowed interdependence to be “weaponised”. As Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman argue, the US did so, rather freely. Within what were seen as mutually favourable long-term relationships, such weaponisation, notably over the use of sanctions, was tolerated, however grudgingly. But Trump is turning interdependence into a chokehold. That is a very different matter.

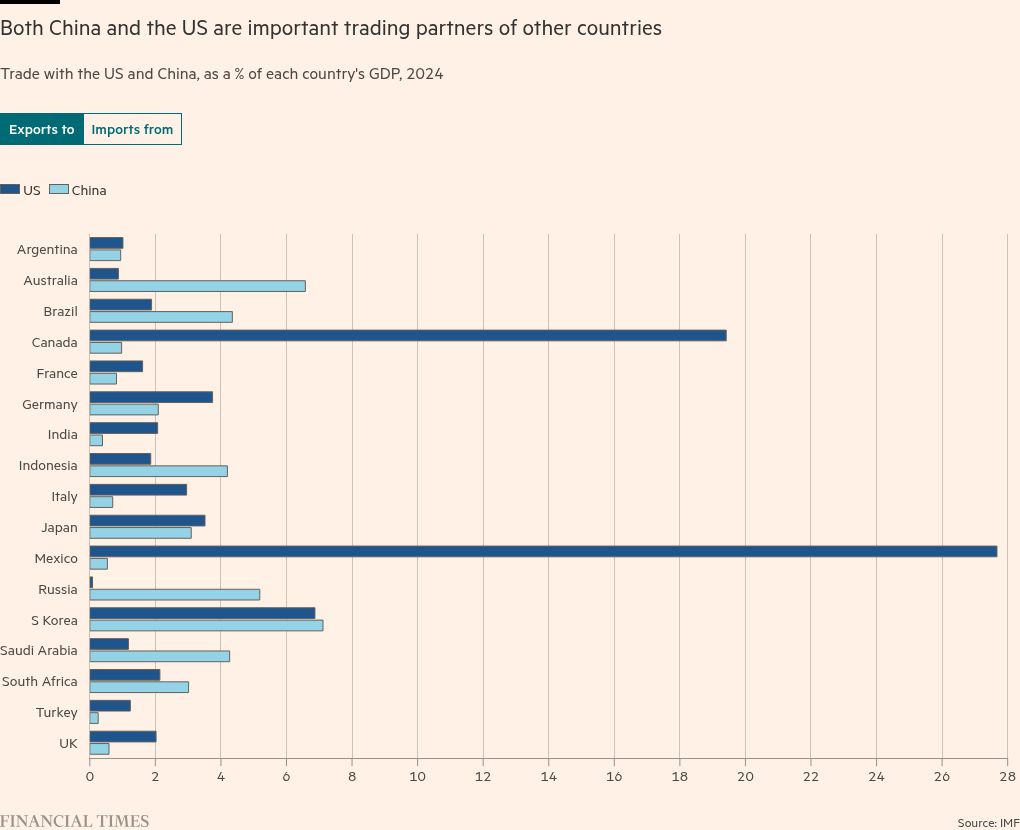

Moreover, others can play at this game. Indeed, China already is. This idea is presented in a stark way by two European economists, Moreno Bertoldi and Marco Buti, in a paper that considers how the EU is caught in a pincer between an “extractive” and a “dependency” superpower”. China is the latter: it creates dependency. By flooding markets with its goods, it exacerbates global trade and macroeconomic imbalances. Its exploitation of WTO rules in support of infant industries undermines confidence in the rule-based trading system it allegedly supports. Its weaponisation of critical materials and control of the clean-energy supply chain is also weakening support for policies aimed at tackling climate change, notably in the EU. Yet China is a more reliable and rational partner than today’s US: at least, it does not deny climate realities.

It is impossible for the rest of the world to ignore these predatory superpowers, since together they generate 43 per cent of global GDP at market prices (and 34 per cent at purchasing power parity). But some way does need to be found to manage their global impact.

A part of the response must be hedging. The US should be the main victim of this, since it has had far and away the most valuable alliances. But a regime that happily destroys its principal national assets — its great universities, its scientific pre-eminence, its openness to brilliant immigrants and even the rule of law — will not worry about that.

Moreover, Trump believes allies can be turned into vassals. This is not inconsistent with their behaviour. The UK has chosen to be a vassal. That, ironically, is a consequence of Brexit’s search for enhanced national sovereignty. But Japan, South Korea and even the EU do not look all that different, so far.

Yet this is, I hope, unlikely to last. Both former allies and other countries will look for alternatives. This will increase China’s influence. Indeed, the US has already pushed India and Brazil closer to Beijing: Xi Jinping must quietly thank Trump for his egregious blunders each day. In all probability, then, countries will try to play one superpower off against the other. India and Brazil will behave in this way, as will others.

Vassalage and pitting one superpower against another leaves a third option. The world we are moving into is going to be poorer, more unstable and more dangerous than the one we had before the US embraced Maga. Other countries should dare to pursue a more independent course, together, including on managing global public goods, such as health, climate, even security. Could the EU help lead the way on this? This may now seem a fantasy. But stranger things have happened.