Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the centre of a maximum-security storage facility sits one of the world’s biggest vaults for precious metals, emblematic both of Asian ambition to become the centre of the global gold trade and the difficulties in achieving that goal.

As gold prices rocket to record levels, the company behind The Reserve in Singapore wants to lease space to private banks and family offices, allowing them to store their ultra-wealthy clients’ gold and silver bullion in a secure facility only minutes from south-east Asia’s busiest airport.

But while The Reserve, which opened last year, is designed to store 10,000 tonnes of silver and 500 tonnes of gold, it currently holds just a fraction of that capacity.

“London took 200 years to build the infrastructure to become the centre of the world gold market,” said Albert Cheng, chief executive of the Singapore Bullion Market Association. “We have lots of work to do, but it won’t take us that long.”

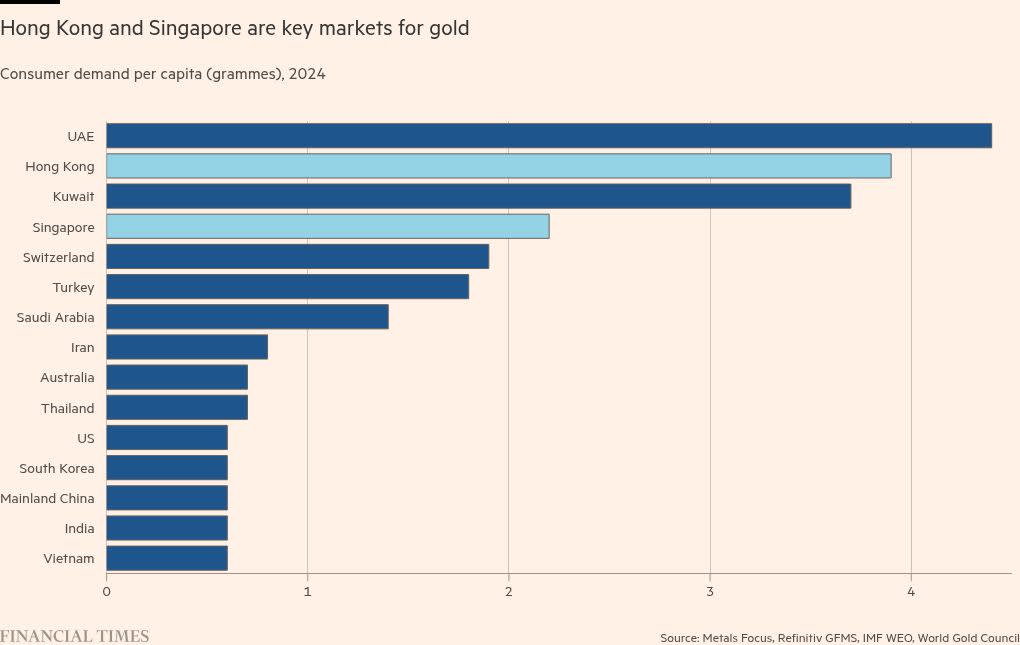

As geopolitical instability pushes gold prices higher, Singapore and Hong Kong, two of the world’s biggest consumer markets per capita, are trying to shake up a business that for decades has centred on bullion being stored, refined and traded in London, New York and Switzerland.

The Reserve and similar facilities under development in Hong Kong underline these efforts. The city state and the Chinese territory have also launched gold futures contracts this summer and expanded bullion warehousing and refining capabilities.

“The centre of gold trading is increasingly moving east,” said David Greely, chief economist at Abaxx Exchange, a Singapore-based bourse, which launched a gold contract earlier this year. “There is a big untapped demand for an Asian trading hub.”

Recent confusion over US tariffs on gold has created fresh demand for regional hubs, some analysts say. In August, US customs said tariffs would apply to gold bars, shocking the bullion market, but the policy was reversed by President Donald Trump a few days later.

“There is a window for these hubs to explore ramping up their product availability,” said Nicky Shiels, head of research at MKS Pamp, a Swiss refinery, which recently set up its regional headquarters in Hong Kong.

While Singapore’s ambitions to establish itself as a global gold hub have been in the works for more than a decade, Hong Kong has stepped up its efforts in recent months.

In his annual policy address on September 17, city leader John Lee said Hong Kong would increase its gold storage capacity to more than 2,000 tonnes in three years, with a view to creating what he called a “regional gold reserve hub”. It currently has more than 200 tonnes of capacity.

Hong Kong’s proximity to mainland China, which is the biggest consumer and producer of gold, make it a natural hub for the bullion trade. The Shanghai Gold Exchange is using Hong Kong to promote its renminbi-denominated gold contract to international investors.

In June, SGE opened its first offshore vault in Hong Kong and launched two renminbi-denominated gold contracts there. The depth and liquidity of the gold market can make it hard for new contracts, regardless of jurisdiction, to break through.

Several international refineries have established a footprint in Hong Kong, including Heraeus and Metalor, while MKS Pamp participated in the launch of the SGE’s new contracts.

However, some traders are concerned about the risk of political interference. “There is always this fear — is it a true international market, or is it something where, if the Chinese government didn’t like the result, they could change the rules?” said Robert Gottlieb, a former top gold trader at JPMorgan and HSBC.

Singapore’s political neutrality is why BullionVault chose the city state over Hong Kong, said Adrian Ash, the gold trading platform’s head of research.

The gold markets in Hong Kong and Singapore both had work to do on improving liquidity, storage, custody and settlement services to compete with the developed centres, said Gregor Gregersen, founder of Silver Bullion, the company behind The Reserve. “What really matters in this industry is building up liquidity,” he said.

Hong Kong has a long way to go to catch up with Singapore when it comes to its warehouse facilities. The 30,000 sq m maximum security Le Freeport was opened in 2010 and became known as “Singapore’s Fort Knox”. Originally opened to house fine art, it has since been used to safeguard luxury cars, wine, jewellery and precious metals. Specialist gold storage companies such as Brink’s and Loomis use the facility.

“On the vaulting side, we are ahead in Singapore; on trading, I would say Hong Kong is ahead,” said Gregersen.

“Both hubs have realised that the world is changing and they need to revisit their role when it comes to gold.”