Overseas sales of the US’s top farm export have plummeted as China shuns American soyabeans in a “devastating” blow to the country’s farmers.

The new export season for soyabeans has opened with no sales or shipments to China, government data shows — a sharp break from a year ago, when it had already booked 6.5mn tons. Meanwhile, inventories have begun to pile up with the onset of the fall US harvest season.

For decades, more than half of all US soyabeans went to China, the world’s biggest buyer. But this year, as trade talks between Washington and Beijing stall, not a single American soyabean has headed east, leaving farmers struggling to stay afloat as bins fill and prices sag while China turns to record supplies from Brazil.

“We’re up against the clock right now,” says Darin Johnson, president of the Minnesota Soybean Growers Association and a fourth generation farmer. “Even if we do come to terms on an agreement [with China], it’s just not going to be in time for this harvest.”

Like soyabean farmers across the US, Johnson is staring down a harvest with nowhere to go. Growers are facing “a glut of soyabeans”, he says, the impact of which could be “devastating”.

Soyabeans are primarily used as livestock feed, and also have applications in industrial and consumer manufacturing. Byproducts like soyabean oil can be used to create products from biofuels to firefighting foam.

The oversupply is driving down prices at a time when the cost of inputs such as fertiliser is also rising due to tariffs.

Since the administration of President Donald Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese goods, Beijing has retaliated by halting all purchases of American soyabeans. The move threatens growers across the Midwest with steep losses and could imperil farms that have been in families for generations.

Beyond the economic toll, the disruption carries political weight: soyabean farmers are a key voting bloc, turning the trade dispute into a flashpoint with national implications.

Trump said on Thursday he will use tariff revenue to fund a programme to support US farmers, echoing comments made by agriculture secretary Brooke Rollins to the Financial Times last week.

“We’re going to take some of that tariff money that we made, we’re going to give it to our farmers, who are, for a little while, going to be hurt until the tariffs kick in to their benefit,” Trump told reporters at a signing ceremony in the Oval Office.

In the meantime the crisis hitting farmers risks spiralling.

“When the ag economy is not doing well, that’s a direct impact to our small rural communities,” said Johnson. “It directly impacts rural America, it impacts the little town that I live in.”

American growers have been here before.

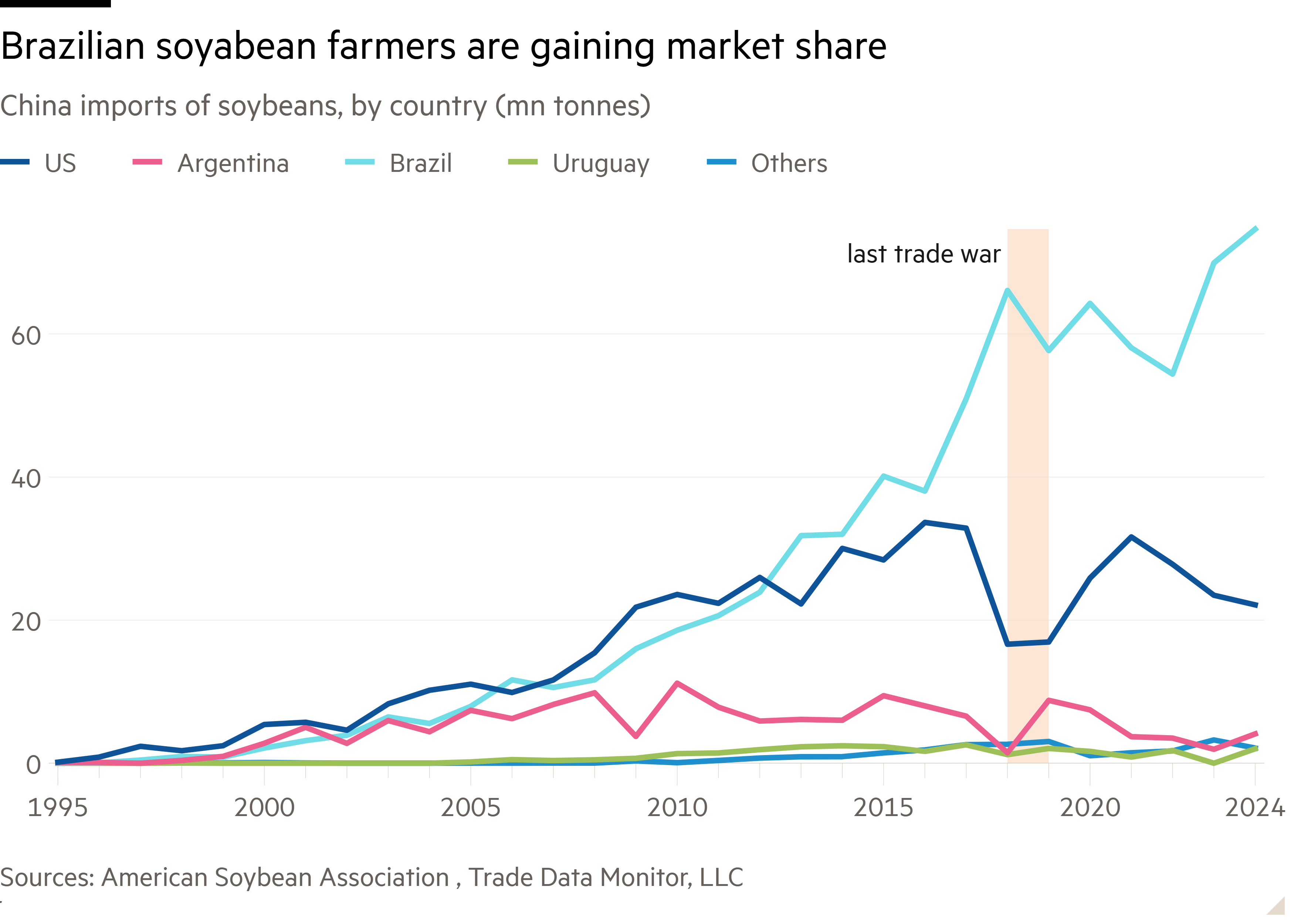

In 2019, after Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese goods, Beijing slashed soyabean imports from the US. The Trump administration launched a $23bn bailout for farmers. In that round, Brazilian farmers were the ultimate beneficiaries.

“The last time [the US] did this, we lost about 20 per cent market share to Brazil, and that never came back,” said Todd Main of the Illinois Soybean Association.

This time around, Chinese buyers have again turned almost entirely to South America, pushing Brazilian soyabean exports to record highs. Between January and August, Brazil shipped 66mn tonnes to China — three-quarters of its total exports, government data show.

Raphael Bulascoschi, analyst at commodities brokerage StoneX, said: “The effects of China’s boycott of US soyabeans have been highly favourable for Brazilian producers.”

The administration has also dismantled the US Agency for International Development (USAID), which used to purchase “a lot of surplus agricultural commodities for distribution around the world”, Main said.

In addition to using tariff revenues to support farmers, the administration has also proposed increasing blending quotas for biofuels, which would bolster domestic demand for soyabeans.

While a federal bailout helps in the short run, “it doesn’t help with the permanent loss of market share from expansion in other parts of the world”, said Scott Gerlt, chief economist for the American Soybean Association. Similarly, biofuel blending levels “will not come close to offsetting the export demand”, he said.

“There’s a lot of financial distress out there and the longer China stays off the market, the more that distress is going to grow,” he said, adding that farm bankruptcy numbers were already increasing.

The loyalty of farming communities to Trump also hangs in the balance.

Farmers want free trade too, Johnson said. “We completely understand that trade deals haven’t been perfect and they need to be negotiated,” he said. “[But] this situation could get pretty dire in a real quick hurry.”