The writer is research associate at Oxford university’s China Centre and at Soas and an adviser to the China Observatory, Council on Geostrategy. He is a former chief economist at UBS.

China’s industrial policy is not well understood. The fiscal price tag, highlighted in the latest IMF report that Alphaville covered on Tuesday, is eye-poppingly large at around 4.4 per cent of GDP. And the Fund reckons it costs the country a further 2 per cent points of GDP each year in lost productivity.

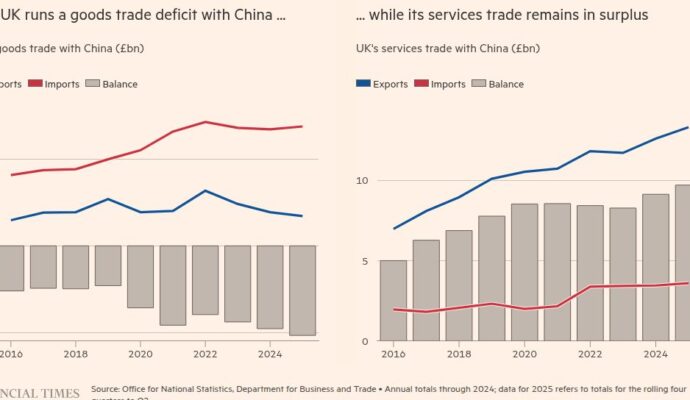

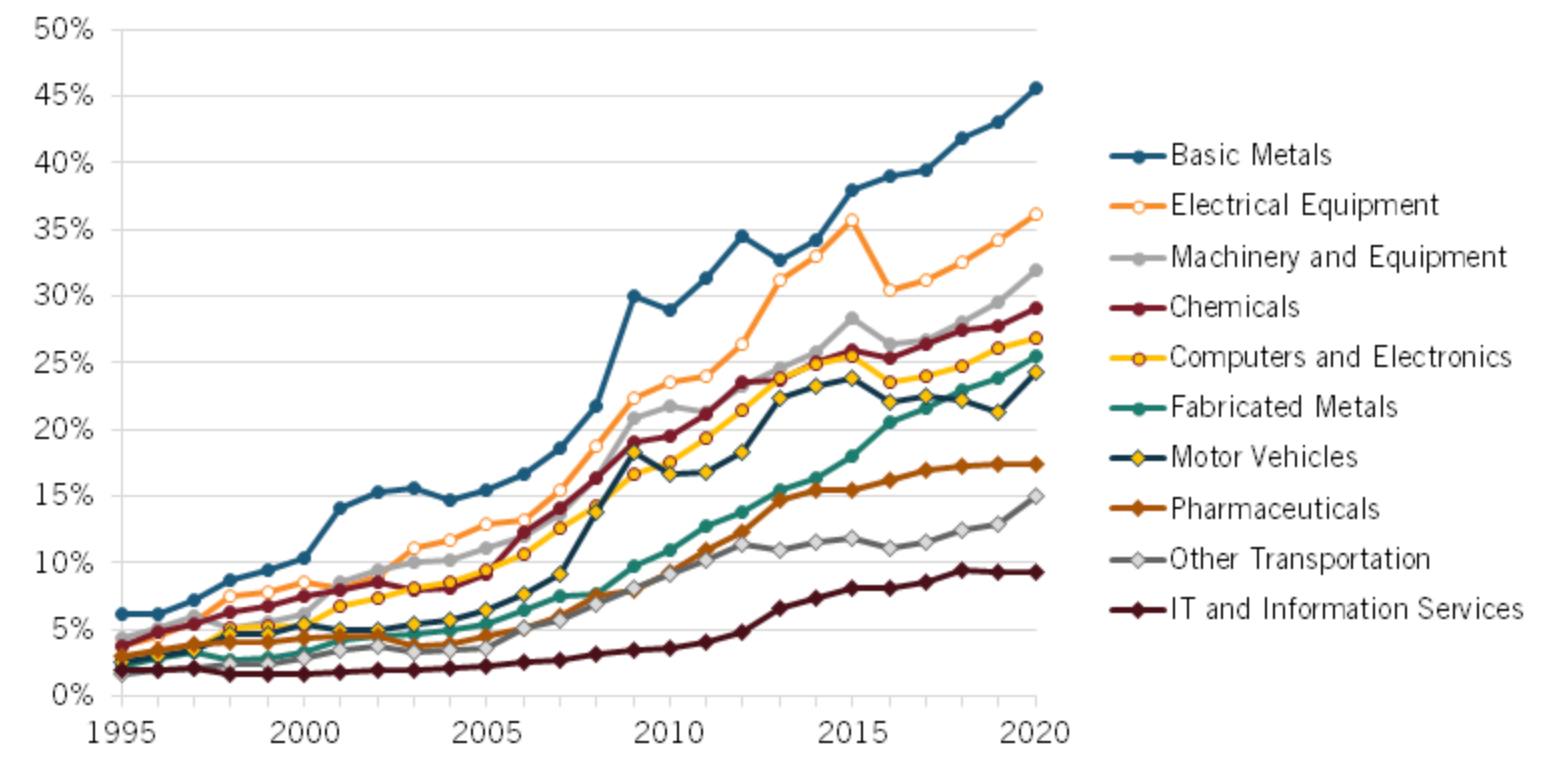

The impact of Chinese industrial policy on the world economy is so large that Donald Trump’s tariffs are, by comparison, a minor nuisance. America’s roughly 8 per cent share of world imports is less than half of China’s share of world exports. And the industrial policy-export nexus is not only aggravating China’s own domestic systemic problems, but becoming increasingly problematic for a growing number of countries.

The economist Barry Naughton, renowned guru of Chinese industrial policy, has described China as being engaged in ‘the greatest single commitment of government resources to an industrial policy objective in history.’ Other estimates as to the measurable cost of Chinese industrial policy have been made by the OECD, the CSIS, and the Kiel Institute. Ballpark — these come to around 1.5-2 per cent of GDP, or 4-5 times that of large OECD countries.

The IMF report has more than doubled this, but even so there is much that is hard to quantify, and more that is impossible to get a handle on. These include:

the government industrial guidance funds — essentially public-private venture capital funds, designed to raise capital for innovation, industrial transformation, and local economic growth with a target of 11 trillion RMB;

local government subsidies, which can be larger than national subsidies, especially where land purchase is concerned;

financial largesse in the form of ubiquitous implicit guarantees and below-market credit and financing rates;

below market input prices for energy and land;

the subsidisation of supply chain firms, and;

regulatory, procurement, and market access favours to preferred companies.

And that’s before we count benefits to firms from tariff protection, an undervalued Renminbi, and the use of ‘golden shares’ by the state.

If the IMF reckons 4.4 per cent of GDP is a base, it’s not hard to get a more holistic price tag up to at least 5, maybe 7-8 per cent of GDP, and possibly even more. Everyone can get the message: the CCP is deadly serious about this, and it’s important to understand why.

Firstly, China pursues industrial policy for commercial reasons. But it also craves self reliance in key technologies and resilient supply chains, and thinks national security is a big deal. More specifically, it desperately needs something to pick up the slack from the structural funk in real estate and overbuilding of uncommercial infrastructure, absent a marked shift towards a more consumption-driven growth model.

But China’s industrial policy only makes sense if one also acknowledges its geopolitics too. Not to mince words, China’s industrial policy is a state-backed effort to knock the United States off the perch of global technological leadership. Having missed out on the mechanisation, electrification and information revolutions, as the CCP narrative has it, China — following Marxist doctrine about the role of ‘productive forces’ — must now try to dominate the fourth industrial revolution. And this means new technologies including AI, big data, quantum computing and biotechnology. Unlike other nations that have used industrial policy to catch their rivals, China wants to leapfrog them.

Or as Xi has himself said:

‘The next decade will be a critical one. A new round of technological revolution . . . is gathering strength. [It] will bring earth-shaking changes while offering an important opportunity to promote leapfrog development’.

Fine. It’s easy to be wowed, and if you look at how China has come to dominate important sectors already, it is easy to assume history has already been written. But not so fast.

The much lauded EV sector epitomises the problem. A bright light shines on about 10 super successful and profitable firms, but a dark shadow hangs over the other 150 or so, mired in losses, waste, and corruption. The industry is suffering chronic overcapacity and deflation. But so are many others, including lithium batteries, photovoltaic cells, wind turbines, building materials, metals processing, digital finance, semiconductors, standard medical devices and pharmaceuticals. Not to mention real estate and infrastructure. This is a systemic issue, not a random or cyclical problem that can be tweaked.

Cue ‘involution competition’, a phrase invoked by Xi earlier this year to describe the dire state of destructive competition and price cutting that arises from excess production and anti-competitive business practices and leads to deflation. It is clear the government wants to put a stop to it. But this is easier said than done, because the cause of the problem is the government itself. It channels investment and funding into firms and industries on a huge scale, creates incentives to conform rather than compete, and sets unrealistically high economic growth targets for an investment- and export-led economy.

It can’t really shut down the overcapacity problem. It can only decide where it shows up next.

Pressure on China is also very likely to build abroad too. Developed markets are already resisting, but the interesting new development is the raft of trade defence measures being put in place by emerging and middle income countries, for whom China is a large or even the largest trade partner. These include Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, India, South Africa, Vietnam and Thailand. Several now fear premature deindustrialisation as Chinese imports threaten — for example — steel, textiles, and autos.

The consequences of China’s industrial policy then are equivocal, much as they were for Japan. The Japanese experience showed how an economy can boast world class firms, striking innovation, and large mercantilist surpluses, and yet also feature systemic imbalances, political and institutional rigidity, and overcapacity. Great firms and a strong vertically-driven industrial policy do not protect a country from bad macroeconomic outcomes. And the more China doubles down on the former, the bigger the macro risks will become.

Will the government really cut off its own nose? Don’t bet on it.