Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

China’s waste-energy plants are running out of rubbish to burn, as slowing consumption, a declining population and improved rubbish management leave power operators facing shortages.

China poured investment in a huge network of waste-burning plants a decade ago to tackle the “rubbish sieges” plaguing its cities.

The country now has more than 1,000 waste-incinerating power stations, representing more than half the world’s waste power capacity, according to the Global Waste-to-Energy Research and Technology Council.

“In order to solve the problem of rubbish sieges following China’s rapid urbanisation, incineration was a relatively quick [solution],” said Zhang Jingning, secretary-general of the Wuhu Ecology Center, an Anhui-based environmental group that tracks the sector. “Sorting waste can take a longer time, whereas in China, building an incineration plant can take less than two years.”

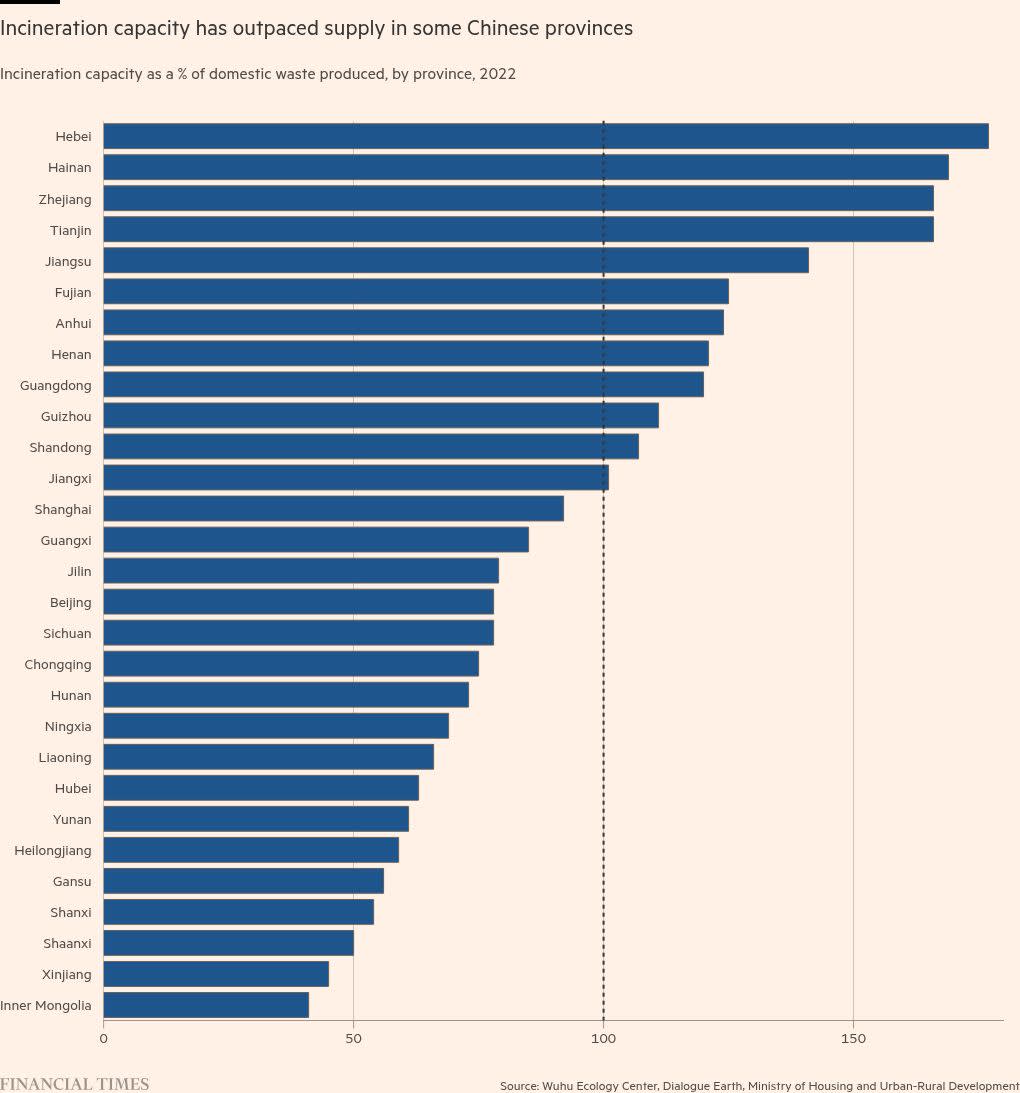

The sector had capacity for about 333mn tonnes of waste in 2022, the most recent year for which complete data was available, outpacing the 311mn tonnes of domestic waste collected that year, according to the most figures from Wuhu Ecology.

It has only continued to grow: China’s plants are now capable of burning more than 1.1mn tonnes of trash a day, far exceeding government targets.

That has left a growing number of operators dealing with overcapacity, according to think-tank data, analyst research and five plant operators who spoke to the Financial Times.

Two plants said some of their incinerators were idle most or all of the year, and two others said they had begun sourcing industrial waste from construction sites or trash from local governments.

“The reduction in waste has an impact on profitability,” said a representative from a plant in China’s central Anhui province.

Some operators have been left in need of trash to burn, resorting to paying hefty fees to property management companies or even excavating landfills, according to reports by local media.

“We have three incinerators, but one is shut down year-round due to an insufficient waste supply,” said a representative from a waste-to-energy plant in Shijiazhuang, Hebei. The plant has capacity to handle about 330,000 tonnes of trash a year, but was burning only about 290,000 tonnes, they said.

The representative attributed the shortage to China’s shrinking population and economic slowdown.

With population decline, “naturally waste volumes decrease”, they said. “We were already earning very little, but now we’re running at a loss year after year.”

Experts have raised concerns about the health and environmental effects of the plants, which produce carcinogenic fumes, leachates that can leak heavy metals into nearby ecosystems and fly ash, which can be repurposed, chiefly for use in building materials, though demand has dropped precipitously amid a years-long property sector crisis

Analysts said China had significantly reduced the level of harmful emissions from the plants in recent years, and noted that waste-burning plants helped reduce overall greenhouse gases by curtailing methane given off by landfills.

China’s environment ministry said the country’s 1,033 waste-to-energy plants generated 13mn tonnes of fly ash in 2024 and 63mn tonnes of leachates the year before, and that annual volumes of both had risen since 2020. About 15 per cent of the fly ash generated was repurposed.

“The number and scale of waste-to-energy plants have essentially peaked, and the pace of new development has slowed significantly,” the ministry said. “Looking ahead, China will continue improving fly ash and leachate treatment.”

Some plants said the declining volume of waste — which is partly the result of stricter rules on domestic waste sorting instituted in 2017 — meant that China’s fight against rubbish sieges was nearly won.

Shenzhen, a city of 18mn in China’s southern manufacturing heartlands, no longer sends household waste to landfills, said Chen Lei, chief guide at the Nanshan Energy Ecological Park, one of five such facilities in the city that together have a daily capacity for 20,000 tonnes of waste, according to the municipal government.

“Having less waste is actually a good thing,” said a representative for a plant in eastern Zhejiang province. “It means the environment is improving.”