Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Chinese economics student Vanora Li was at Columbia’s Barnard College, she toyed with the idea of further study in the US but eventually decided to continue her education at the University of Hong Kong.

“The perceived value of [a] master’s degree [in the US] has decreased in recent years,” the 23-year-old said of her decision. US-China tensions might make US graduates less appealing for Chinese corporations, she said, adding that the job market in the US is “not that friendly to international students”.

Hong Kong’s universities have for decades been an “east meets west” hub for western and Chinese scholars keen to pursue their academic goals in research areas related to China and Asia.

Li and others’ choice of HKU illustrates the resilience of a 114-year-old institution that many doubted would sustain its reputation in the wake of protests in the Chinese territory in 2019 and a broader crackdown.

A sweeping national security law imposed by Beijing on Hong Kong in 2020 limited free speech and prompted the departure of some academics. HKU’s decision to remove the ‘Pillar of Shame’ sculpture commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre outraged scholars and students.

Academic freedom has shrunk, many say. Several of its academics have been attacked by Chinese state-backed media outlets in Hong Kong. US human rights law academic Ryan Thoreson, who was hired by HKU, was denied a visa in 2022.

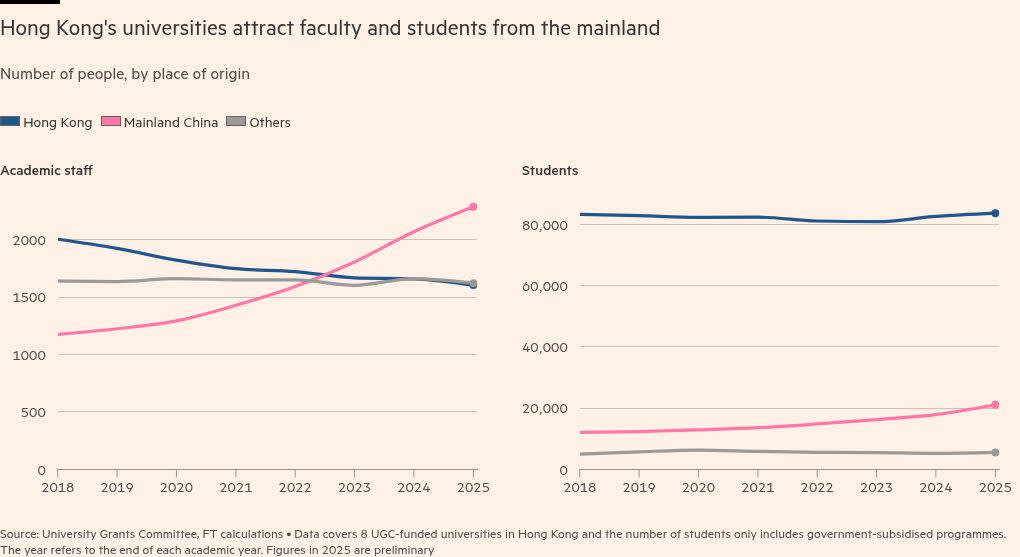

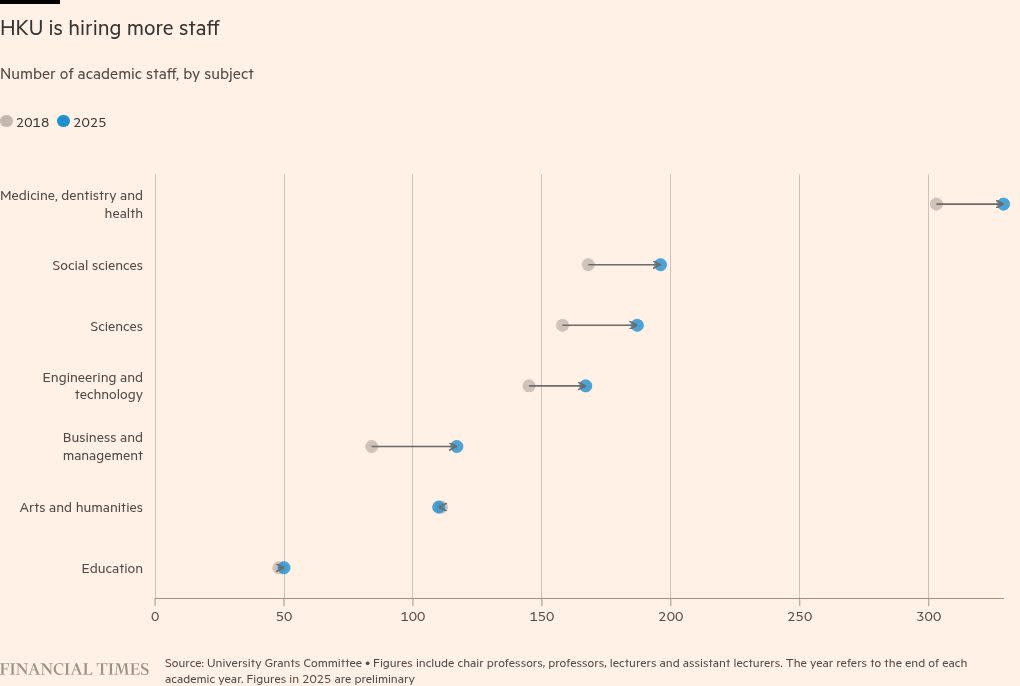

But the number of academic staff at HKU up 13 per cent from 2018, according to data from the University Grants Committee. More than one-third of HKU’s academic staff are now from mainland China, up from roughly 22 per cent in 2018.

The number of academic staff in the business department has risen from 84 in 2018 to 117 this year, UGC said. The number of academics in the medicine, dentistry, engineering and technology departments has also risen. Academics from Europe and the Americas have joined HKU, the university said, though it did not offer a breakdown.

The total number of students at HKU, meanwhile, has increased from 29,099 in 2018 to 42,330 in 2025, with the proportion of mainland Chinese students studying under government-funded programmes rising from about 15 per cent to 24 per cent during the period.

Many mainland Chinese people who studied abroad come “to HKU for [its] western education,” said a HKU social sciences lecturer. “They don’t want us to tell them [the] Chinese party line or propaganda . . . [in that sense HKU] maintains a competitive edge.”

In a move hailed by HKU’s senior management, the university was also this year ranked 11 in QS’s World University Rankings, up from 17 the previous year. That is higher than Yale’s 21 and Princeton’s 25. Elite Chinese universities Peking’s and Tsinghua were ranked 14 and 17 respectively. Some academics question the validity of such rankings which QS says are based on metrics including citations per faculty, academic reputation and student employability.

The US’s “new political situation . . . [has been] favourable for Hong Kong” and is allowing HKU to “get even better people,” said Heiwai Tang, HKU’s associate vice-president.

“Trump’s new policies that are targeting top universities in the US [are] starting to encourage quite a lot of professors over there to consider outside options,” Tang said, while Hong Kong is also “one of the few places on earth [where] universities can pay salaries that are competitive [and] comparable to the US ones”.

Among the more high-profile moves, neuroscientist Michael Häusser joined HKU in 2024 from UCL in London to become director of the school of biomedical sciences, and political scientist Robert Thomson moved from Australia’s Monash University last year to head HKU’s politics and public administration department.

Beijing’s tighter political grip on Hong Kong and the rising proportion of mainland Chinese academics and students have fuelled critics’ concerns of “mainlandisation” and fears that the territory’s institutions would over time become less independent.

In its latest renewal of the three-year university accountability agreement signed in June, HKU said it would continually support “Hong Kong’s integration into the overall development of [China]” and “strive to follow the advice and guidance of the central government on the future of Hong Kong”.

HKU’s Thomson, who previously also held roles at the University of Strathclyde and Trinity College Dublin, said while Hong Kong’s political system “placed obvious limits on the ways in which academics engage with local politics”, HKU is still appealing as it has “a history, tradition, but also that kind of ambition, hunger that you generally find in newer institutions [to] excel”.

Some academics still “tend to self-censor,” said the HKU social sciences lecturer. “I cannot tell you about all my colleagues, but people that I talk to . . . they will just not discuss sensitive topics.”

“It’s always relative thinking,” said a HKU associate professor who had studied in the US. “It’s not like everywhere is great, but here [is the only place that] is bad. Everywhere is volatile. If anything, here [Hong Kong] is quite stable.”

Hong Kong is an international education centre, as well as an international financial centre, said HKU’s Tang. “If we lose either of the two, Hong Kong is over,” he added.

Additional reporting by Cheng Leng in Hong Kong